Neville Michael, a 67-year-old seventh generation farmer in rural South Australia, and mega-billionaire Elon Musk don’t have a lot in common.

Except this: Both helped set the state of South Australia on a course that today sees about three-quarters of the state’s electricity coming from renewable energy.

That’s an extraordinary share of energy to come from renewables, far more than many renewable energy skeptics once warned would be possible to manage. Wind and solar together only make up about 12% of power generation globally.

The state, which officially declared climate change a global emergency two years ago, aims to get to 100% renewables no later than 2030.

You can read more about South Australia’s renewable ambitions in this recent article I wrote for Cipher.

The article mentions both Michael (who I met) and Musk (who I didn’t). Their pioneering ways are worth dwelling on a bit more here. Each of their moves reflected their personal circumstances and personalities. Michael’s decision to sign up for wind turbines on his property was a humble one, born of luck and personal necessity. Musk’s impulsive bet to build the world’s largest battery was the opposite — bold and brash, the product of an overactive ego and knack for spinning publicity into profits.

Both moves, both men, both styles, are just what the energy transition needs, and what makes it such an adventure.

It was nearly 200 years ago that Michael’s Scottish ancestors arrived on this plain between two ranges of hills, the Burunga and Hummock, in the mid-north of what is now South Australia.

The land is fertile but has always been subject to the elements, particularly some of the strongest and steadiest winds in the world.

In the late 1990s, Michael had hit hard times.

He told me this over scones and coffee after I made the three hour drive up from Kangaroo Island, spent the night in nearby Snowtown and navigated dirt roads flanked by giant wind turbines to reach his home on a gentle rise in the land.

First, prices for sheep and wool had collapsed. Then the prices for the lentils and barley they grew, as well. Interest rates rose, sending Michael’s variable rate mortgage into the stratosphere. He sold off some of the most valuable land, keeping the ridge line, where it was pretty much impossible to grow anything and thus unsaleable.

One day a letter arrived from a company called Wind Prospects. In the confusion of the times, Michael barely bothered to read it — until a second letter arrived a few months later.

It started out, “Don’t throw this one in the bin,” Michael said.

The letter explained that Wind Prospects wanted to pay him for first rights to place wind turbines on his ridge line, the last place on his property Michael had figured there’d be any value.

They offered him $5,000 a year for the option.

“I didn’t have five cents, so $5,000 a year sounded like a fortune to me,” said Michael.

It took another decade before the giant wind turbines were actually built and spinning on the hillside. Today there are 16 turbines on his property, part of a larger project erected some 100 turbines along about 20 miles of ridge in the area between 2008-2015.

High voltage cables transmit the electricity they generate to the coastal areas where South Australia’s population and industrial centers are located. Michael gets a cut of the revenues from the electricity that the turbines on his farm generate.

Musk’s move happened not long afterwards.

A 2016 storm, the worst South Australia had seen in a half century, knocked over 22 pylons supporting high-voltage power lines that carried electricity across the state. The disruption forced authorities to shut down the entire state’s power. Some opponents of renewables predictably blamed the blackout on renewables.

Of course, the substantial amounts of wind power — and increasingly solar — were not to blame any more than the natural gas or one remaining coal power plant whose electricity delivery was also disrupted. But the blackout underscored the urgent need to assure the grid did hold up as more and more inexpensive wind and solar — both variable sources of energy that aren’t always on — replaced more costly but most always ready for delivery fossil fuels.

Grid managers especially worried about meeting demand during sharp summer peaks.

