In the Sprawl of the Sundarbans, Climate Change is a Harbinger of What is to Come

Mangroves offer a critical opportunity to break a vicious cycle between humans and their habitat…

Hemendra Kotal, graduate student in botany:

“But regular people, they have to understand first what we are doing, what is the noble reason for these plantations to protect the mangroves.”

— On a boat in the Indian Sundarbans.

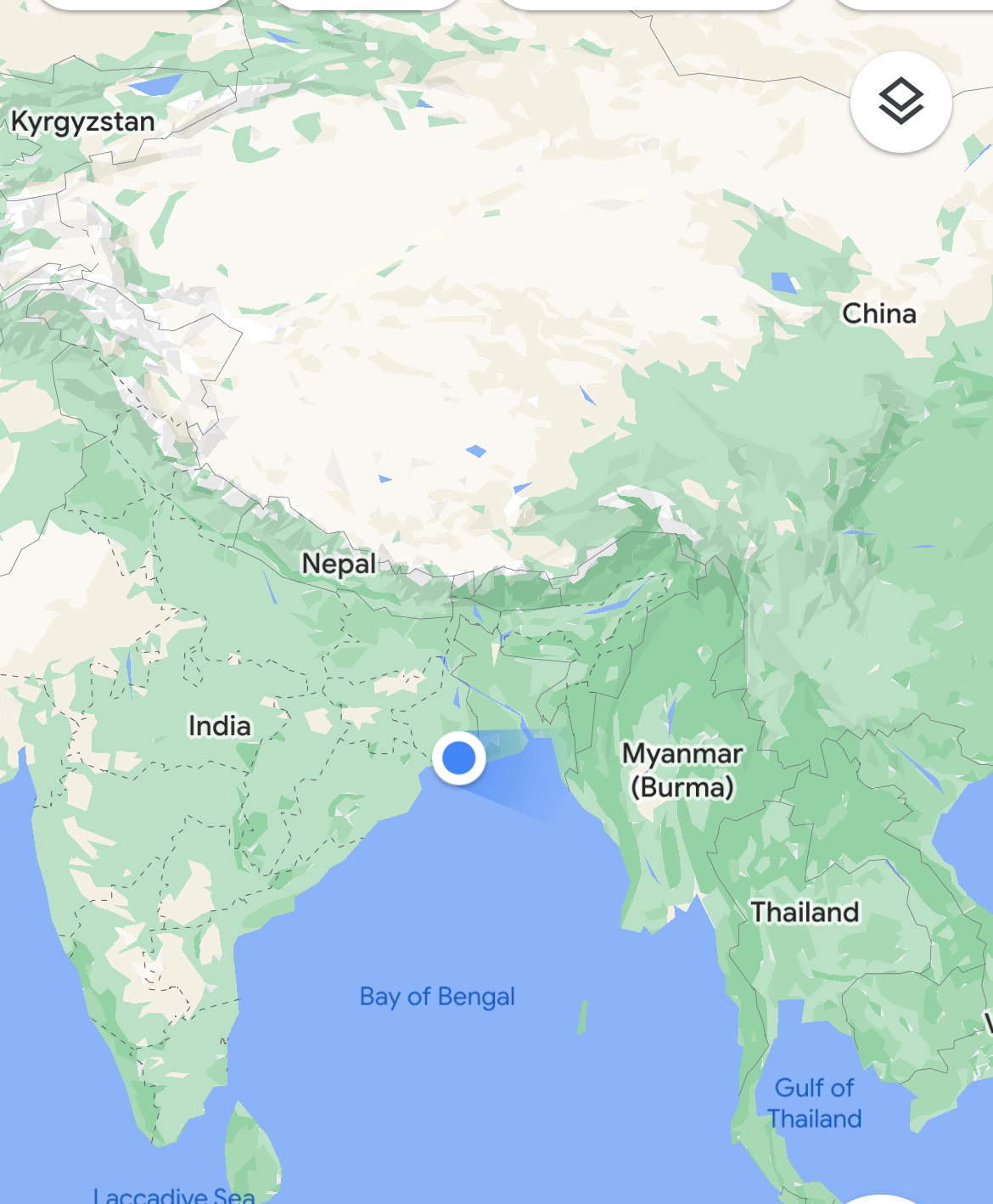

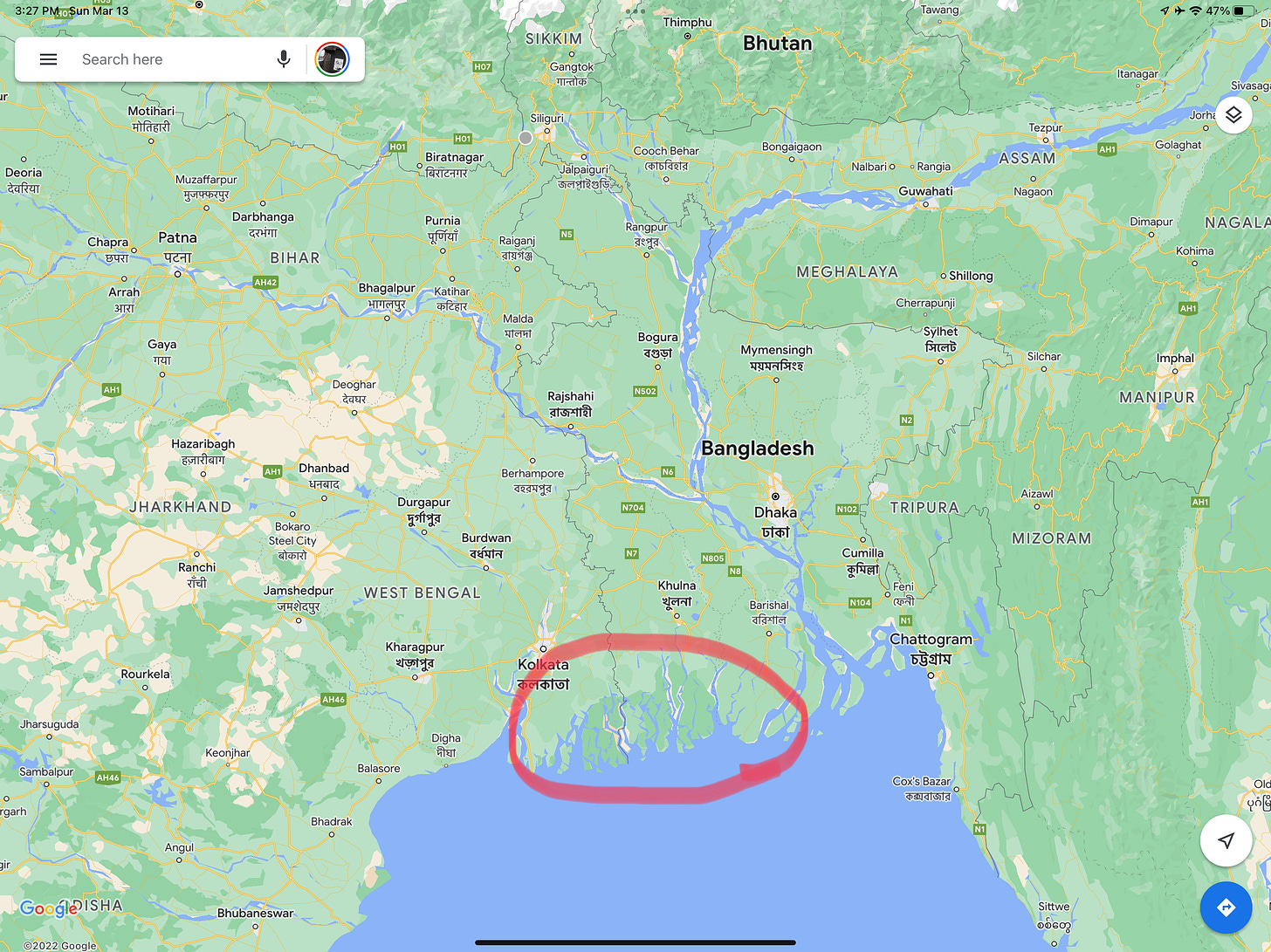

The Sundarbans — the “beautiful forest” — sprawl into a delta where three legendary rivers of South Asia meet the Bay of Bengal. It is the largest and most complex mangrove ecosystem in the world, a tidal estuary half again larger than Florida’s Everglades.

