As 2024 wrapped up, reality set in.

Climate policy means real trade offs. We’ll need to get the balance right.

As 2024 closes, I wanted to note just how momentous the past 12 months have been for the world’s approach to addressing climate change.

While it’s too much to dub the past 12 months “the year we gave up,” it’s certainly been a year of reckoning. Realities set in, in ways they hadn’t before. For better or worse, we’ve come to see what sort of a “crisis” we face and the shoals our current strategy for dealing with it are running up on.

A choice is now upon us. Which way from here? Towards full-blown surrender to global warming in favor of energy security, narrowly defined, and the economics of short-term thinking? Or a reformulation of our approach, whatever that might be, that pursues security, broadly defined, and economic prosperity for the long run.

The Energy Adventure(r)’s 2024 travels have been extensive, thanks to support from Cipher News and a generous grant from the The Alicia Patterson Foundation. I’ve shared some of those adventures already: Australia here, here, here and here; Singapore here and here. The Philippines here and here; I’ll soon be sharing recent adventures in Argentina and Chile — think glaciers, green hydrogen and the geopolitics of mining!

In this post I wanted to reflect on my two lengthly visits to Japan this year. Among the eight countries the Energy Adventure(r) visited, Japan is where I spent the most time. I speak Japanese, having lived and reported there for most of the 1990s. It’s a place I love and know, though I’m always learning new things.

You can read my stories for Cipher this year about Japan’s evolving energy strategy and bet on hydrogen (here and here), its nuclear plans (here) and carbon capture (here). I’ve written about Japan’s efforts to develop offshore wind power (here and here) and Japan’s lagging decarbonization efforts (here).

The country’s ambivalent, halting, disappointing-to-many yet nonetheless muddling-forward energy transition says a lot about where the world finds itself with climate and energy transition right now.

During my most recent visit to Tokyo, I met Vaclav Smil, the influential energy-and-society guru whose pessimism (he calls it realism) about the world transitioning away from fossil fuels is famous, or infamous, depending on who you ask. In a conference presentation, he summed up his view of the world’s pursuit of net zero carbon emissions by 2050 in four words: “Not going to happen.”