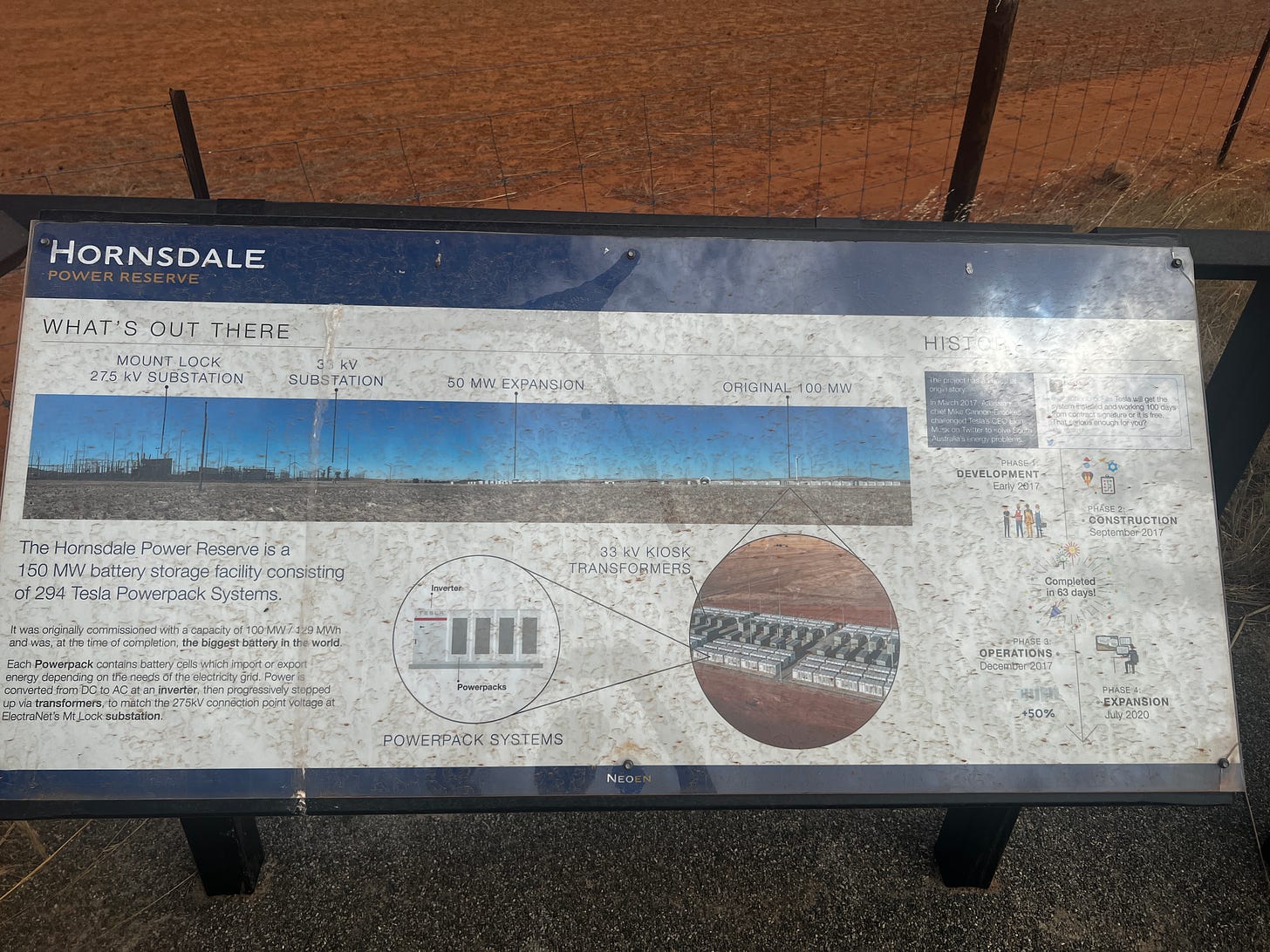

As it happens, this was right around the time a new technology — grid scale batteries — were coming to market for the first time at scale. And that’s where Musk came in. He seems, as usual, to have been attracted to the controversy and business opportunity in equal parts. And as it happened, he had a company, Tesla, that could put much of this problem to bed by building what back then would be the world’s largest lithium-ion battery.

I was unable to share scones, coffee and conversation with Musk. But fortunately, inevitably, his bit played out almost entirely in public.

An Australian billionaire noticed Musk’s boast and challenged him on what was then Twitter: If the money could be arranged, “How serious are you about this?” Mike Cannon-Brookes asked.

Must vowed to build the 100 megawatt battery in 100 days, or pay for it himself.

“That serious enough for you?” he tweeted back.

Musk’s company had the battery up and running in 60 days, making global headlines, at least among the energy transition crowd.

Two years later, the battery was saving the state more than $100 million annually. Since then its capacity has been boosted by half again to save even more. Even larger batteries are going up elsewhere in Australia now, part of a global surge in large-scale batteries for grids.

From Michael’s farm, I was about to drive out and have a look at the famous battery when Tom Michael, Neville’s grown son, arrived at the back door and joined us for a coffee.

While the nearby community is still looking for ways to benefit more broadly from the renewable energy projects in the area, Tom was wondrous of the change that has blown in with the wind in just two decades.

“It’s been just revolutionary to take what’s basically the poorest land in the mid-north and turn it into the most valuable,” said Tom.