Breaking the Cycle, Beating the Cyclones

Whether building a house or educating a kid, climate needs to be considered, says Sankar Halder.

War in Ukraine rages. Markets roil. Inflation has spiked. New waves of Covid gain deadly momentum, especially in China, the country with the world’s largest population and second largest economy. Worries abound.

Still, the need to address global warming remains more urgent than ever, even if tempting to place on a backburner. We still need to push forward with climate solutions, multitasking our way through a plethora of emergencies competing for our attention, many caused in part or worsened by climate change itself. One only need to read the news, albeit now on the inside pages, sidebar scrolls and off-prime-time broadcasts, to be reminded of this urgency.

So I’m forging ahead here with the second of three posts on my visit to the Indian Sundarbans (the first). Here the war in Ukraine seems distant, while the ravages of global warming present immediate challenges each day. Bricks and sandbags accumulate in every village this time of year, as the annual reinforcement of homes and river embankments against cyclones takes place. It’s one of the many practices that once provided a measure of protection against rising waters but are now increasingly found wanting in the face of the more frequent and powerful storms global warming generates.

So far in this newsletter, we’ve visited a tiny, cattle-fueled biogas facility serving a school (this earlier post) and a mangrove restoration initiative by a curious botanist (my last post, as also linked above). Here we look at a community resilience-building initiative started by a village-born kid turned international IT consultant who is now helping back home.

These small efforts may seem insignificant in the face of war in Europe, much less the sheer scale of the climate challenge. Each alone, they are. But small-scale, local initiatives such as these, in aggregate and across the world are just as essential to adapting to global warming and pushing towards solutions as the mega-projects I’ll look at later in the journey.

In a way, the mega-scale undertakings needed to arrest climate change — transitioning away from fossil fuels and overhauling agriculture to eliminate greenhouse gas emissions, to name the most urgent — will happen only on foundations laid by local climate adaptation efforts. They’re what will help communities maintain the wherewithal to take on the big changes ahead.

“This is my home.”

— Sankar Halder.

Few understand change better than inhabitants of the Sundarbans. Theirs is a world of shifting land, tidal surges and furious cyclones. They know how to adapt. Yet today they find it ever harder to keep up with the pace of climate change.

Sankar Halder grew up here, in the tiny village of Purba Shridharpur. As a kid, his smarts caught the attention of a teacher who helped him get into a better school in the city of Kolkata a few hours train ride away. His village pulled together to help his family pay. He eventually joined the budding field of information technology, landed a job at one of India’s top IT consultancies and worked for a decade and a half in the U.S. and Australia. Then he returned to India.

Halder, 48, lives in Kolkata now with his wife and two teenage daughters. But he spends a lot of time back in Purba Shridharpur. There he runs Mukti, a private nonprofit organization aiming to build a kind of community resilience he hopes can stand up to the ravages of climate change even in the Sundarbans, one of the most vulnerable places on the planet. Gradually he’s expanding the approach across the state of West Bengal and beyond.

Born under a thatch roof, educated in a big city, internationalized while working abroad, Halder still says of Purba Shridharpur, “This is my home.”

He’s one of millions of local leaders around the world trying to help their communities become more resilient to the impacts of a rapidly changing climate. Tens if not hundreds of millions more will be necessary. They’re needed not just to help communities adapt to the fallout of global warming. The resilience they foster also bolsters community capacity to take on the often equally disruptive changes required to decarbonize our way of life, whether that’s overhauling agriculture or how we produce and consume energy.

Communities put off those changes if they’re forever trying recover from one crisis and bracing for the next — which is increasingly what life in the Sunderbans looks like. This vicious cycle will characterize life in many more places as the impacts of global warming gain momentum, which they inexorably will until worldwide emissions of greenhouse gases net out at zero.

Mukti, which means “freedom” in Bengali, does many things: provides jobs, makes small loans to entrepreneurial women, promotes sustainable agriculture, and works on health care and sanitation. Its housing initiative epitomizes Halder’s approach.

