We come again to the question of fossil fuels and their role in the energy transition. They’re hard to get away from, since they’re mostly the problem. But oil and gas companies keep trying.

That’s for obvious reasons — as transparent and, frankly, delusional, as these may be. It’s hard to come up with a winning business strategy that ends in the elimination of your main product — although hardly unprecedented in the annals of business history.

As long as the fossil fuel industry keeps trying to avoid this reality, others will feel compelled to underscore it.

For decades now, oil, gas and coal executives have been on a rocky public relations journey when it comes to climate change.

From roughly the early 1960s until, well, not all that long ago, outright denial of climate change was the message. This was despite plenty of internal research at the oil majors, especially Exxon Mobil, that pointed to the burning of fossil fuels as the cause. Oil and gas companies have shifted to acknowledging climate change, but arguing little can really be done to reduce fossil fuel use for decades to come without denying the world — especially the developing world — the energy it needs.

Most recently many have turned to arguing that the problem is not fossil fuels, per se, but the emissions that stem from burning them. While literally true, this is disingenuous. The entire world — including every country in the Organization of Oil Producing Countries (yes, OPEC) — willingly agreed at the most recent United Nations’ climate conference in Dubai that fossil fuels are the problem.

The stark conclusion there was that the world needs to transition “away” from them. Yes, there were stipulations and caveats. But the bottom line was clear: oil, gas and coal are the heart of the problem. They need to go.

Can’t happen overnight. Might even need to keep using a bit for some purposes forever. That’s what net zero means. But pretty much gone is where they need to be by 2050, which means we must start weaning ourselves off them now.

So I was somewhat — though not totally — surprised earlier this month when my experience at New York’s Climate Week involved so much about the staying power of fossil fuels.

