Fighting Fires on Kangaroo Island

One of Australia’s natural gems will recover — if a changing climate allows it.

I recently spent three weeks reporting on climate change and energy transition in Australia, the world’s smallest continent but a potential renewable energy powerhouse. Although the country currently gets more than 90% of its energy from fossil fuel and is the world’s fourth-largest exporter of coal, Australia has some of the best wind and solar resources in the world and plenty of space to develop them.

The state of South Australia has already pushed renewable energy to 70% of power generation today and plans to get to 100% by 2030. To learn more about that, read the story I wrote for Cipher here.

But Australia, with its unique and quirky collection of plants and animals, is also getting hit hard by climate change. Its magnificent coral reefs — including the Great Barrier Reef, longest in the world — are suffering “bleaching” events from rising ocean temperatures. It’s dying, other words. A shift in ocean currents bringing warmer water to the coast of Tasmania has all but wiped out massive underwater kelp forests, once home to a rich array of ocean life.

The country also suffered a staggering wave of bush fires four years ago during a record stretch of hot and dry weather. The massive blazes consumed huge swathes of countryside, sending smoke across Asia and ultimately around the world.

I visited Kangaroo Island, a large, beloved island off the coast of southern Australia, to have a look at how its ecosystem is recovering four years on.

Recovering — present tense, as in ongoing — is the right way to describe it.

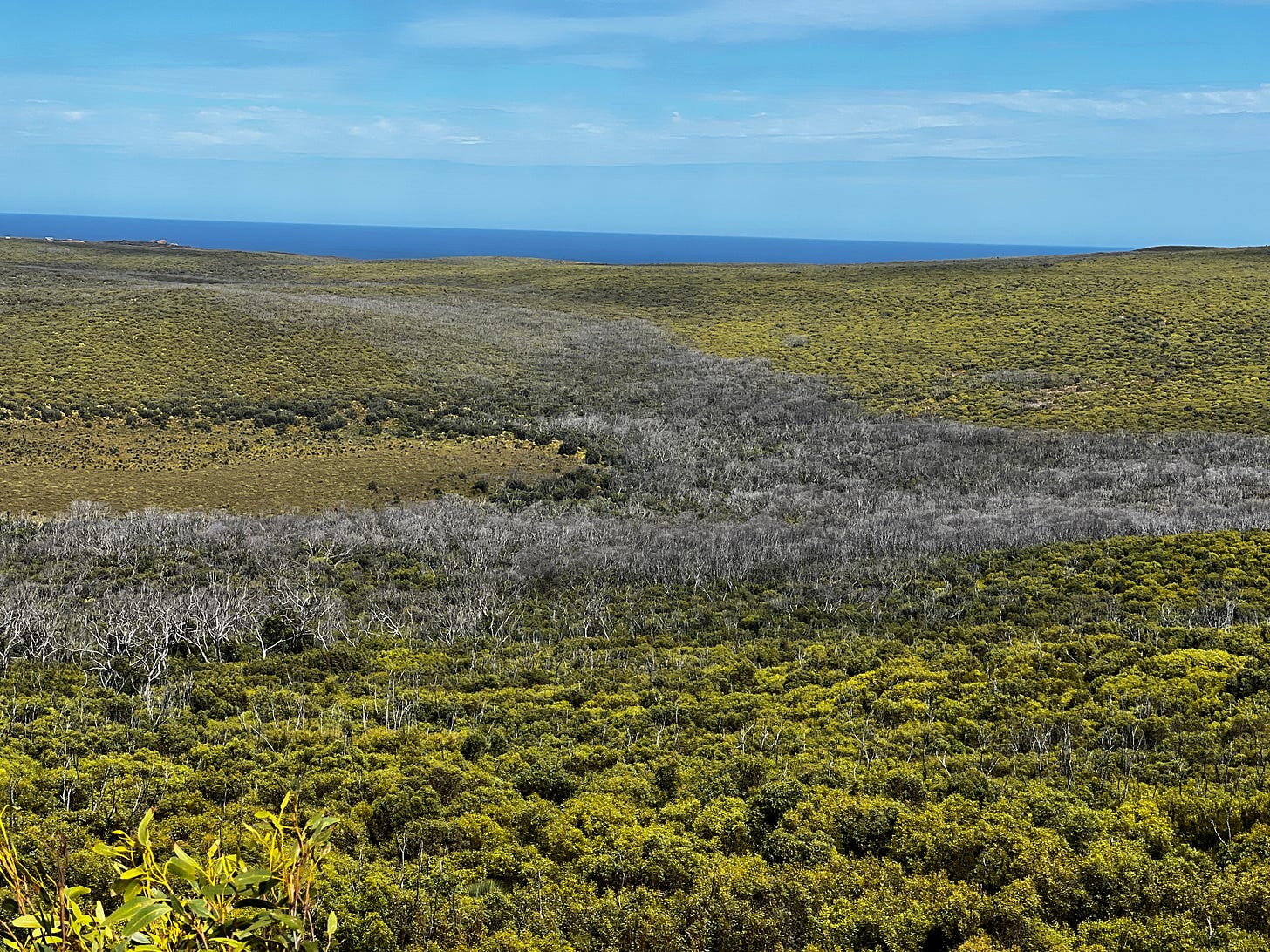

While much as grown back, as we’ve seen nature will do when given the chance, it’s very much still a work in progress.

Heiri Klein, ecologist, forest ranger and sometimes firefighter, has not forgotten the night of fear and chaos four years ago as an out-of-control inferno swept across Kangaroo Island.

Bushfires — started by lighting but fueled by a long stretch of hot, dry summer weather at the end of 2019 — had been blazing across the island, and much of Australia, for the better part of a month. While seasonal fires are regular occurrences here, these blazes were something altogether different — gigantic conflagrations consuming vast swaths of brush and pushing out smoke and carbon emissions on a scale so large that scientists are only now fully assessing their global impact.

