Patagonia is many things, but first and foremost a very long way from anything else.

That’s the overwhelming impression for a first time visitor like me, whether driving through Argentina’s northern Patagonia desert…

…hiking near the southern ice sheet in the Andes Mountains

…or on an island full of penguins in the Strait of Magellan in Chile.

This remoteness has long presented a challenge for utilizing the region’s resources. It’s an age-old problem for the energy industry: Resources, tantalizing as they are, often exist far from where they’re needed, desperate though that need may be.

The main energy resource in these parts was once whales, when their oil was a prized lubricant and the premium fuel for lighting. Whalers, with their giant ships and crews of harpooners, found a way to meet that demand.

They scoured the oceans…

….secured the resource…

…transported it to far-away cities where demand was soaring.

And packaged it up for sale:

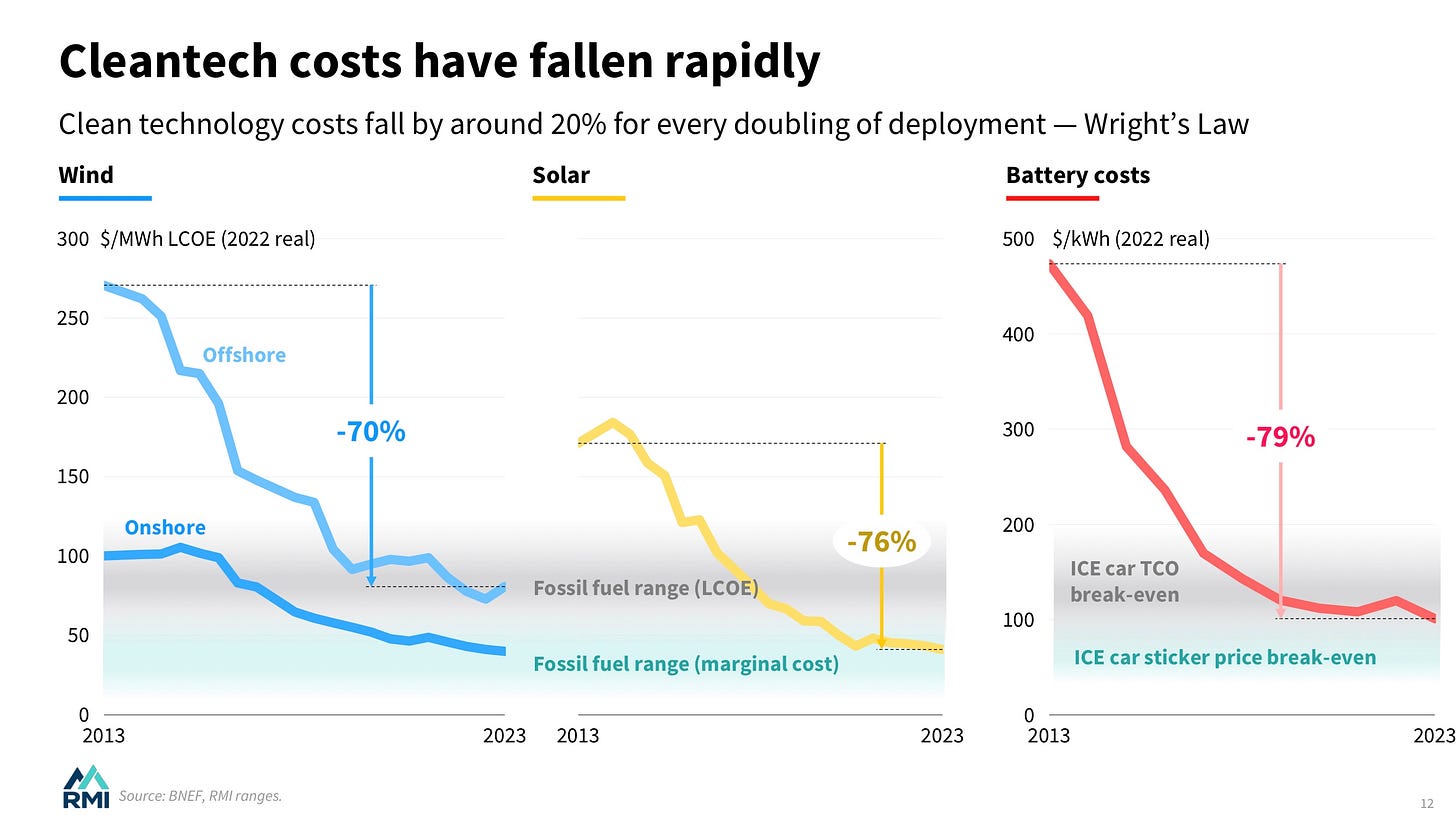

When fossil oil came into vogue much the same thing happened. A century of pipeline and tanker making ensued. These were woven into a network of supply and demand so comprehensive it’s sometimes hard to imagine any other way to get energy.