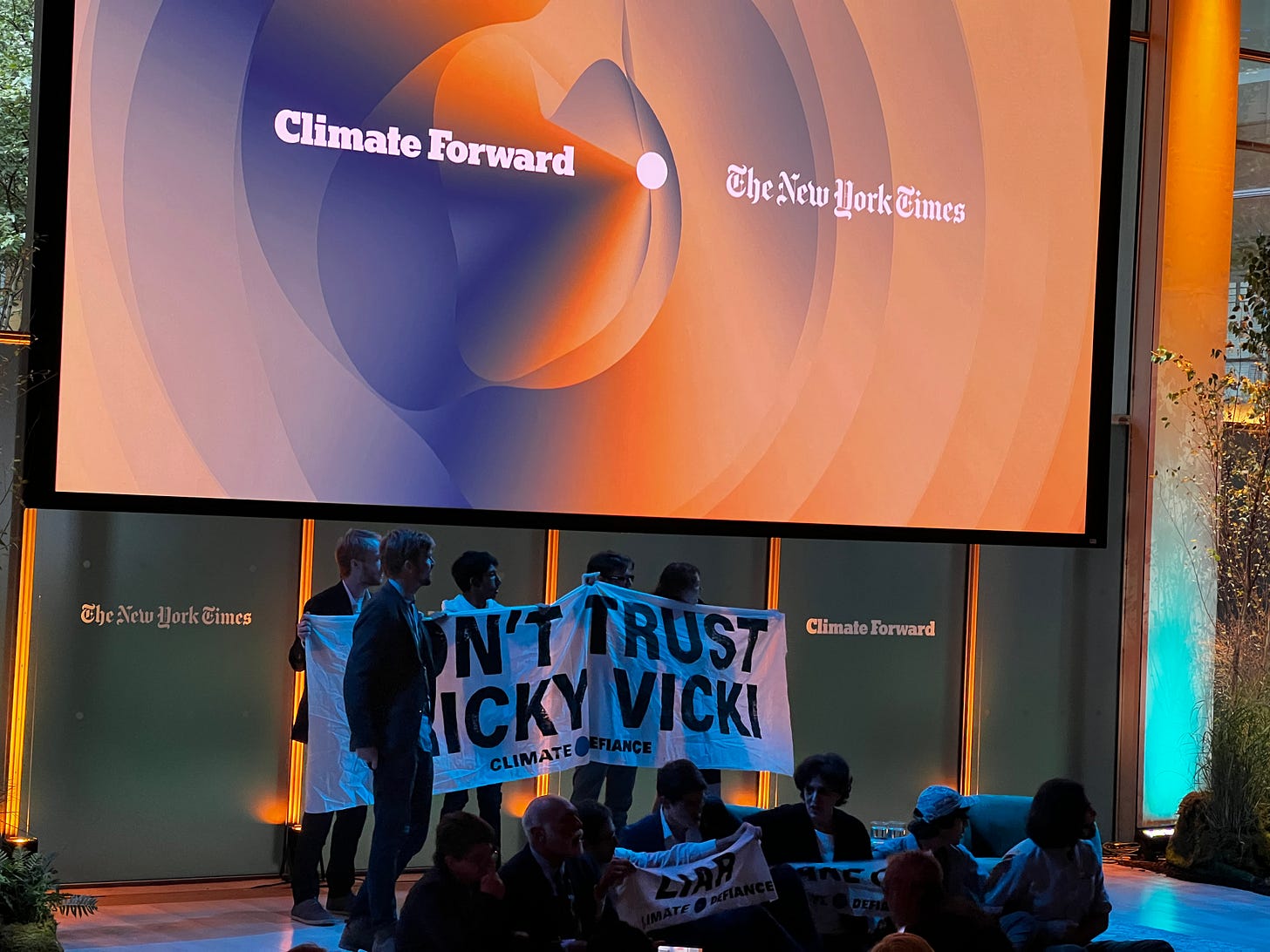

On the first day, I participated in a panel discussion at the New York Climate Exchange as part of a “Climate Taboo” series. Panelists were asked to debate, or at least speak to, the question: Should fossil fuel companies be paid to keep their products in the ground? The next day, I was sitting drowsily at an afternoon New York Times event when several dozen anti-fossil fuel protestors leapt up and took over the stage as a prominent oil executive — Vicki Hollub, chief executive of Occidental Petroleum — was entering for a so-called “fireside chat,” the sort of earnest dialogue Climate Week specializes in.

David Gelles, the New York Times columnist presiding over the conference, and the conversation, abruptly turned Hollub around and ushered her off the stage. Demonstrators unfurled banners and shouted slogans lambasting Hollub, the fossil fuel industry and the New York Times for inviting this conversation with an oil gas executive.

The demonstrators were noisy and stubborn, refusing to leave until police arrived and arrested them. Hollub was defiant. She insisted, after the auditorium had been cleared of protestors, attendees and even credentialed media other than the Times, that the interview with Gelles go on as part of the conference’s online broadcast.

For protestors and Hollub the dust-up was hardly unique. The incident was another calculated move in a high-stakes wrestling match between the fossil fuel industry and its foes.

Hollub’s disrupted appearance was the defining moment of this year’s Climate Week for me — the only time when the real urgency and difficulty of the challenge before us burst to the fore, despite countless other mentions of the “climate crisis.”

I thank both the protestors and Hollub for that — as well as the New York Times and Gelles for bringing them together within earshot of each other, albeit unintentionally.

That’s because I think this this sort of confrontation is still necessary, even desirable. Both sides are underscoring real issues that must be wrangled with for the energy transition accelerate — as it must.

Take the question the panel I moderated took up: Pay fossil fuel companies NOT to sell their products?

Seems outrageous, the answer an obvious, no? Both Alice Evatt and Stephen Gardiner raised a raft of concerns about doing this — from the extortionist nature of paying to avoid harm, which can seem a lot like extortion, to the vast sums of money that would be needed to make a difference.

Yet just months ago I was in Southeast Asia reporting on a deal orchestrated, backed and funded by climate activists and philanthropists that would do precisely this. The agreement, one of several like it under consideration, aims to close a coal plant on the island of Luzon, Philippines more than a decade early by paying the owners the full value of their power contract.

As a practical matter, it’s difficult to see the coal plant being shut down early without such an arrangement — as desirable and as necessary as that would be, and as much as its owners should by all rights be stuck with a stranded asset they bet wrong upon.

