The UAE Consensus and Fossil Fuels

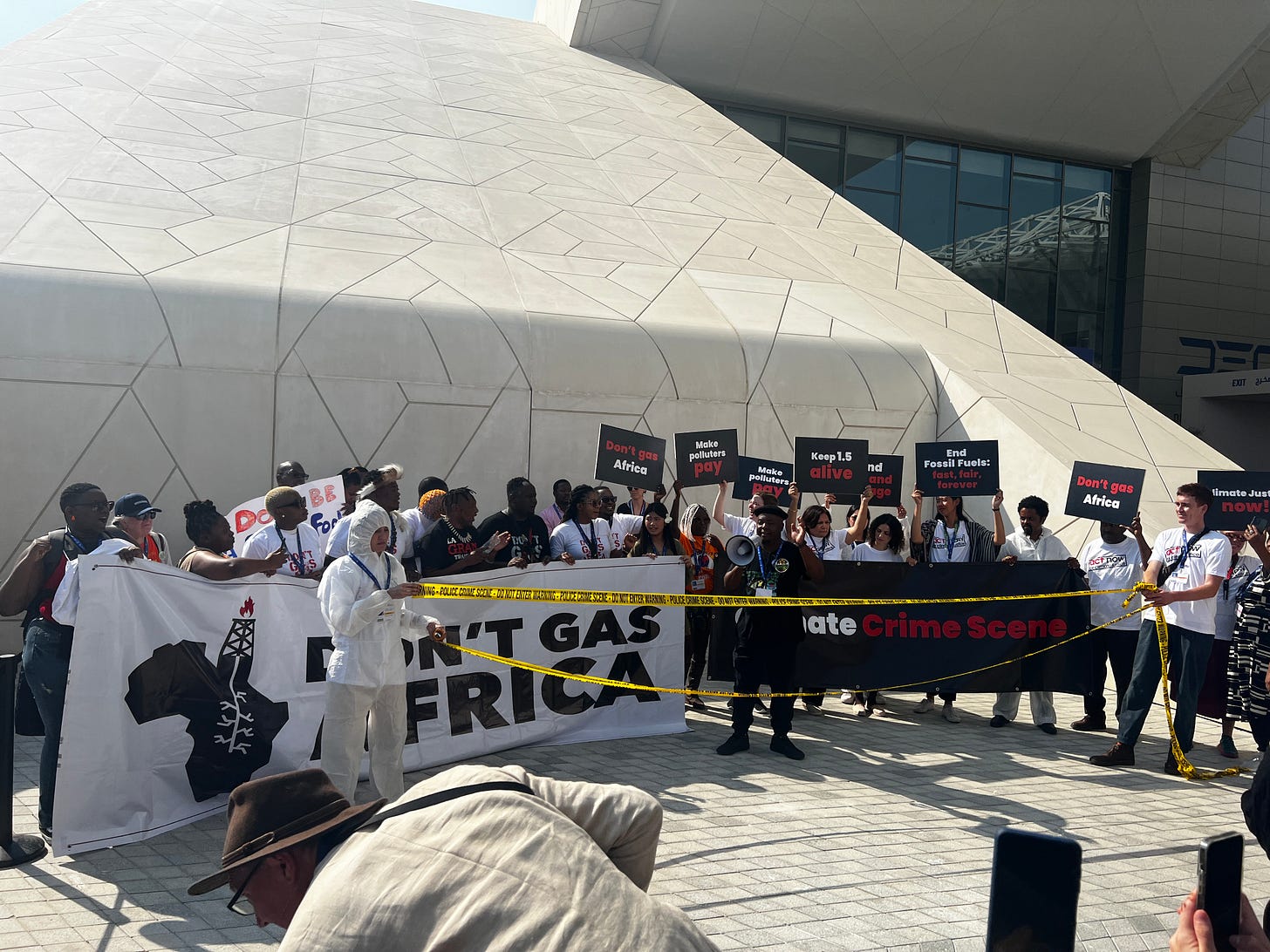

The battle to define the historic agreement at COP28 is joined as COP29 looms

A heads up that the Energy Adventure(r) has some amazing travels in the works this year, including Australia, Southeast Asia, South America and back to Japan(see here and here for our last journey there).

This is thanks not only to Cipher News, which will graciously continue to support and publish my work, but also a terrific reporting fellowship from the Alicia Patterson Foundation. I’m grateful to both for encouraging, supporting and shaping my work.

More on those trips soon. Anyone with thoughts on what to see and where to focus in these regions please reach out!

For now, I want to look ahead to the next COP climate summit, to be held in yet another petrostate, much to the dismay of climate advocates. This is not ideal, to say the least, but COP28 pointed us towards a way to counter the influence of fossil fuel advocates in the energy transition.

Read on….

Dubai’s COP28 is in the rear view mirror. COP29 looms on the horizon, scheduled for Baku, Azerbaijan in November. Fossil fuel fans, countries and companies alike, are working hard to define the so-called “UAE consensus” that emerged in Dubai, with the aim of shaping what comes out of Baku.

This is no surprise. And it’s predictable that their interpretation requires no urgent move away from any of the three big hydrocarbons — oil, gas, or even coal — despite the final communique in Dubai calling for a “transition away from fossil fuels.” They emphasize the agreement's next words, stipulating this transition be “just, orderly and equitable.” They are betting these words will become synonymous with “relying on fossil fuels,” “slowly” and “without big changes in the global order.”

But there’s an antidote to this thinking, a way to assure the “UAE consensus” comes to mean what it calls for — a transition away from fossil fuels.

The COP28 outcome was widely framed as a sort of compromise between fossil fuel interests and climate activists. But the delicate balance actually fell between two different — and, in theory at least, more reconcilable — poles.

