As cities grow and waters rise…

A Gold Coast institute looks for opportunity amid the challenges.

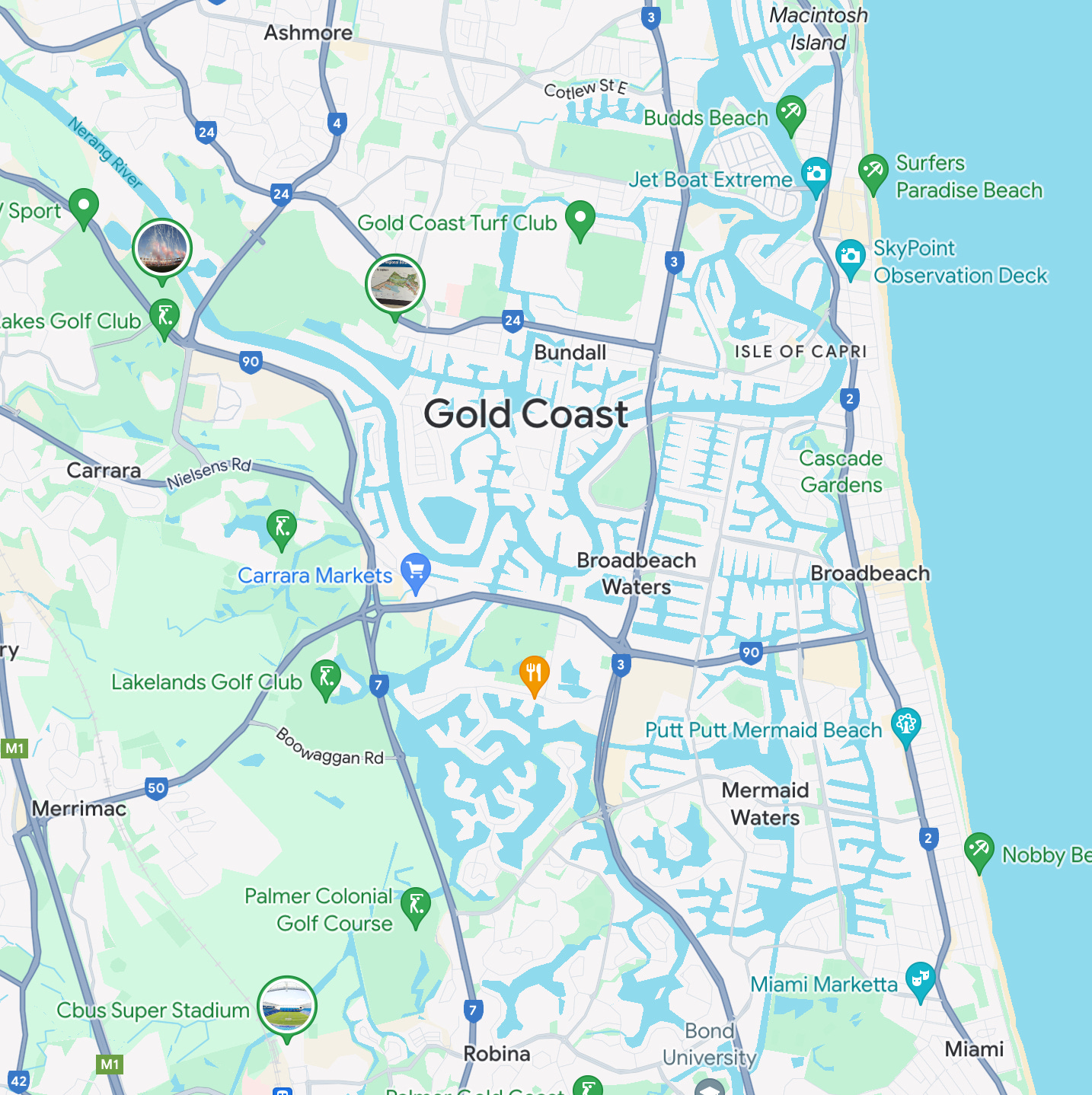

Joerg Baumeister lives in Gold Coast, a city where land and water intermingle by design and intervention. More canals and waterways here than Venice, residents of the Australian city like to point out.

