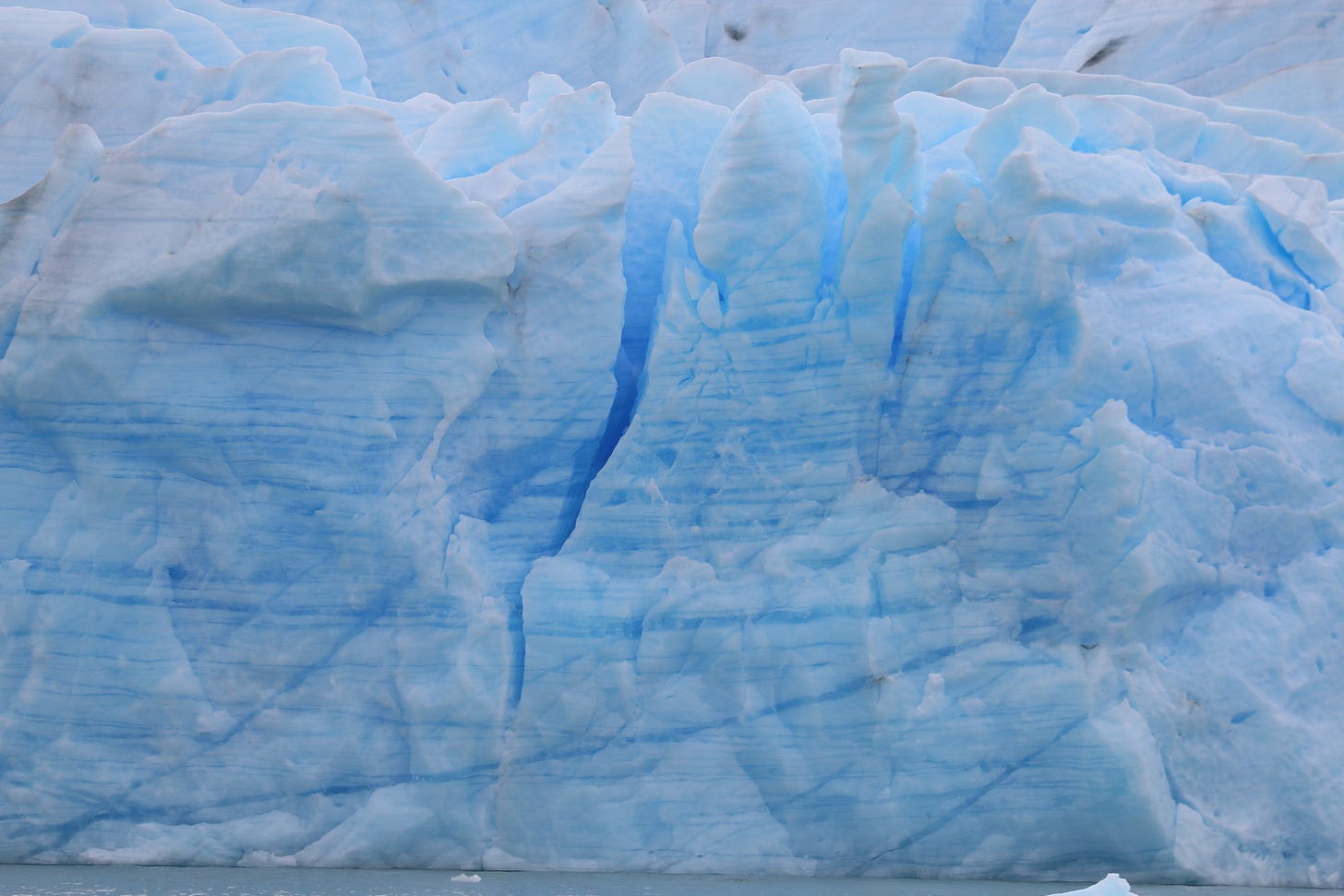

Few places are more removed from the bustling world than the Southern Patagonia Ice Field. This pile of super-compressed snow — the second-largest glacier in the world outside the poles, ice so pure it’s a luminescent blue — straddles the border of Argentina and Chile high in the Patagonian Andes.

I recently gazed across the enormous tongue of the glacier that extends down a long valley in Chile until abruptly falling off into a mountain lake in the Torres del Paine National Park in Chile.

This is the Grey Glacier.

It did indeed feel far removed from the bustling world. Here the busy streets of New York, where I live, are hard to imagine, much less the grinding horrors of Gaza, the Ukraine war front or the steady pop-pop-pop of ebulent yet vaguely alarming releases of artificial intelligence models from Silicon Valley.

Or the bureaucratic din of Washington D.C., where the Biden administration was racing to finish what work it could before the arrival of team Trump — like the rush of water away from shore as a tsunami gathers force.

The Trump tsunami has hit by now, of course, roiling D.C. as I write this. Its fury makes pondering the plodding threat of climate change seem as far removed from the real world as I felt peering over that exceedingly remote, seemingly solid block of ice, larger than the land-area of Connecticut, way up in the Andes Mountains.

Yet…this sort of remove does provide some useful perspective.

My last post summed up 2024 as a year of reckoning, coming to terms with both the reality of climate change and the daunting challenge of addressing it. Irresistible force meets immovable object — or so it feels.