So to some extent, some owners and operators of fossil fuel plants will have to paid off. This is going to be part of the solution, the greater goal being fewer emissions and a faster transition to clean energy rather than solely to punish fossil fuel investors.

In the case of the deal in the Philippines, the owner is at least assuring the plant will close early. They could simply sell the facility to another company that might run it on coal to the end of its useful life.

That brings us to Hollub and Oxy (as Occidental is widely known). In the audience-less, online interview, Gelles pressed hard. Hollub is the vanishingly rare oil and gas chief executive who talks about climate with urgency and has devised a corporate plan that acknowledges a change in their business is needed.

For Oxy under Hollub, that means capturing carbon, handling it, using it and storing it — the emerging industry of “carbon management.”

To be sure, a whole lot of carbon management will be needed in the coming decades, maybe more, while the world transitions “away” from fossil fuels, as was agreed by all in Dubai. Here’s the trouble with Hollub, though: she says she and Oxy don’t believe in moving away from fossil fuels. Most of the carbon the company captures right now goes right back into declining oil wells, helping to push out more oil and prolong their life, a process known as “enhanced” recovery.

Asked pointedly when she thinks the world will stop using them, she told Gelles, “when we’ve used the last drop of oil and gas.”

Now, I’m convinced Hollub doesn’t actually believe this.

Like all oil and gas industry executives today, she lived through the “peak oil” panic of the 1990s. Conventional wisdom all but concluded the world’s reserves were nearly tapped out, only to witness a gusher of newfound oil that wild-catter ingenuity collectively dubbed “fracking” brought forth over the ensuing three decades.

As a practical matter, there’s really no end to the amount of oil and gas that can be found, only a price that would make it too expensive to extract. “The stone age didn’t end because the world ran out of stones,” a Saudi oil minister once famously quipped.

Hollub is signaling to Oxy’s investors that the company intends to eek every penny of profit from its oil and gas business for as long as it can, even while it tries to build a carbon management business on top of this.

She knows investors would bail fast and the company’s stock would crash if she said anything other than this. Selling oil, gas, and even coal, remains profitable.

Falling share prices have been the fate of European oil and gas companies whose leaders signaled anything less than a full-throated, never-ending strategy of extracting and selling oil and gas.

Warren Buffett, the legendary investor and owner of about one-third of Occidental, regularly sings Hollub’s praises, once said, “She’s doing exactly what I would do if I were her.”

I have no idea what he was specifically referring to, and no way to find out. But I’d bet he’s referring exactly to Hollub’s two-faceted strategy of pursuing fossil fuel profits while opening the door on new businesses that depend, to one degree or another, on their eventually being phased out.

Even if Hollub and other fossil fuel executives understand fossil fuel demand is all but certain to peak and eventually begin falling, there’s plenty of reason a shrinking market could prove lucrative if the supply of oil, gas and coal consistently shrinks more slowly than demand — providing pricing leverage to those with supply.

Riding those resources down profitably will be hard for investor-controlled companies to pull off in competition with much larger national oil companies such as Saudi Aramco. It finances a kingdom of 40 million people and can’t easily wind itself up and disappear after paying out all its investors.

Hollub’s strategy is to build out a carbon management business with the profits from oil and gas sales. It’s not unlike how major publishers, like the New York Times, have deployed profits from a lucrative but ultimately doomed print newspaper business to fund a transition to a fully digital product.

Of course, the New York Times’ legacy print business wasn’t the main driver of the climate crisis. Oxy’s legacy oil and gas industry is precisely that, along with its fossil fuel brethren.

And that, ultimately, is where the protests come in. The disruption they cause, by design, can be disquieting. I found it jarring to discover the true identity of one person who sat at my table during a lunch discussion about the challenges of the climate crisis and energy transition.

He introduced himself to the group as a musician, simply there to learn more about the climate crisis and what could be done about it. An hour or so later there he was, thrusting his fist and shouting anti-fossil fuel slogans as part of the demonstration.

He clearly wasn’t there just to learn. Two can play the disingenuity game.

My point, though, is that it must be played, and the sooner the better to get on with the transition.