Imagine a house built not only to stand up, but even more expressly to stay down — anchored to the ground against the strongest winds and rushing floodwaters cyclones can muster. It’s a home, but also a place where a family could shelter during a cyclone. After withstanding a storm, it’s back to being a home again.

Actually, you don’t have to imagine. Here’s what it looks like, one of three prototype houses Mukti is constructing for 100 families in the pilot phase of the initiative…

The homes are a model for more than just housing. They embody a community based, government backed, privately run ethos, paid for mostly with a blend of government and Mukti funds (which largely come from corporate social responsibility funds and charitable contributions). Buyers put up about 20% of the roughly $3,500 cost of a house in cash, and sometimes their own labor.

“We say, ‘We’ll build you a durable, flood-tolerant home. Why don’t you spend some time helping build the community?’” says Halder. “We don’t give anything for free. You have to work for it.”

The homestead initiative even has an element of international cooperation. The houses are designed by Laurent Fournier, a French architect based in Kolkata who has developed a specialization in affordable, cyclone-resistant, flood-tolerant housing.

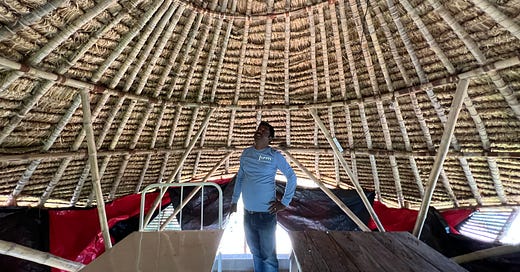

The homes use traditional local materials such as jute plant, bamboo and thatch, combined with some concrete, tin and even chicken wire for added strength. The roof support system is based on the same principles as a Japanese parasol, which stands out in this photo of the upper floor.

Yet if the housing embodies Halder’s vision, education is the key to realizing it, he says. That’s why one of Mukti’s biggest initiatives provides supplementary schooling for more than 6,000 elementary, middle and high school students at 52 locations. Kids chosen for Mukti’s supplemental classes arrive to school at 6 am, three hours before the start of the regular school day, which they then attend, as well.

Supplemental schooling is critical for children who often attend failing public schools with hundreds of students per teacher. But it is one of the first things to go when poor families lose their income, simply because they don’t have other non-essential expenses to cut. This leaves these communities even more vulnerable over the long haul, unable to escape from round after round of repeated disaster. With education, villagers will better grasp the challenges, develop better capability to address them and learns the skills necessary to thrive elsewhere if they’re overwhelmed in the end and have to move.

“Whatever the situation becomes, we have to keep our education up and running. Without that we cannot break this cycle.” says Halder

And climate change?

“Climate and environment cut across it all. Agriculture has to be climate resilient. Your health needs to be. Your livelihood. Your housing,” he told me as we sipped tea on a cool morning in his garden, down the dirt road from Mukti’s main headquarters near the village. “Whatever the economic or development initiative, it has to be climate resilient, especially in this region, or it doesn’t make any sense. We can do many things, but overnight a cyclone can come along and destroy everything.”

Hello Bill, very nice article on the wonderful work of Sankar Haldar and his team and their friends!

Please allow me to add that these 3 prototypes of cyclone-resistant and flood-resistant houses have been designed as 1:1 scale catalog of vernacular techniques from the Sundarbans and from various parts of India, from Bhuj to Kerala to Uttar Pradesh, all put together by a team of at least 4 architects and 2 draftsmen and several students, coordinated by Kolkata-based designer, Sangita Kapoor.

Taken together, these 3 houses showcase 3 types of wall, 3 types of vertical structure, 3 types of foundations, 3 types of doors and windows, 3 types of horizontal structure (floor), 3 types of flooring, 3 types of staircases, 3 types of roofing structure, and 4 types of roofing materials, some of them very ancient, some others invented less than 20 years ago, all selected for their affordability, strength, comfort and use of local materials and skills. Such a diversity would certainly not have been achievable by one single person, and the harmonious and consistent combination of all these techniques owes a lot to the skill and experience of Sangita Kapoor.

- Laurent Fournier