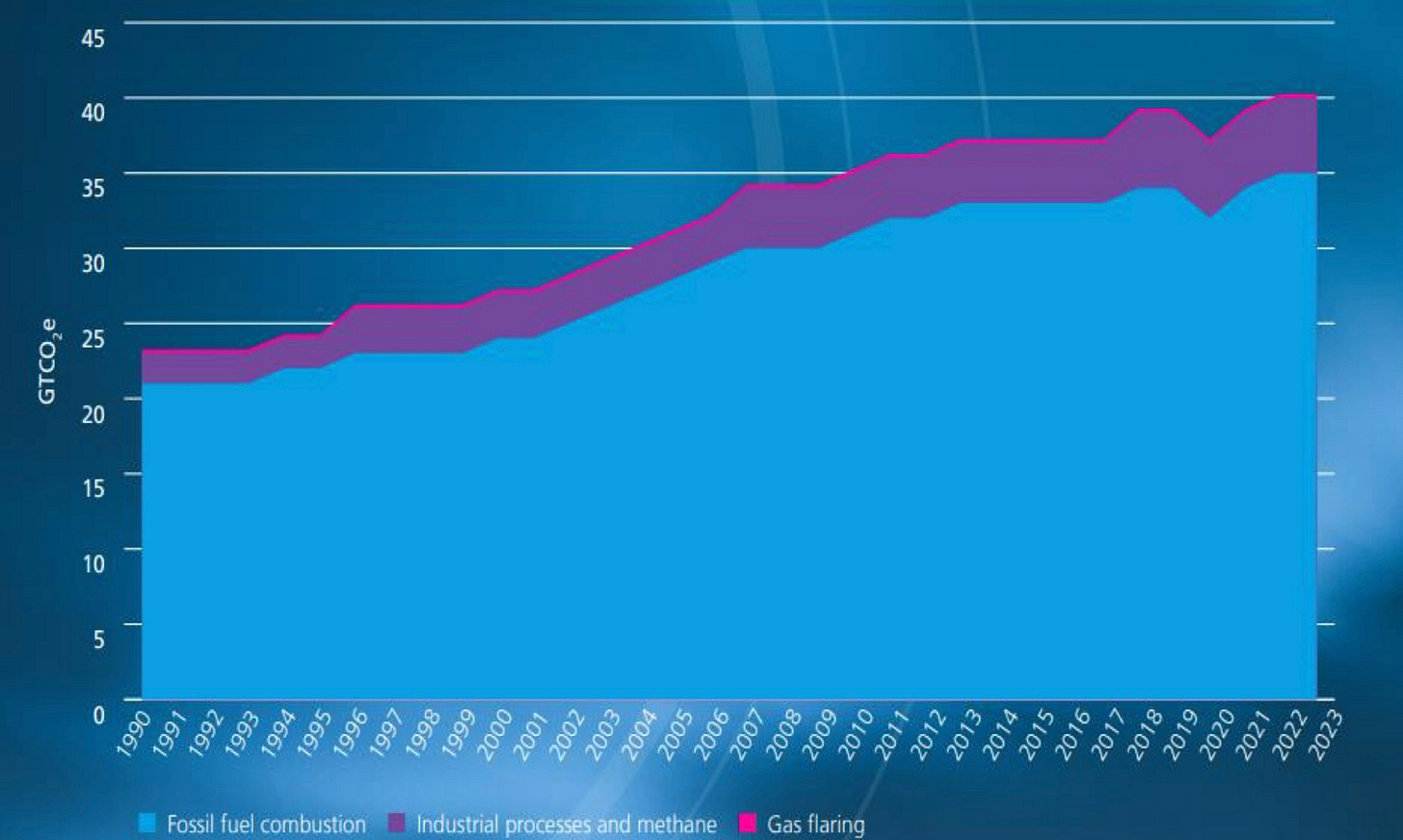

He argues this is not for lack of clean energy technology or the money to deploy it. In a world of rising energy demand, the mission impossible as he sees it is deploying those two things — technology and money — quickly enough to replace fossil-fuels while still keeping up with growing demand for energy, especially in the developing world. Historically, wholesale energy transitions like that take centuries, if they happen at all. Sometimes new forms of energy just gain traction alongside the old ones, which grow too, just more slowly to take on a smaller role in an overall larger energy system. More coal, for example, got burned in 2024 than ever before despite the meteoric rise in clean energy, especially solar power, over the last decade.

“The main problem is scale,” Smil says.

The fossil-fuel based system is simply too big to upend — maybe ever. Or so his logic goes. Right or wrong, candidates who embrace this sort of logic dominated elections around the world, which among other results returned a climate denier to the White House along with a coterie of fossil fuel advocates on his coattails. That was followed immediately by COP29, the global climate confab, which retreated from any mention of fossil fuels being problematic, the conference’s main takeaway just a year earlier.

But another reality set in during 2024. The earth, yet again, heated to new all-time highs. For the first time, the average global temperature exceeded the 1.5 degree Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) of warming above the pre-industrial average the world was officially hoping to avoid. Beyond that level, the impacts of climate change — stronger storms, deeper droughts, longer heat waves, the sorts of things we saw a lot of in 2024 — really begin to accelerate. Research on the nature of climate change, which advanced significantly in 2024, is beginning to hint that once this acceleration gains enough steam, the fallout isn’t reversible and could even gain momentum.

Even many fossil-fuel advocates now acknowledge that greenhouse gas emissions are causing global warming, creating fallout that will intensify with further emissions.

Of course among climate activists, who long recognized this, alarm has only grown. They underscore, correctly, that the cost of removing excess greenhouse gases from the atmosphere — or dealing with the fallout while nature does the job over centuries — will over the fullness of time be vastly higher than avoiding those emissions in the first place.

But 2024 was full of reminders that in the short term — the quarterly view of a publicly traded company, the annual budget of a country, the paycheck of a consumer or the election cycle of a politician — the cost to decarbonize the energy system as soon as physically possible is almost always higher.

There is, in other words, no magic solution to the Smil’s scaling challenge — even in the face of a spiraling climate problem. This late in the decarbonization game, trade-offs are unavoidable. That’s the place we find ourselves at the end of 2024.