But the Sundarbans are in deep trouble.

Dr. Krishna Ray and a determined team of young botanists she oversees are trying to rescue them. That’s not easy when surprisingly little is understood about precisely how these complicated swamps grow and thrive. Dr. Ray and her team are discovering what makes them tick. Hemendra Kotal, Chayan Giri and Anup Mandal are part of the team. All three grew up in West Bengal, the Indian state where the Sundarbans are located.

Still, they come from distinctly different backgrounds. Anup grew up in a town where the Himalayan hills in the state’s north begin to give way to the alluvial plain that defines its south. Hemendra is from the mega-city of Kolkata, once British India’s colonial capital, upstream from the Sundarbans. Chayan was born and raised in the Sunderbans themselves, on the largest island among more than 100, facing the Bay of Bengal. They are in their mid-twenties, pursuing doctoral studies. Two other members of the team — Ranjan Pradhan and Subhra Kanti Tripathy — are locals from the village of Ramganga who help with the work.

I tagged along with the group as they traveled the winding waterways by boat gathering samples of soil, water and the many varieties of mangrove plants. They pored over everything from the precise composition of plant species in each patch of mangrove they are restoring — Ceriops decandra versus Aegialitis rotundifolia, Xylocarpus mekongensis compared to Bruguiera gymnorrhiza— to the array of microbial bacteria inhabiting the soil deep below the surface. Dr. Ray toggled effortlessly on deck between encouraging her team of Ph.D. candidates and cajoling her project funders in the Indian government by mobile phone.

As distant as this meandering amalgam of islands and waterways can seem — even for many Indians and neighboring Bangladeshis, whose country takes in more than half of the delta — the region matters globally. Mangroves are impressive carbon storehouses, locking up millions of tons of the stuff both above and below ground. Like tropical rainforests, they are super-dense, intricate agglomerations of plants and animals — from legions of bacteria and armies of insects to the last 250 or so wild Royal Bengal tigers — so big their destruction would be felt far beyond their actual borders.

Mangrove roots plunge deep into the waterlogged soil — a mix of clay, sand and silt — holding it in place against powerful tidal ebbs and flows twice each day. Those same roots also rise back up from the soil surface in knobby protrusions the plants literally breathe through. Robust mangrove stands can buffer the increasingly intense cyclones that batter these shores beginning late spring and running through to the fall. They are also critical to managing the inexorable rise of the sea level itself, one of several climate change impacts wreaking havoc across the fragile ecosystem.

Healthy mangroves function as a protective barrier for life above the waterline. This includes the more than four million Indians and three million Bangladeshis who inhabit this tenuous landscape. The area was very sparsely populated before the British colonial government began encouraging migration here in hopes of expanding its tax base and obtaining new forest resources to export.

Population growth has exploded in the past half-century. Yet apart from some tourism, fishing, logging and honey gathering, there’s virtually no large-scale economic activity. Everyone here suffers burdens of accelerating climate change, but they are falling most heavily on women, who are responsible for finding potable water and much of the work in rice paddies and fields, both increasingly difficult tasks.

Distant as all this may seem, their struggles with climate change will become increasingly familiar to people everywhere. Their world is changing fast now, much faster than they have the resources or wherewithal to adapt to. They’re losing ground, in small but steady increments tide after tide, in larger chunks cyclone by cyclone. Four large storms have slammed into the area in the past three years, leaving scars across the interwoven land and seascape and its inhabitants reeling, humans and microbes alike.

This is the first of three dispatches on my visit to the Sundarbans.

Regular readers will notice they are the first I’m focusing squarely on climate change impact, rather than energy transition. That’s been a deficiency of this space, since they’re really two sides of the same coin. The solutions to global warming — energy transition, restructuring our agricultural system, rethinking how we build things and live our lives — will only be possible if we also manage our way through the tumult caused by climate change itself in ways that maintain a modicum of stability. This will require resilience. So it’s worth a look at some communities, however removed from our own experience, fully in the throes of trying to develop this sort of resilience.

