Two Hundred Cows, Two Tons of Manure, Two Thousand Cooked Meals….All in a School Day.

A tiny biogas facility outside of Mumbai is a good place to start an adventure looking at India’s energy transition and what it means for the world.

This week, the world’s top group of scientists examining climate change dropped a colossal compendium of the impacts that global warming is already having on the planet. The official summary of the report runs nearly 100 pages, with the full report weighing in at around ten times that. There’s a lot of climate impact already underway. The report meticulously, scientifically works its way through all of them, touching on nearly every corner of the earth.

But the key point isn’t that the damage is already occuring, or that it is already eye-openingly extensive. It’s that there is much we can do. We can, indeed must, immediately and drastically accelerate efforts to reduce the amount of global warming gasses we’re spewing into the atmosphere. We need to drive the balance of what we emit verses what we remove from the atmosphere to zero by mid-century. We can, indeed are already having to, adapt to a warmer world — one with the more intense storms, rising risk of fires, substantially higher temperatures and far more frequent droughts and floods. We must adapt — skillfully, cleverly and in a way that’s fair and just — not only to mitigate damage and maintain healthy societies for their own sake. We must do it in order to maintain the wherewithal to take on the greatest challenge humans have faced to date: transitioning our way of living from carbon intensive to carbon free at what amounts to warp speed.

We’ve examined and analyzed many of these issues in this newsletter, focusing on India (here’s why). The journey now takes to India itself for the coming months. The global climate report this week — the second of three by the group — is as mammoth as the challenges ahead. But that doesn’t mean they’re insurmountable…..

So we’re going to start small. And since it’s India, with a cow.

Or, actually, 200 cows.

This is the cattle barn at the Ram Ratna Vidya Mandir school in the district of Mira Bhayandar, along India’s Arabian seacoast. It’s an hour’s drive north of central Mumbai (once known as Bombay).

The herd is owned and managed by a civil society group to provide milk and other dairy for a school and various community organizations the group runs. But for the past eight years, the cows have another job: helping create methane fuel to cook several thousand meals a day for the students and staff.

On its own, the biogas project is tiny. Overseen by another, energy focused civil society group called Gram Oorja — which loosely translated means Energy for the Village — the facility turns cow dung into cooking gas. End products also include a manure slurry that’s used as fertilizer on nearby fields to grow mango, coconuts and other produce for the school. Presto, the byproduct of gas production is used to grow some of the food that’s ultimately cooked with the gas.

Started by a trio of former bankers in the late 2000s, Gram Oorja has overseen 377 projects in 28 districts covering 100,000 Indians. These include solar powered irrigation pumps and small solar energy systems, known as microgrids, that provide electricity to villages located far off the public power grid. Funding generally comes from companies that either want to test concepts for new business lines or make philanthropic contributions under India’s corporate responsibility requirements.

Here’s why it matters in a bigger way, though: First off, while Gram Oorja’s project here is tiny, India’s cattle population is not. It’s the largest of any country, some 305 million cows and water buffalo as of 2021. There’s plenty of potential for projects like this to expand dramatically. Then there’s the recycling and re-use practiced at the Ram Ratna school project. They may seem like something out of a hippie commune, but here it’s mostly just practical. This mindset of recycling and re-use is working its way into new thinking about the global economy as the world bears down on the task of decarbonizing. It’s often referred to as the “circular economy.” But this is really just practical thinking for a new era that’s beginning in energy and agriculture, in India and beyond. This thinking is being taken up by some very big companies and industries, not just villages.

These concepts are being scaled up — and will eventually have to continue scaling up exponentially, almost unimaginably — until they rival the scale of the fossil fuel-based production and consumption machine we understand as our economy.

These include new ways to recycle innumerable megatons worth of the elements that go into batteries, which will be at the heart of both our transportation systems and our power grids. Effective re- and mult- use will be the key to solar power facilities that will produce drinking water from the sea and transform fresh water into hydrogen that can provide the heat to make “green” steel or propel airplanes. Even carbon removed from the atmosphere can be locked up by forging it into useful materials. The additional energy India will need to develop will increasingly need to come from renewable sources, small ones like the biogas facility here but also extremely large ones that apply some of the same principles.

What’s perhaps the most important of those principles?

Ask Bishan Das Agnihotri what the 70-year-old former Indian sailor, who has managed the Ramratna complex for 18 years, likes about the system and he doesn’t talk first about saving the planet. Before anything else, he cites cost savings.

“High pressure gas is expensive,” he says of the tanks of Liquid Petroleum Gas, or LPG, that are his next best alternative.

He figures the school saves about 2,000 rupees, or about $27 a day, by cutting the number of LPG cylinders they use each day by a little more than half, enough savings to feed dozens of students.

“That’s very good,” he says, beaming.

