The Pika Principle

Polar Bears get all the press, but these diminutive inhabitants of the high alpine have something to say about global warming, too.

Few critters have done more for climate research than the pika.

Never heard of a pika?

Here’s one:

Pika look like rodents, but they are actually related to hares and rabbits. They likely got started as a species in the Himalayas. They’re among very the few mammals that thrive above the tree line in high alpine ecosystems — habitats that are warming ahead of the rest of the world.

Pika, like their fellow frigid weather fans the polar bear, face the prospect of their habitats shrinking as the climate warms. They’re canaries in the coal mine, and scientists have studied how they’re responding in the U.S. and beyond.

One puzzle: despite significant warming, pika populations are doing better than expected, so far at least. What explains this resilience?

I learned about pikas from Tomoki Sakiyama, a 29-year-old graduate student at Hokkaido University, during my recent trip to Japan’s northernmost island. He studies the northern pika that lives across northern Asia, focusing on precisely this question.

In Hokkaido, pika live in the jagged, intricate spaces between and around massive piles of rock at high altitude. This rock started as volcanic lava flows that solidified, then broke into millions of pieces as water seeped into cracks and fissures, expanding when it froze and contracting when it thawed, through the winters and summers of time, leaving towering heaps of boulders behind.

Here’s a photo. The little blue speck in the lower right is Tomoki.

Concealed in the maze of this fragmented landscape, palm-sized pika are not easy to count. To solve for this, Tomoki carries a loudspeaker up the mountain on his back. He blasts a recording of a pika cry across the landscape.

Vocal animals, pika cry back.

Tomoki listens carefully and counts the responses. That’s how he determines how many pika there are in a given area. He’s done this for the better part of each summer for years now. Tomoki also studies the gene pools of the various pika populations, for reasons that will be clear momentarily. He gets DNA samples by collecting pika feces — the pikas themselves, again, being very hard to catch to get their DNA.

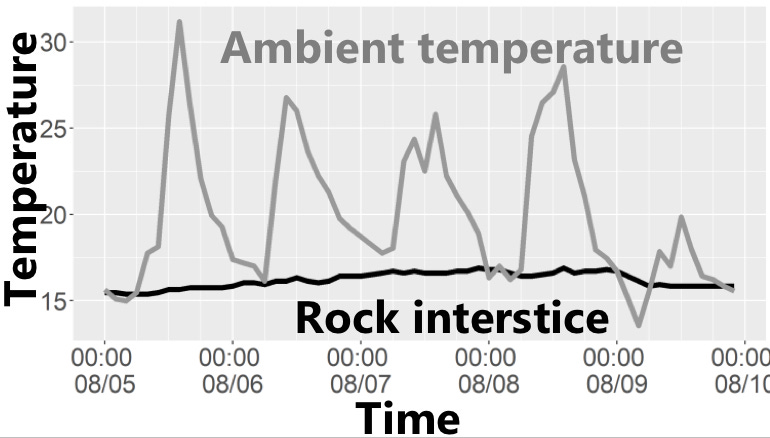

Meanwhile, Tomoki also measures the temperature of the ambient air and the air inside the rock spaces. These are the thermometers he uses:

Air temperature, of course, vascillates sharply between the bitter cold of Hokkaido’s snowy winters and the relative warmth of summer. Temperatures within the rock spaces, on the other hand, are much steadier. Beneath the snow and between the rocks where the pika live, it remains warmer than outside during the winter chill and cooler than outside during the summer heat.

Pika couldn’t survive directly exposed to outside temperatures that fall as low as -4 degrees Fahrenheit during Hokkaido’s high alpine winter. Nor can they live long in ambient temperatures over 85 degrees in the summer. But they don’t have to. Here’s what one summer of ambient temperatures versus temperatures down under the rocks looks like:

Pika thrive in their own little climate, what biologists call a “micro-climate.” What matters is less the atmospheric temperature than the temperature where they live — at least to some as yet unknown threshold.

This matters more broadly to a warming world beyond pika.

One reason pika populations may be resilient is the temperature band where they live isn’t shrinking as fast as the “macro-climate” around them. Their habitat is fragmenting as temperatures rise, not uniformly retreating up the mountain, and their populations may be fragmenting as wel, not disappearing uniformly.

If proved out, this could have broader implications for conservation efforts, according to Tomoki. As temperatures rise in the coming years — inevitable given the greenhouse gases already belched into the atmosphere — we’ll struggle to preserve the complex of life around us, biodiversity we as a species also depend on.

We may find ourselves in a situation where global warming first advances then retreats as we reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Conserving lingering ecosystem pockets may be just as important — or more important — to recovering biodiversity.

“If we can predict, or know, where these small, very functional pockets or patches will be, that has a very high conservation value with climate change. That particular spot can remain as a very nice refuge for the species to persist in the future,” says Tomoki.

I love pika! Have seen lots of them in their rocky habitat in hikes in Zanskar as a teenager, they are so sweet and this research is fascinating+ encouraging

"as we reduce greenhouse gas emissions" is really optimistic. I don't believe we'll see that anytime soon considering the activities of your red state GOP governments.