Responses to this predicament vary.

The returning President Trump remains a climate denier — albeit in an unconvincing, I-can’t-be-bothered sort of way. Some of his fossil-fuel advocating energy strategists and cabinet picks acknowledge climate change and the role fossil fuels play in causing it. Oil and gas companies work to turn the focus from fossil fuels back towards the emissions, which they increasingly admit are a problem.

Yet there’s no climate “crisis,” they argue. Those advocating ditching fossil fuels, now or ever, are alarmist or elitist. There’s energy security to be considered, energy demand to be met and money to be made — artificial intelligence-crunching data centers to be built, factories to stand up, air conditioners to be run, smartphones to charge, airplanes and ships to be fueled. This is the stuff of modern life the developed world has long enjoyed and the developing world deserves to enjoy, too. What’s a climate problem to get in the way of all that, even one that disproportionately clobbers the world’s poor and most vulnerable?

For their part, climate activists and leaders of the most vulnerable countries have grown even more alarmed and shrill, which is understandable but unproductive when they’re no longer pushing on an open door.

That’s where I find a bit of hope in Japan, even amidst its generally dubious embrace of clean hydrogen as a catch-all decarbonization plan. A future where clean hydrogen solves all energy problems has long been a collective Japan Inc. dream — at least since the days I roamed the halls of the economy and trade ministry when I covered Toyota, one of the biggest hydrogen dreamers, in the early 1990s.

Hydrogen — as I explain in this Cipher story — is Japan’s attempt to work around Smil’s scaling dilemma, to decarbonize without abandoning trillions of yen of investment in fossil fuel infrastructure. That likely won’t work out as planned.

But will Japan simply abandon recently announced plans to cut emissions, as unrealistic as they may seem and unlikely as they are to be met, as the Trump administration is likely to do? That seems unlikely, too.

There are powerful reasons why the country won’t give up on weaning itself from fossil fuels if its clean hydrogen bet fails.

If few among Japans’ leadership are convinced the country can get off oil, gas and coal for many decades to come, the country’s leadership has never been ideologically or economically tied to fossil fuels in the way oil and gas producers Saudi Arabia and the United States are. Japan has to import all of its fossil fuels — at great expense, always susceptible to the gyrations of global markets and machinations of geopolitics.

Tech giants such as Microsoft, Google and Amazon and their suppliers — all critical to Japan’s economic fortunes and geopolitical security — are on the hunt for carbon-free energy in Japan, as they are everywhere.

And finally, there’s genuine concern about climate change, which Japanese leaders have never really dismissed or downplayed. The first legally binding international treaty to reduce greenhouse gases was forged in Kyoto.

As for clean alternatives, nuclear power is regaining traction in Japan, as it is elsewhere in the world. Japan’s solar plans so far don’t include much potential rooftop space and under-utilized land, a common issue globally. Offshore wind, slated for significant expansion close to shore, may get big boost if floating turbines can be affordably built further offshore. That would be a game-changer everywhere. Geothermal energy is potentially huge for Japan, as it is for many other places.

Those alternatives won’t eliminate Vaclav Smil’s scaling dilemma, since they don’t repurpose existing power generation cost-free. But the alternatives to fossil fuels are proliferating — another reality that couldn’t be ignored this year.

Today is Ōmisoka, New Year’s Eve in Japanese, when they typically greet each other with “Yoi o toshi o…”.

That literally means, “please welcome the new year.” But because the expression is used only until the stroke of midnight, it carries a sense of sending off the current year and all it has brought.

From midnight, they switch to a different expression, a full-throated welcoming of the New Year and all its possibilities. As I finish this post, I note that 2025 has just arrived in Japan. So here it comes:

“Akemashite omeditou goziamas!”

Happy New Year.

Now if I could just find a nice warm bowl of Toshikoshi soba, New Year’s noodles.

Absolutely. Thanks for outpointing. There’s much of interest from the ICEF conference, including the well-worth-watching response to Smil by Rystad Energy CEO Jarand Rystad, later in the same session I linked to.

Thank you for this post, Bill. As always, you beautifully describe the big picture of Japan's approach to the energy transition.