So while the biogas project here at Ram Ratna school is small, it’s worth understanding. And thinking about.

Sameer Nair, a Gram Oorja founder, gave us a tour of the project, and here’s now the system works:

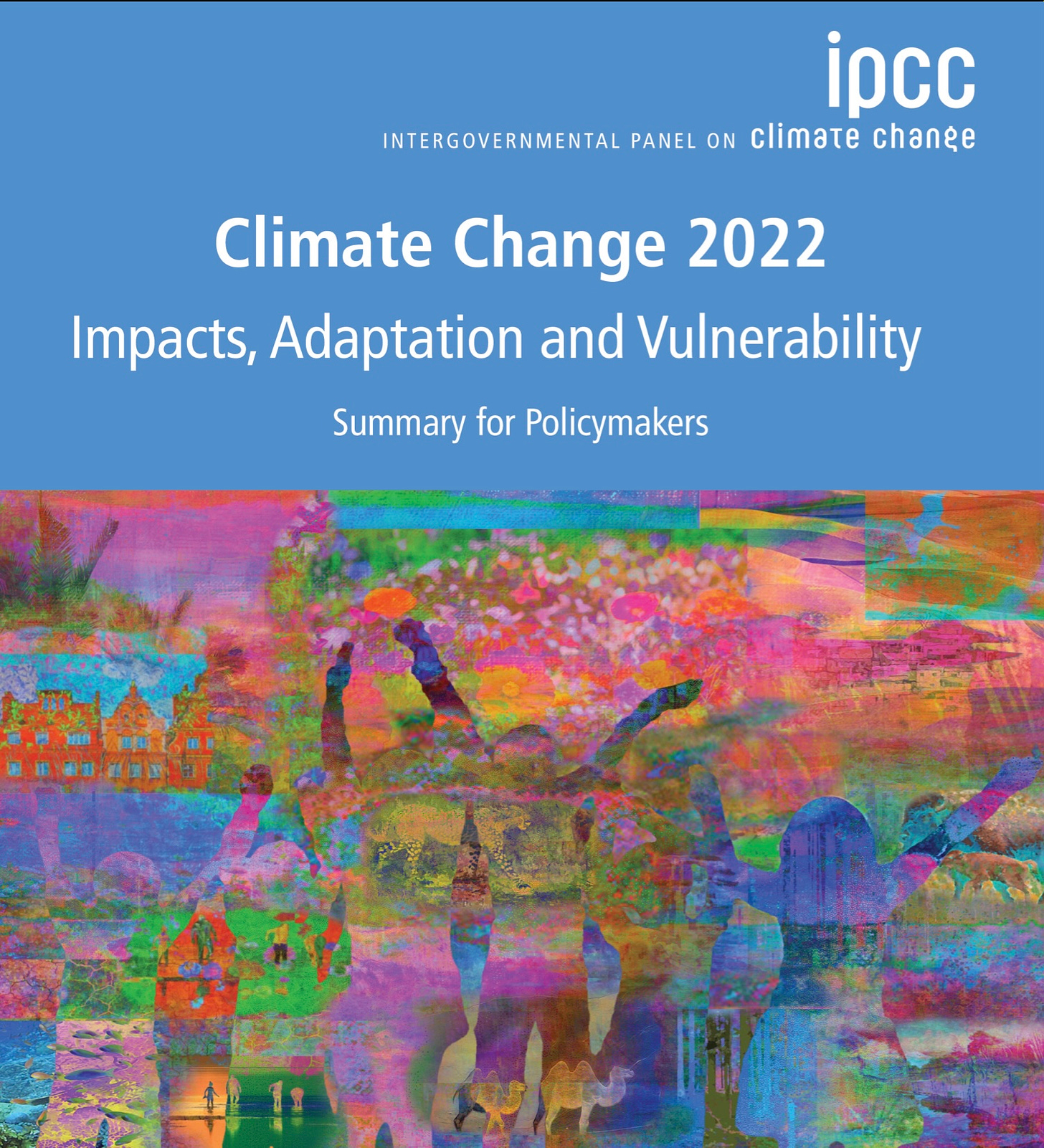

You’ve seen the cows. The 8,000 or so pounds of, shall we say, byproduct they produce each day is put into the gas-producing “digester” along with any human or cattle food leftovers. The leftovers are even better than the manure, though there’s a lot less of it. The undigested food will produce higher energy gas, since it hasn’t been, well, digested. That’s Rahul Karekar, the 36-year-old Gram Oorja employee who manages the group’s biogas projects, standing with it.