They are harbingers of the profound challenges careening toward the rest of the world as global warming gains momentum. The longer we wait to eliminate the greenhouse gas emissions causing the climate to warm, the more our future will resemble their struggle to keep up with a rapidly changing world.

The residents of the Sundarbans did nothing to cause climate change. Most didn’t even have electricity until a decade or so ago. Some still don’t. A miniscule few own cars. Yet if climate change is threatening to overwhelm the Sunderbans, humans are nonetheless doing plenty to help it. They dam and divert the rivers that spill down from the Himalayas and across the plains, diminishing the flow of fresh water from the north into the swampy delta. Meanwhile they build ever higher berms and embankments on the Bay of Bengal to the south to try to keep the sea off the land, especially during storms. The embankments displace mangroves, often through misguidedly uprooting them during construction.

The combination is a deadly challenge to complex mangrove ecosystems, which are what they are in part due to wide gradations in water and soil salinity. It’s the worst of both worlds for them, with humans literally uprooting them from one side and denying them the brackish water by blocking the fresh water flow from the rivers on the other.

The result is a vicious cycle: degrading mangroves leave islands more exposed to rising sea levels and more frequent and forceful storms; that spurs construction of more embankments, which makes it harder for mangroves to regain a foothold. The West Bengal state government now requires 50 meters of shoreline in front of embankments, but in practice the barriers usually wind up being built right at the water’s edge or the land in front of them erodes away. The result is mile upon mile of embankments lining river banks denuded of mangrove.

“We may lose half of the Sundarban mangrove forest area by 2100 unless we do something about it,” says Sugata Hazira, an oceanographer who has studied the Sundarbans extensively and is not involved in Dr. Ray’s research. “We have to protect the protector.”

This is the cycle Dr. Ray and her teams are seeking to break — by figuring out how to help the mangroves grow back.

It turns out to be harder than just re-planting. They’re puzzling out why, finding ways to turn barren stretches of river bank back into robust mangrove habitat. My trip with them was one of dozens they make each year.

A key, they have found, is grasses. Grasses are found only sparsely in fully developed mangrove stands. But Dr. Ray and her team have discovered they play a critical role in helping mangroves gain new footholds where they have lost their grip on the shifting mud flats. Once grasses are established, the mangrove seedlings nestle into the grassy tangle. There they can grow, protected from being washed away in the intense, twice-daily tidal currents.

So Dr. Ray and her team start not with the mangroves, but rather more humbly — with the grasses. Where it works, this breaks the vicious cycle. Grasses give way to the growth of various mangroves that like the salty sea water at the shoreline. As silt and sand builds around those, nurturing them further, the salinity levels in the soil drop and other, less-salt water loving, mangrove species take hold. Eventually the collective habitat begins to resemble the robust stands that existed before, and still survive in less populated, more protected parts of the Sunderbans.

In total, the 31 plots her team is restoring add up to less than a quarter of a mile square, scattered about the inhabited parts of a wetland that covers 3,800 square miles. She hopes to expand to many more sites as they refine their work

This will take years, if not decades, and lots of replanting and nurturing by Dr. Ray’s team and local villagers they enlist in the effort. Some parts may never grow back the same. Ray and her team have been trying to reestablish a species of mangrove known as Sundari — a variety once so dominant that some believe it’s where the name of the region comes from. Sundari have very little salt tolerance, so struggle to grow in the saltier soils that now dominate the Sundarbans.

“We planted more than six thousand seedlings, but we failed,” says Dr. Ray, undeterred. “Now with the monsoon rains the salinity of the soil has dropped and we’ll try again.”

Where they have had success, the end result is a village protected by an embankment that is shielded by a buffer of mangroves. The combination, where it exists, has stood up against even the strongest storms so far. From there the mangroves can grow and spread, as they have here for thousands of years.

“Where we plant and what we plant is important. We have to study them first,” says Anup. “A forest can only be defined by multiple species.”

At the end of our four-day journey through the Sundarbans, Dr. Ray and her team puzzled over something they noticed: a particular bacteria exists in far lower concentrations in pristine areas of the wetland where they have taken samples, compared to the areas they have under restoration.

Indeed, the more developed the restoration, the lower the concentration is of this particular microbe in the soil.

“We’re looking closely at this,” Dr. Ray asks her team. “Why is this?”