Oil and gas have been a heavier lift for Patagonia, but Argentina’s Vaca Muerta geologic basin has been a bigger and bigger exporter of oil over the last few years.

Natural gas has followed the same path. First pipelines were constructed over shortish distances — within the U.S., for example; from Russia to Europe, from Qatar to the United Arab Emirates — to carry the gas. Then came the ships, huge vessels capable of transporting natural gas in a frigid, dense liquid state from port to port. With this, natural gas (in the form of liquified natural gas, or LNG) went global.

A lot like oil.

There’s even more natural gas in the Vaca Muerta than oil — though getting it to demand centers is still proving a challenge.

All this shipping around of oil and gas costs the world hundreds of billions of dollars each year and creates megatons of greenhouse gas emissions, beyond what’s expended burning the fuel.

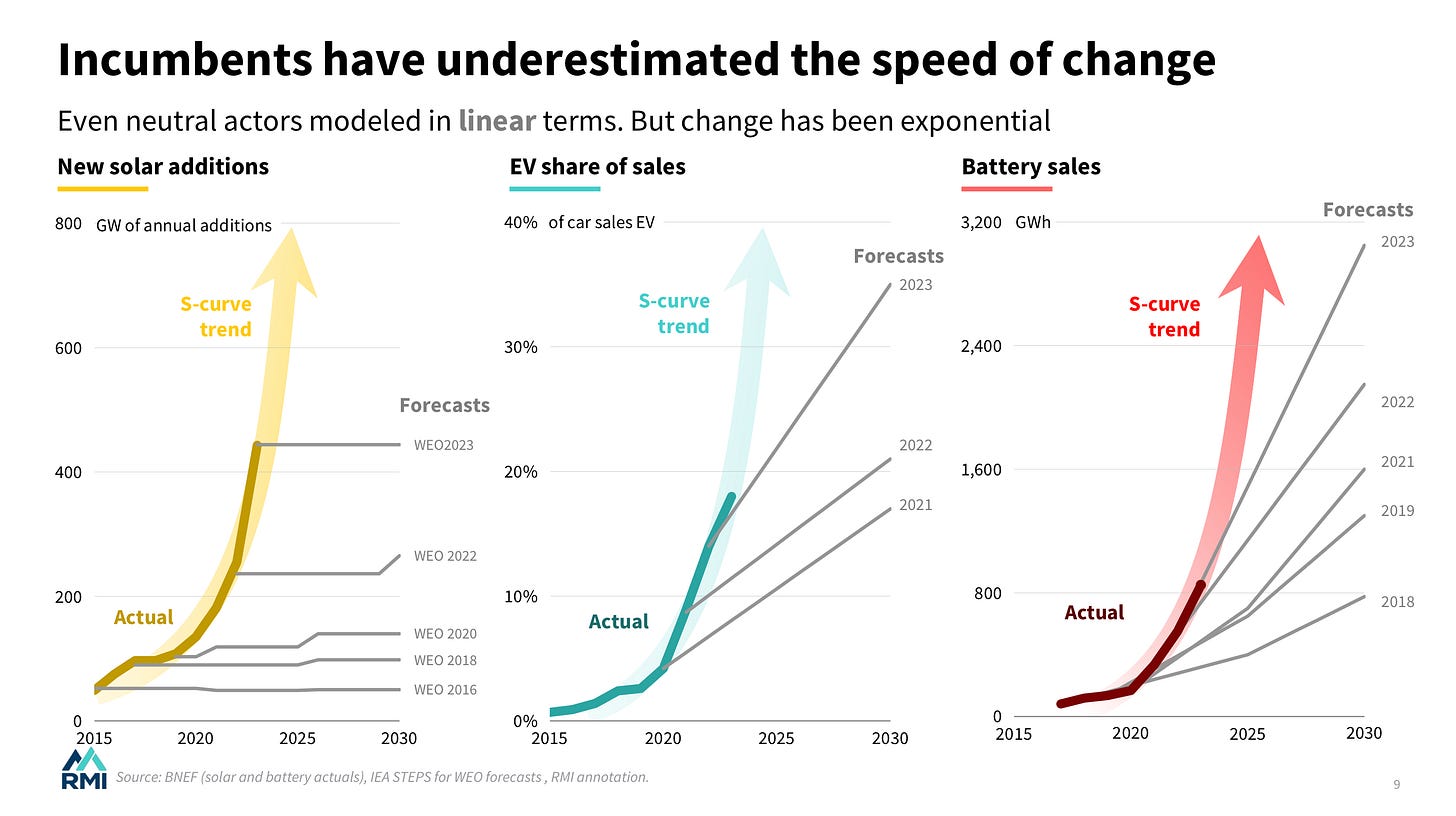

Here renewable energy has a big advantage. Almost every country has at least some sun and wind (as well as heat from geothermal energy from far underground, another very promising emerging clean energy source). Some of the best renewable resources are plentiful in places where people most it — Africa, South Asia and Southeast Asia in particular, where they’re still burning wood and dung for fuel.

Energy that doesn’t have to be shipped across oceans, through vulnerable maritime routes, gives renewables a real competitive advantage in an increasingly volatile world, according to one of the world’s leading commodities analysts, Jeff Currie of the Carlyle Group.

“If trade is under threat, then so are fossil fuels,” Currie writes in a recent report that’s made waves in the oil and gas world. “Non-fossil fuels are not traded and grow in demand when energy security is paramount.”

But wind and solar do have a version of the supply-demand disconnect: some places have better resources than others; those places aren’t necessarily near where the energy is needed.

This isn’t always a huge problem: China has a stupendous amount of wind and solar energy in its remote interior. Building high-voltage power lines to coastal cities has proved workable where the authoritarian government can make things happen.

The U.S. has a similar situation in midwestern plains states like Iowa, Nebraska and Oklahoma. Their vast wind energy potential is a long ways from power-hungry big cities like Chicago, Los Angeles or the eastern seaboard between Boston and New York. Realizing this potential has proved impossible so far, given political wrangling over renewables and not-in-my-backyard opposition to super high voltage transmission lines like those in China.

Patagonia represents another dimension of this challenge for renewables: bridging even longer distances across international borders.

