Biodiversity in the Big City

A successful effort to reclaim a tiny patch of India’s polluted capital is a hopeful reminder the planet can recover. If it’s not pushed too far.

One third of Pakistan under water from a deluge of rain and glacial melt. California broiling under all-time record heat, in September. A “doomsday” ice sheet melting in Antarctica.

The challenges of climate change and the transformation of our lives needed to address it can seem overwhelming. Is it even possible to fix a planet this far gone?

A visit to a unique nature park located on one of the earth’s most despoiled rivers, within one of the world’s most densely populated and polluted cities, was a reminder of just how resilient the earth ecosystems can be. Addressed properly, damage can be reversed.

But only if the planet isn’t pushed too far, very much our current trajectory.

Few cities are as polluted as Delhi, and even fewer with the size of its population, approaching 30 million people. The Yamuna River, which runs through the megalopolis, consistently ranks among the most despoiled waterways in the world. The pollution in the 900 mile waterway comes mainly from Delhi, which contributes up to about 80% of the pollutants despite taking in about 2% of the river’s length.

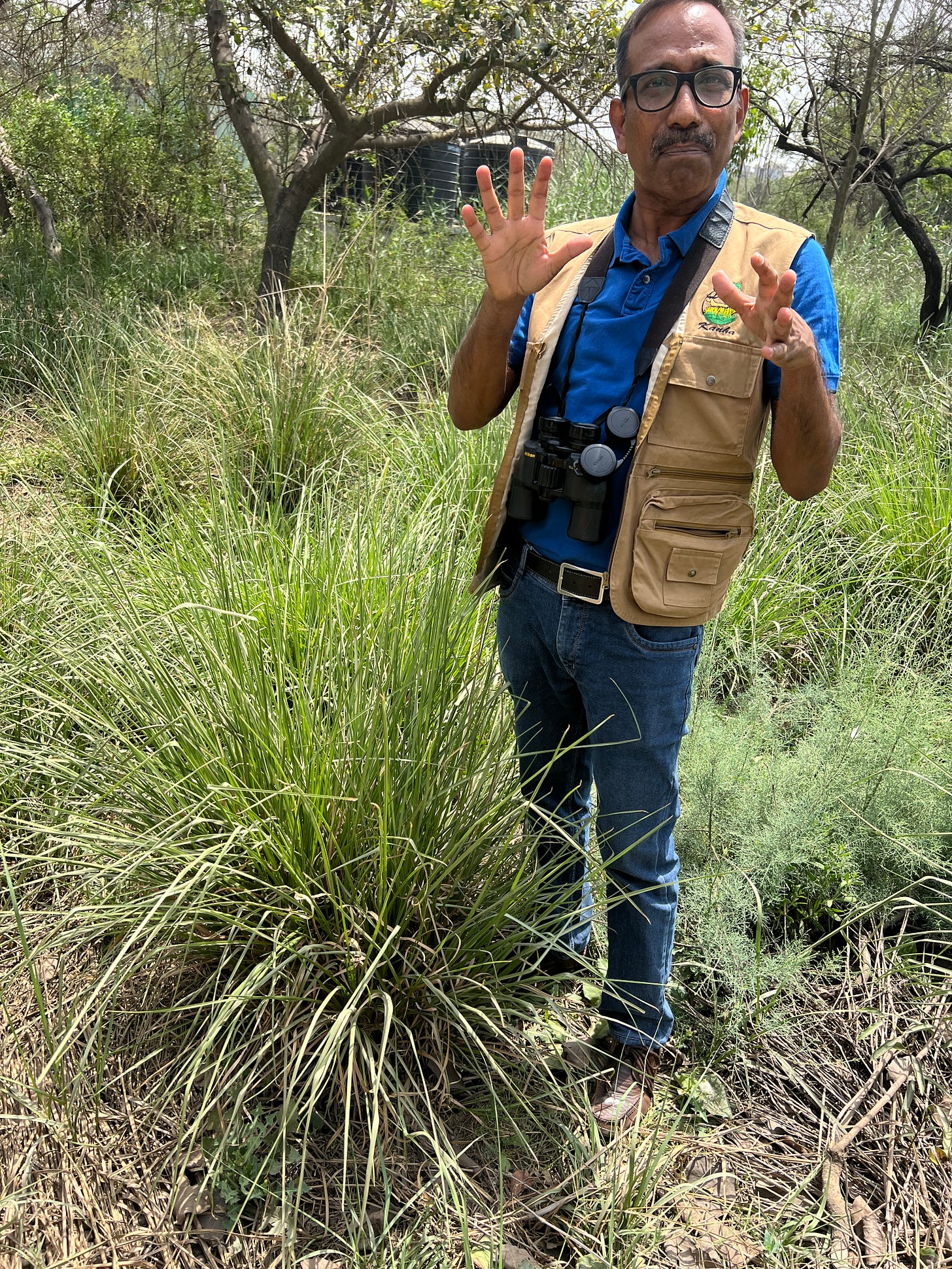

Yet Dr. Faiyaz Khudsar, a professor of biology at The University of Delhi, gave us a tour of an extraordinary stretch of the river.

Like Dr. Krishna Ray, who we met earlier in the journey working to restore mangrove habitats in India’s Sundarbans, Khudsar studied under Prof. C.R. Babu. Babu trained many of India’s prominent environmental scientists, including Ray’s spouse, another botonist whose research has focused on restoring Himalayan ecosystems. Babu pioneered many of the principles of what he calls “reconstructing” severely degraded natural habitats. As we saw with Ray’s work in the Sundarbans, it takes many years and often starts with grasses that gradually change the microbial and chemical composition of the soil so that other native species can re-establish themselves.

“This is the only way to preserve the natural heritage in urban centers, where most of nature has been wiped away,” Babu told me before we set off on our visit of the park.

Khudsar’s enthusiasm for this patch of nature he’s helped restore is infectious, and comes through in this similar tour available on YouTube.

As the native flora and fauna gradually returned over the two decades, Khudsar says larger ecosystem rallied.

“Species we lost 100 years ago started coming back and breeding,” he said, including Hog Deer, wild pigs, snakes and Horned Owls.

One day in 2016, a leopard — common in the area more than a century ago — showed up. This thrilled Khudsar: proof the habitat had reached maturity. But when the leopard killed two goats outside the park, wildlife authorities trapped it and brought it to a reserve far from urban populations.

“It was ready to stay, but the forest department wasn’t happy with so many people around,” he said.