On the night of Jan. 9, 2020, Klein and thousands of residents on the island at the time were focussed on the danger closest to them. Fires had already engulfed much of the western side of the 1,700 square mile island, most of which is protected national parkland. Prevailing winds had changed direction and picked up speed, pushing flames into the eastern half of the island, which is populated with farms and the island’s main towns of Kingscote, American River, Parndana and Penneshaw.

The situation suddenly shifted from evacuation orders into what locals call “too late to leave,” meaning now best to stay put and take shelter however possible. Klein’s fire brigade, already exhausted after weeks of battling fires, was told to give up and return to headquarters, itself in the process of moving for a second time to get out of the way of the rapidly spreading flames.

“They thought the entire island might be wiped out in one night,” he told me during a tour of the island recently.

This was the height, on Kangaroo Island, of the largest wildfires in memory across Australia — a trauma the islanders, the country, and even the planet is still recovering from three years on.

The 2019-2020 bushfires tore through 59 million acres, an area the size of the United Kingdom. At least 33 people and perhaps 1.5 billion wild animals perished. More than 3,000 homes were destroyed in the various conflagrations.

Research since then has concluded the fires have cost the tourism industry $2.8 billion Australian dollars ($1.8 billion U.S.). Forestry was also hard hit. Smoke from the fires spread to the country’s main cities, across Southeast Asia and eventually the globe, exacerbating air pollution harmful to millions of people.

“These results are an illustration of what can be expected in the future not only of Australia, but in other nations that are vulnerable to climate-change driven disasters,” the lead author of the study told the news outlet Mongabay earlier this year.

Smoke from the fires likely skewed weather patterns across the planet, lowering temperatures to below what they would have been otherwise for several years by reflecting back sunlight. That cooling effect running its course last year may be part of what’s behind global temperatures in the last year shooting to all-time highs on land and, especially, in the oceans. And of course, that heating was caused in part by the carbon emissions from the fires themselves, equivalent to more than a year’s worth of Australia burning fossil fuels. Like all carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere, it will remains there for at least a century.

Klein, who has lived and worked on Kangaroo Island with his wife and their two sons for 19 years, was kind enough to show me around Kangaroo Island, which sits a 45 minute ferry ride off the coast of the state of South Australia. Fire damage is still apparent — right alongside the remarkable recovery the island’s ecosystem is making. It is, as Klein explained, an ecosystem used to adapting to fire. Indeed, the island’s unique ecosystem depends on periodic blazes to sustain itself.

But not fires like this one. This one consumed in the span of a few weeks half the island, torching more than 95% of the wild areas protected as national parkland in the island’s west. Maintaining the ecosystem requires substantial numbers of plants and animals to survive fires in order to easily repopulate the scorched areas. In this case, only a few tiny swaths were spared, making the road back long and tenuous.

But much life has returned. Rangers and scientists are still cataloging the extent of the long-term damage and exactly what to do to fix it — or help it fix itself.

Klein drove me through areas where nothing remained immediately after the blaze except a landscape of “black and white,” charcoal and ash. Today, many of these areas have replenished themselves as green flora and fauna of all sorts have returned — animals including kangaroo and wallaby, duck billed platypus, echidnas and koalas, swamp rats and the endangered Glossy Black Cockatoo. It’s also provided an opportunity to control one major invasive creature — feral cats, a problem throughout Australia — and push another — wild boars — close to eradication.

He stopped his jeep often to walk into the brush and point out this regeneration happening. For the keenly adapted Banksia plant, this starts in the heat of the fire, the moment of maximum destruction.

He grabbed a Banksia cone to explain how its fireproof resin protects the seeds from the heat. After the fire passes, the resin softens, and the seeds are released into the nutrient rich, ashen soil. They grow quickly with little competition from other plants, providing shelter and food for animal survivors moving in from areas where they escaped the fires.

“Literally within a few weeks, we started to see these green shoots everywhere,” Klein said.

At another stop, Klein showed me Yacca plants, some of which have lived hundreds of years enduring dozens of fires. While their leaves burn profusely, they protect their living core with layer upon layer of growth packed together over time into a tight cover. They send out rapidly growing flowers soon after a blaze.

With the usual bushfire patterns over thousands of years — smaller, scattered burns that turn patches to ashes while leaving others unburnt — that’s all part of the delicate balance that makes a sustainable ecosystem. Without those burns taller plants come to dominate, choking off the lower level from sunlight.

But if Australia’s climate continues to veer toward hotter, drier conditions on average in the coming decades, that, too, will permanently alter the ecosystem of Kangaroo Island along with the rest of Australia. It’s the same lesson I learned in an earlier trip to India: ecosystems bounce back from even the worst shocks, but not from the repeated blows a changing climate is dealing in ever-quickening cycles.

“These are fire-prone systems. They’ve evolved with fire. Without fire, a lot of our ecosystems collapse,” Klein told me.

At the same time, recovery becomes impossible if there are too many fires, too frequently burning too much of the ecosystem.

“It’s clear with analysis that these horrendous fires were partially driven by climate change,” he said. “If you get 40 degree days, which we had in December of 2019 and January of 2020, and you get 40 kilometer per hour winds, then you have catastrophic conditions.

“And of course we will get, statistically and empirically, more of these crazy conditions. The fire intervals will probably get shorter. Fire intensity will probably go up on average. And so the question becomes, can these ecosystems withstand fires of a frequency they didn’t evolve with?”

Bill- I had no idea about the bleaching issue along the Great Barrier Reef, so this is an enlightening find. I’m so thankful you’re highlighting this for awareness.