With this post I’m starting to think about some new ways forward.

The first reason to do this, Grey Glacier makes clear: fallout from climate change isn’t going away because the world is focused on other priorities.

As solid and immovable as this Connecticut-sized ice block looks, it’s anything but. The Southern Patagonia Ice Field was once part of a larger expanse of ice that covered all of Chilean Patagonia during what’s known as the Last Glacial Period, roughly corresponding to the late Pleistocene Era ending about 11,700 years ago.

Since then, as the planet slowly warmed, the ice here has been melting. And Grey Glacier has been receding, its meltwater flowing from beneath, the tongue calving off chunks as it’s retreated up the valley. So that’s nothing new.

What’s new is the speed with which this is happening of late, reflecting the acceleration of the heating of the planet caused by the rapid accumulation of greenhouse gasses from human industrial activity starting in the 1870s.

The planet is not just heating up, it’s heating up ever faster as greenhouse gasses continue to accumulate in the atmosphere. That’s melting the Southern Patagonia Ice Field ever faster. Grey Glacier, which is just one edge, is retreating at about 100 meters a year now, way above the average over the last 11 millenniums.

Over time, as the entirety of what was once the conjoined Patagonian Ice Field dissapears altogether, a small but not insignificant contribution to global sea level rise is taking place. This is only one of the many, many serious impacts of climate change not only not going away — others being wild fires, hurricanes, droughts, floods and more. They’re getting worse, faster.

Whatever other priorities rearing their heads, whatever backlash against climate concern is afoot, it’s no longer viable, anywhere, to deny or downplay the climate challenge out of existence. Or to wholly dismiss as “alarmist” the obvious need to start now on what’s admittedly going to be a lengthy, complicated process of winding down fossil fuels to a fraction of their current use.

This isn’t just a hope on my part. It’s evident in the rest of the world’s conspicuous refusal to fully jump on Trump’s let’s-not-be-bothered climate bandwagon.

Meanwhile, something else is clear from this remove: the paroxysm of activity in Washington, at least when it comes to the energy transition, is as much as sound as fury. Not meaningless, to be sure. The setbacks here are real and disheartening, especially for a governmental role to push things along. But willing fossil fuels to the center of the future global energy system won’t make it happen, and wishing renewable energy out of existence won’t work.

Why? The very things Washington’s new fossil fuel zealots constantly talk about: cost and energy security.

Solar, wind, battery and other clean energy technologies are expected to fall by a record amount for the second year in a row, according to new research from BloombergNEF. This makes them especially competitive against fossil fuel alternatives in areas of fast-expanding demand, such as Southeast Asia and Africa. But even in the U.S., where gas is far less expensive than anywhere else in the world, falling solar and battery costs are fast-approaching parity with gas generation on a lifetime cost basis. BNEF expects the cost of clean technologies to fall between 22% and 49% further over the next decade. That’s stunning for technologies whose cost has been plummeting for a decade now.

China, and increasingly India, see renewable energy — particularly wind and solar in combination with batteries to store energy and power transportation — as the key pillar of energy security going forward. These two markets are so huge, they’re already driving production volumes, in their effort to limit fossil fuel imports, to levels so high that much of the rest of the world will piggyback on them to address their own energy insecurities. We’re already seeing this in Pakistan, where homeowners and businesses sucked in an astonishing number of inexpensive solar panels from China last year. Southeast Asia, Latin America and even Europe are suddenly turning to Chinese electric vehicles. China is already figuring out how to expand, and then win, these overseas markets by helping build out grids and charging networks. The U.S., meanwhile, is fixated on selling them liquified natural gas they see as a potentially useful stopgap but not really solving their energy security needs.

And the third leg of the energy trilemma, the one the team Trump rarely mentions but the rest of the world remains acutely concerned over: Sustainability. This is less environmental sustainability or a direct nod to climate than a realization that to the extent clean, renewable energy can be made to work — i.e. meet the cost and security criteria above — it’s vastly more sustainable than wading into a volatile global market on a daily basis to acquire energy sources that must be extracted from one place on earth and floated to another on ships across unpredictable, increasingly vulnerable sea lanes. This doesn’t make the switch easy — and does extend the use of coal for those countries that have it — but provides a strong ongoing incentive to make it happen.

None of this, sadly, means the energy transition will accelerate sufficiently to beat the escalating impacts of climate change at the pass. And it’s no consolation that neither was the previous climate-concerned consensus getting us there anywhere near fast enough either, really. Progress since the much-ballyhooed Paris Accord has come as much as a result of the three factors cited above as from the willful effort of nations working together to address the problem.

That isn’t to say the Paris Accord wasn’t effective, or worth the effort. Only that, as I’ve been saying since COP27 in Egypt, we’ve moved into a post-Paris world. The agreement accomplished many important things, but it’s increasingly ill-equipped to facilitate what’s needed going forward in this world as it is today.

What, if anything, can be done? How, if there is a way, to best address the gaping void in globally coordinated action, the faux-action from yesterday’s climate-concerned world no less than today’s suddenly climate-dismissive one?

That’s what I’m thinking about now and will post about soon.

You know what I think, Bill!

Thanks for your writing and photos!