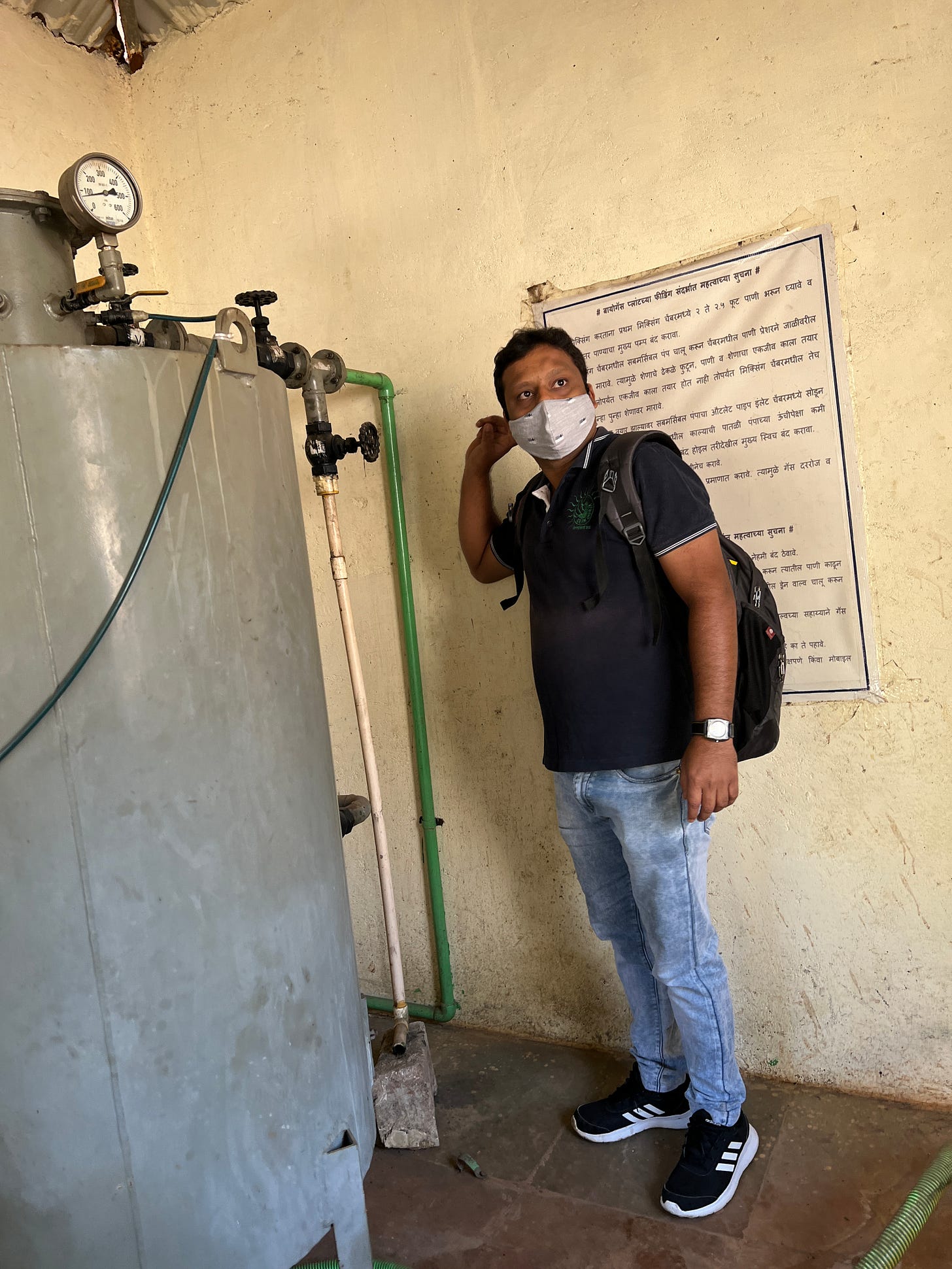

Inside the digester, an underground concrete cylinder with a loose canvas cover, bacteria go to work doing their thing, producing gas in the process. That inflates dome on top of the digester like a balloon. Here’s what it looks like, decorated with what’s known as Warli painting by tribal groups from the area and whose children attend the school….

Before the gas can be used, smelly and poisonous hydrogen sulfide has to be “scrubbed out”. That’s what this machine does…..

Here’s the slurry that’s left at the end and used as fertilizer. It’s remarkably un-smelly (the masks are for Covid protection)…

From there the methane gas is ready for use. With the help of a blower, it’s piped down the road, along which there are some pretty views of the lush valley in Maharashtra state.

…until it reaches the school…

…and on into the kitchen…

…where it works just like the LPG, though with somewhat less heat per unit of gas. For boiling water it’s great, a little less so for deep frying, says cook Om Prakesh, who’s 54 and worked at the school for a year.

And, when the food is done, on to the canteen for the students when they arrive…

For the more technically curious, here’s a schematic showing the whole process…