On the one side were governments keen to undertake an urgent (though not instant) wind-down of fossil fuels as the best way to decarbonize the global energy system; on the other were countries, mostly in the developing world, determined to assure this does not happen by sacrificing the aspirations and well-being of their populations.

Think, for example, the European Union on one side; India on the other. Or small island nations existentially threatened by climate change; versus, say, South Africa or Indonesia, both of which are heavily dependent on coal to fuel their economies.

There’s a lever to break this logjam — climate finance. Or to put a finer point on it: wealthy countries investing much more in a faster energy transition, not only at home but beyond their own borders. This is what the outcome of COP29 must accomplish.

There’s no denying that watching fossil fuel advocates paint their version of the UAE consensus can be painful.

Saudi Arabia’s energy minister — Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman al Saud, a son of the Saudi king and half-brother of the country’s operational ruler, Mohammed bin Salman al Saud — raised eyebrows with a speech at a recent conference in Riyadh.

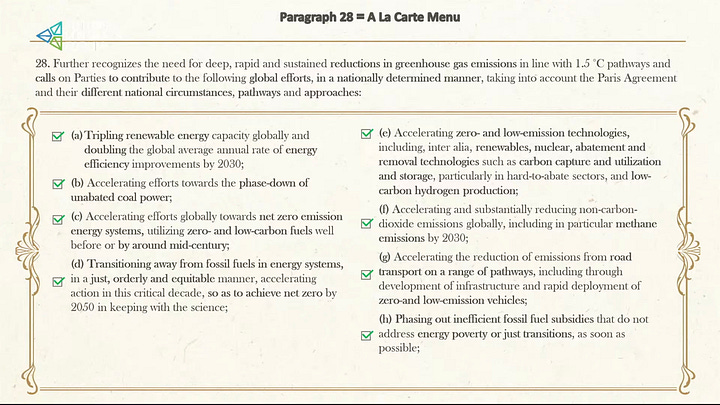

Addressing an international mining conference, the prince recast the main tenants of the Dubai agreement — tripling renewables and doubling energy efficiency and the transition away from fossil fuels — as an array of take-them-or-leave-them options to adopt, or not, in combination.

In one slide, he even displayed the unanimously agreed upon text as an elegant “a la carte” menu, as if presented by a waiter in a Paris brasserie, cursive script and all.

Of course, in Dubai, a chose-your-transition approach was specifically and roundly rejected (as this article in Climate Home News explains) — although the agreement recognized that different countries would transition at differing speeds in different ways beyond the baseline.

Other potentates at oil and gas power centers — especially Western oil and gas producers and their legions of lobbyists — have been only slightly less disingenuous. They flag provisions in the COP28 agreement allowing that certain “transition fuels” (read: natural gas) “can play a role in facilitating the energy transition while ensuring energy security.” Many of these voices come from oil and gas producers in the U.S., which is now the world’s top producer of oil and gas in history.

Both tactics boil down to the same bet by fossil fuel interests. It’s that developing countries in South and Southeast Asia, Africa and Latin America will insist on the “just, orderly and equitable” transition that was agreed upon — and the developed world, the ones with the money that can make this happen, won’t come through.

Countries like India and South Africa are not in love with fossil fuels. Nor are they dependent on them in the same way as petrostates and oil and gas companies whose economies rely on exporting these resources. The truth is, were the up-front costs for renewables comparable — on a scale just as large, to be available not someday but soon — many more developing countries would sign on in a very, very big way.

India, maybe the best example, already embraces a future of renewables and electric vehicles. Every Indian government is burdened by the bill for oil and gas imports. Indians suffer from air pollution caused by burning coal. India is already striving to make the transition from fossil fuels happen — to the extent it can. But it needs foreign investment to speed this up.

Helping developing countries, largely on commercial terms that make investors money, is key.

How will fossil fuels be phased (mostly) out?

It begins, and likely will be continuously led by, by cutting demand through substitution. That doesn’t mean there’s no reason to target supply, especially massive new sources such as liquid natural gas exports that encourage more demand. But for the most part, supply — managed collectively by organizations like OPEC and more individually by oil and gas interests — will follow reductions in demand, and keep following as needed.

Here China provides an interesting test. The country is unique in that it is both developing (low-ish per capita income) and developed (world’s second largest economy). It is a huge consumer and importer of fossil fuels (particularly oil and gas), as well as a massive producer (of coal).

China has the economic wherewithal not only to finance its own energy transition, but to decide for itself what that transition looks like and where it ends.

And increasingly — for all the confusion the country is creating by ramping up coal use even as it laps the world in building renewable energy — China appears serious about transitioning away from fossil fuels in precisely the way the so-called UAE consensus describes: phasing down fossil fuel use at first gradually (2030-2035) then dramatically (2035-2045), replacing them with the full fusilade of clean energy options, in a way that’s orderly, just and equitable across the vast expanse of this critical nation. This recent analysis by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air shows how China is pouring investment into clean energy, to the extent these industries kept its economy afloat last year.

So far, there are indications that electric vehicle sales are growing at rates fast enough to begin eroding demand for oil and wind, solar and nuclear power are growing fast enough to overtake electricity demand growth and increasingly push coal into the role of security backup and less and less frequent use during peaks.

That, essentially, is a microcosm — big as China is — for what the world as a whole needs to accomplish, starting with reductions in fossil fuel use in the U.S. and Europe but also by unleashing a flood of clean energy finance from all sources — U.S., Europe, the Middle East petrostates, South Korea, Japan and China — into the developing world to build alternatives to fossil fuels faster than demand in the developing world grows.

Should that happen — and making it happen needs to be job #1 of COP29 — it won’t matter what fossil fuel interests think or want.

They’ll go along, because they’ll have no choice.