In Patagonia spin some of the most productive wind turbines on the planet, producing electricity under the region’s unrelenting winds. That translates into some of the cheapest electricity anywhere…If it could only be put to use.

Silvina, my Argentine journalist guide, and I visited two large wind farms, one owned by Pampa Energía near the city of Bahia Blanca and the other owned by Genneia near Puerto Madryn.

Both of these wind parks — and others in these areas — are churning out exceedingly low-cost electricity that’s poured into the local grid to be consumed by customers in the area. That grid is connected as far north as Buenos Aires, Argentina’s largest city.

But the winds in this area could be producing far, far more electricity if only there were more buyers who could access and use it — which right now there aren’t. Finding more demand would might mean running an undersea transmission cable to Brazil, the nearest far more populous country.

That would be an expensive undertaking, not one that’s under consideration in Argentina. But efforts like this are underway elsewhere. There’s already an international transmission cable bringing power from Laos to Singapore.

And there are initiatives to run undersea high-voltage transmission lines 2,700 miles from Australia to Singapore, 2,500 miles from Morocco to England and 2,400 miles across the Atlantic from Canada to Europe.

A project I visited in Chile it demonstrating another potential way of bridging the source-to-end-use problem: turn wind power into physical fuels that store energy chemically — just like oil and gas — to be transported by ship, also like oil and LNG, to where there’s energy demand.

The Haru Oni facility, owned and operated by the Chilean company HIF, was built to demonstrate that the strong winds off the Strait of Magellan can be harnessed to make hydrogen, which in turn can be used to make clean fuels.

The hydrogen can be combined with other chemicals to make these “e-fuels,” the “e” signifying electricity. At Haru Oni, the plan is to combine hydrogen and carbon dioxide pulled from the air with a giant machine — also powered by the wind, and under construction when we visited — to produce methanol (a shipping fuel) or gasoline.

Other projects on the drawing board for the region aim to use hydrogen to make ammonia, another transportable compound that can be combusted later or used to make agricultural fertilizer or refined petroleum products.

These are all considered “drop-in” fuels that can be used to power airplanes, ships and other things that are difficult to do directly with electricity. Because the fuels are made with carbon dioxide pulled from the atmosphere, they’re considered carbon neutral, in a word, sustainable.

Still, these sustainable fuels are far more expensive than the fossil fuels they replace.

A final option for bridging the resource-end use gap is bringing the end use to the resource. That’s along the lines of what South Australia officials I met early last year in the city of Adelaide are puzzling over.