Joerg also founded a research institute devoted to exploring the frontiers of this deliberate intertwining of people, place and water — here along Australia’s east coast and beyond.

All this puts Joerg, Gold Coast and the SeaCities Lab at Griffith University on the cutting edge of perhaps the most inexorable impact of climate change: sea level rise.

I stopped for several days to have a look at the institute’s work and meet Joerg and his partner, Daniela Ottmann, who does amazing sustainability work of her own as professor of architecture and design at nearby Bond University.

In this post I’m focusing on the looming disaster I’ve looked at before in India — here in the Sundarbans and here in Chennai.

It’s hard to overstate: Humanity is on a collision course with the oceans. The water is rising towards us at the same time as we are moving towards it.

Humanity is congregating ever more in cities, especially in the developing world, as young people stream out of rural communities into urban centers. Often these cities lie along coastlines.

Many are growing so fast that the fresh water being pulled from below ground for drinking combined with the weight of buildings being erected above ground are causing the cities themselves to sink.

Meanwhile, warming temperatures, especially in north and south poles, are melting ice that has accrued over tens of millions of years. The water from this melting drains into the sea, raising sea levels around the world.

This is not a theoretical or future threat. It’s happening, now.

“At more than a dozen tide gauges spanning from Texas to North Carolina, sea levels are at least 6 inches higher than they were in 2010 — a change similar to what occurred over the previous five decades,” the Washington Post noted recently in an investigation of rising sea levels in the southern United States.

Half the coastal cities in China are experiencing rising sea levels in relation to their shores. As many as 12 million Chinese will be living below sea level by the end of the century, Nature magazine reported.

In India, Karnataka state hosts some of the many coastal communities threatened by higher sea levels. Various government studies have concluded that a third to almost half of the state’s coastline has seen significant erosion, according to Scroll.

How fast sea levels rise is a matter of frenetic study and lots of debate. What’s certain is this: It will accelerate as long as concentrations of greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere continue to rise; Significantly more sea level rise is already baked in, unavoidable; However high the seas reach, they will not be easily reversed, at least not on anything less than a geologic time scale measured in epochs.

We’ll have to deal with higher seas.

The question is how?

The first knee-jerk urban response to this threat is good old fight or flight: build barriers to keep the water out — like New Orleans or New York City — or simply abandon vulnerable homes or communities and retreat to higher ground.

But some 3 billion people live less than five meters above sea level, a million in Australia alone, according to the World Bank. Neither fight or flight will be enough to head off what may amount to a civilizational threat over time.

That’s where Joerg and the SeaCities Lab come in.

“We have to ask ourselves, ‘What are the opportunities of sea level rise?”’ he told me as we walked across Griffith’s sunny and relaxed campus to the institute’s offices and engineering lab.

To the time-worn responses, Joerg and his team of researchers and graduate students emphasize two more strategies: “accommodation” — welcoming the water into urban areas in a controlled way — and “advance,” pushing the city and its infrastructure out into the water, either floating upon or submerged below the waves, and sometimes both.

You can see an overview of the lab’s work, along with a video here.

Some cities already have the right idea. Singapore has built a large, floating stage for public performances. Venice in Italy and most of the Netherlands have long found ways to leverage waterways for tourism and commerce.

Other cities — such as Jakarta, one of the most immediately threatened megacities in the world — are still fixated on building barriers and moving populations, despite the efforts of some of Joerg’s former students to, as they say, turn the tide.