The state of South Australia has so much wind and solar power that renewables already make up three-quarters of the electricity generation. They’re shooting for 100% by the year after next.

The plan from there includes trying to process the state’s plentiful iron ore using hydrogen produced by renewable energy. Currently the ore is shipped overseas, mainly to China, where it’s processed using coal, which emits lots of greenhouse gases.

The clean hydrogen-processed ore would then be shipped to China and elsewhere to be made into low-carbon steel.

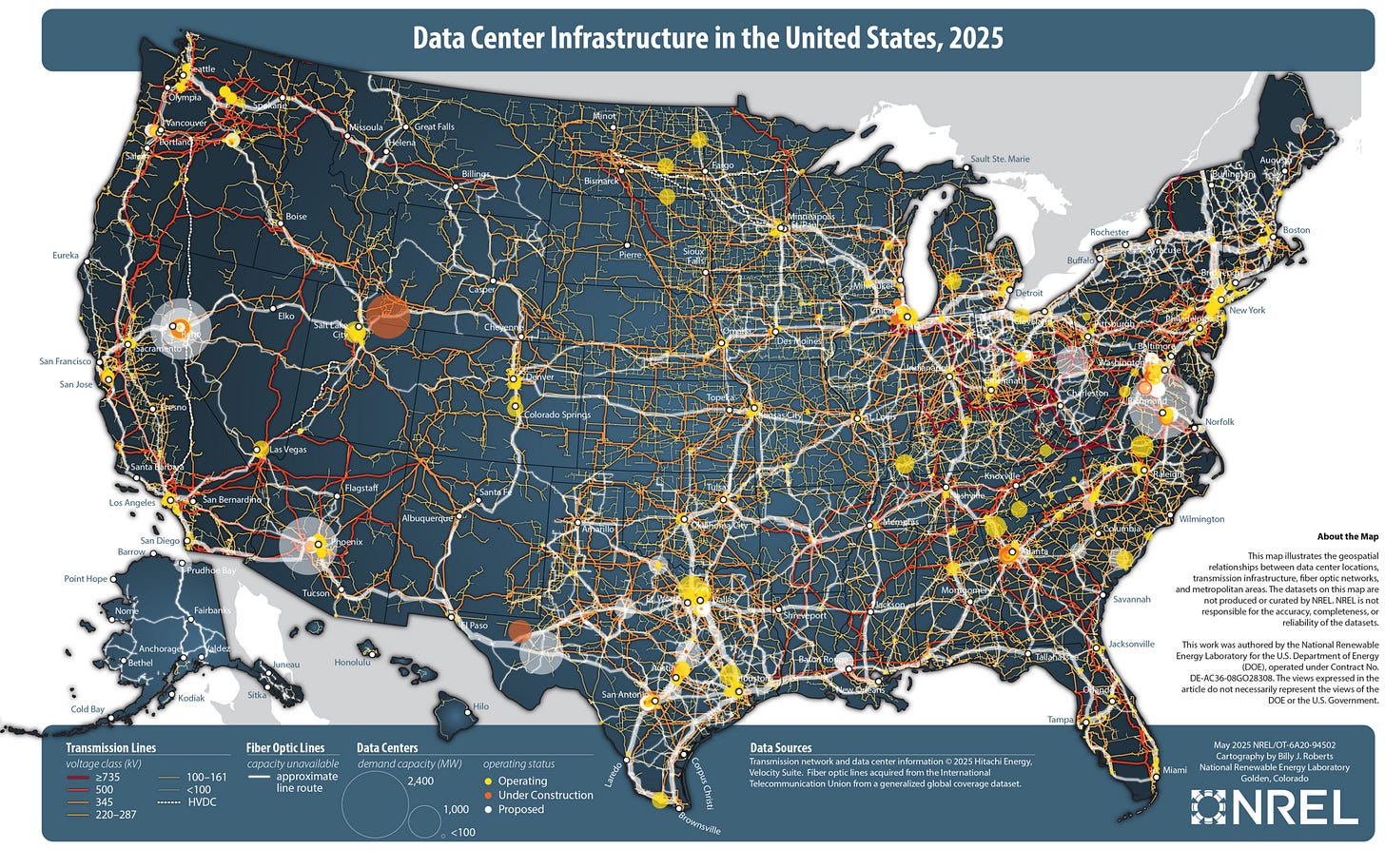

Another growing source of demand that could potentially come to these distant energy source: data centers that house the computer chips that power artificial intelligence. That way the data would be making the long trip through the undersea cable, rather than the energy.