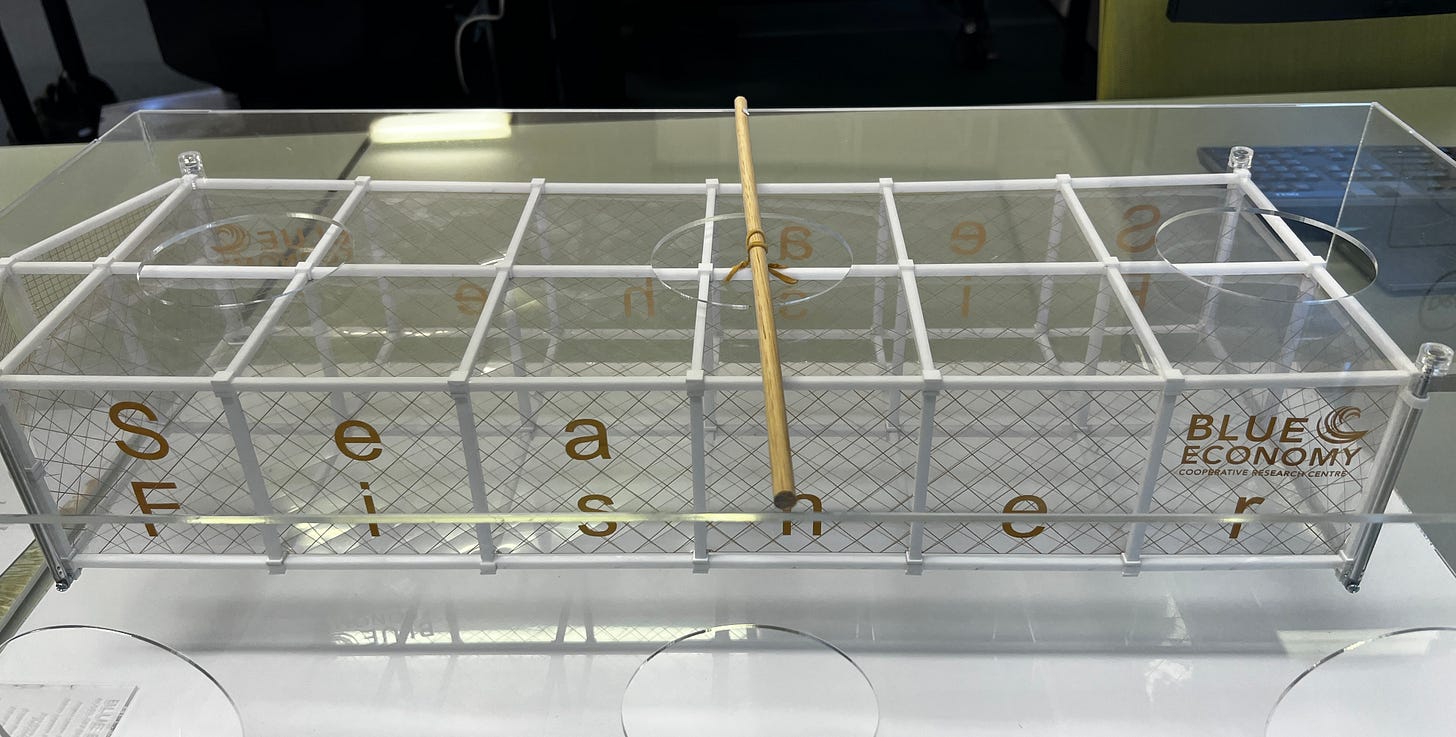

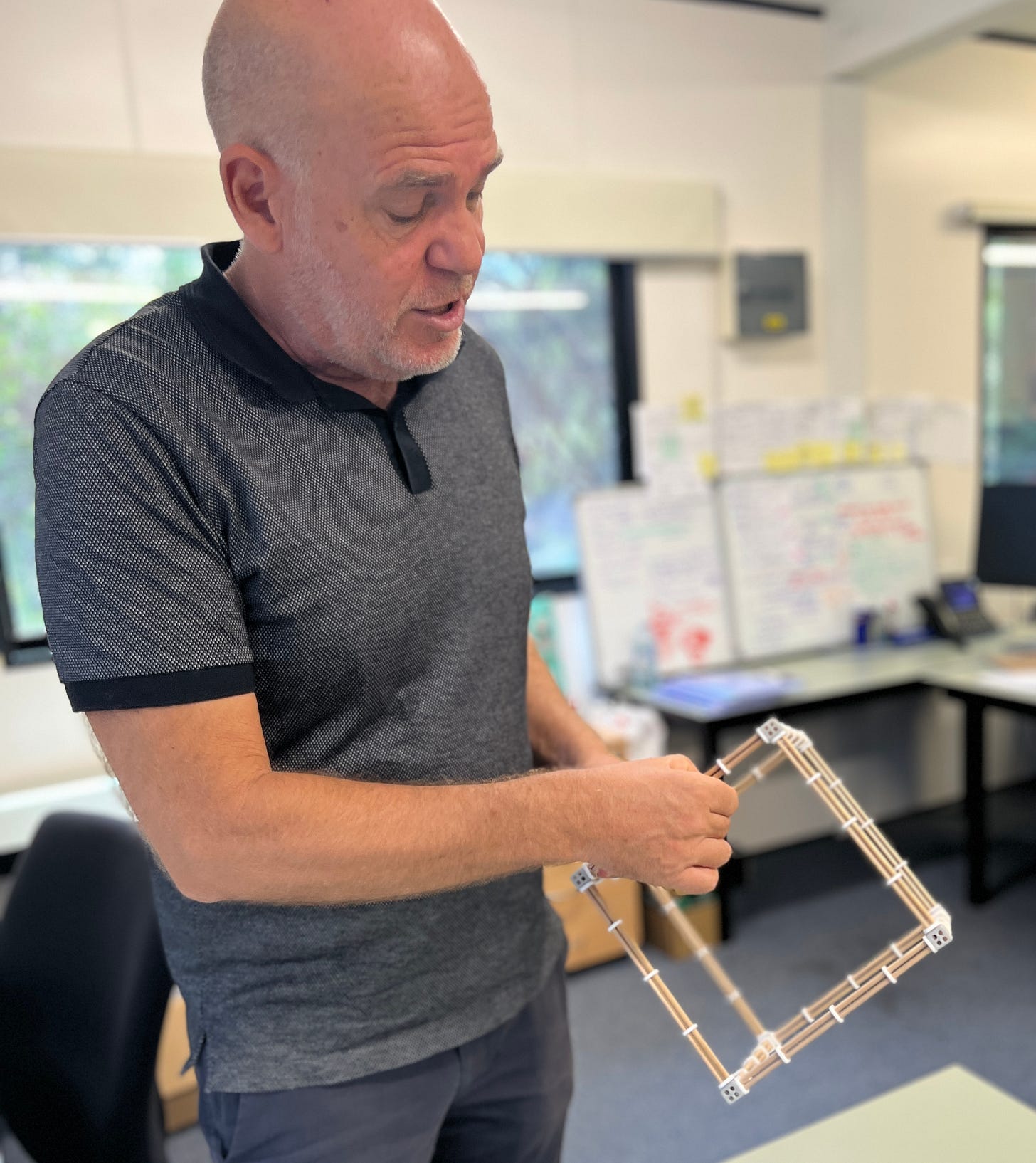

During my visit, Joerg explained several projects he and his students are working on now. One is a large, floating fish pen that could provide aquaculture options for cities, part of the lab’s effort to add to productive agricultural space and address food scarcity. The structure, to be made of recylable plastic, adapts easily to both gradual sea level rise and the more intense storms that climate change is bringing.

Bigger than a football field, the inexpensive, flexible frame would float on the surface of open water during calm weather. During a storm it would sink down under the water to better withstand the turbulence.

Some of his students are studying ways to move greenhouses and renewable energy infrastructure offshore, as well.

One student in the lab the day I was there is working with the nearby city of Brisbane to design floating beds of mangrove plants that can be used to restore wetland areas in the city. Others are working on ways to build artificial coral reefs, a response to the threat of reefs — including Australia’s Great Barrier Reef just north of Gold Coast — slowly dying off as water temperatures rise.

Still others are looking into the feasibility of large-scale, floating offshore ports that could be used by multiple countries in various regions.

Great article Bill.. such a coincidence that last nite I saw a film on nature where in northern most western Ireland that showed how the Irish Going way back… had build stone walls to fight off the incredible seas…

Twink

Great piece! If a bit terrifying.