It’s the debate of the century. And not just the century so far, but looking forward to the world’s 2050 net-zero target date and 2100 beyond:

How fast can clean energy replace dirty fossil fuels, if they can at all?

The arguing has reached a crescendo with the arrival of the second Trump administration, with its caustic anti-climate, pro-hydrocarbons agenda.

But Trump II is far from the only reason. The energy transition hasn’t progressed as the climate concerned had hoped — even under the pro-climate, hydrocarbon hating Biden administration. Trump will actually have to work hard to outdo his predecessor in the energy dominance department. Biden saw the U.S. ascend to become the largest producer of fossil fuels in the world, ever.

As I mentioned in my last post, I’ve been at CERAWeek, a huge energy conference run by Global S&P in Houston, the business capital of America’s oil and gas patch. The event billed itself as the energy industry’s “most influential annual conference.” This year’s motto: “Energy strategies for a complex world.”

On the surface, the vibe was all celebration: hydrocarbons are back!

The best attended speech came from Trump’s energy secretary, Chris Wright, who kicked off the conference by lambasting renewable energy and touting fossil fuels, to occasional cheers. But the event with the largest unexpected turnout — not Wright-sized, but clearly more than the organizers planned on — came later in the foyer of the convention hall.

Hundreds of energy executives, bankers and consultants gathered around energy guru Daniel Yergin, who started CERAWeek after authoring a epic history of the oil industry, to hear him and two co-authors discuss their most recent volley in the hydrocarbons-versus-renewables debate, an article in Foreign Affairs magazine. Headline: The Troubled Energy Transition.

I took the surprisingly large turnout as a sign. Beneath the conference’s exuberant exterior lay a lot of unease among the hydrocarbon crowd. As you can read here in my story about the conference for Cipher News, the industry is not oblivious to the tectonic shifts shaking the energy landscape today.

This trio’s article seemed to offer some solace.

Hydrocarbons aren’t likely to be replaced anytime soon, argued Yergin and his two co-authors, the CEO of investment bank Lazard Peter Orszag and S&P strategist Atul Arya. The energy transition, for the foreseeable future, will really be an “energy addition,” with new sources of energy being piled upon old ones, as has always been the case since humans figured out how to harness fire to burn wood and dung.

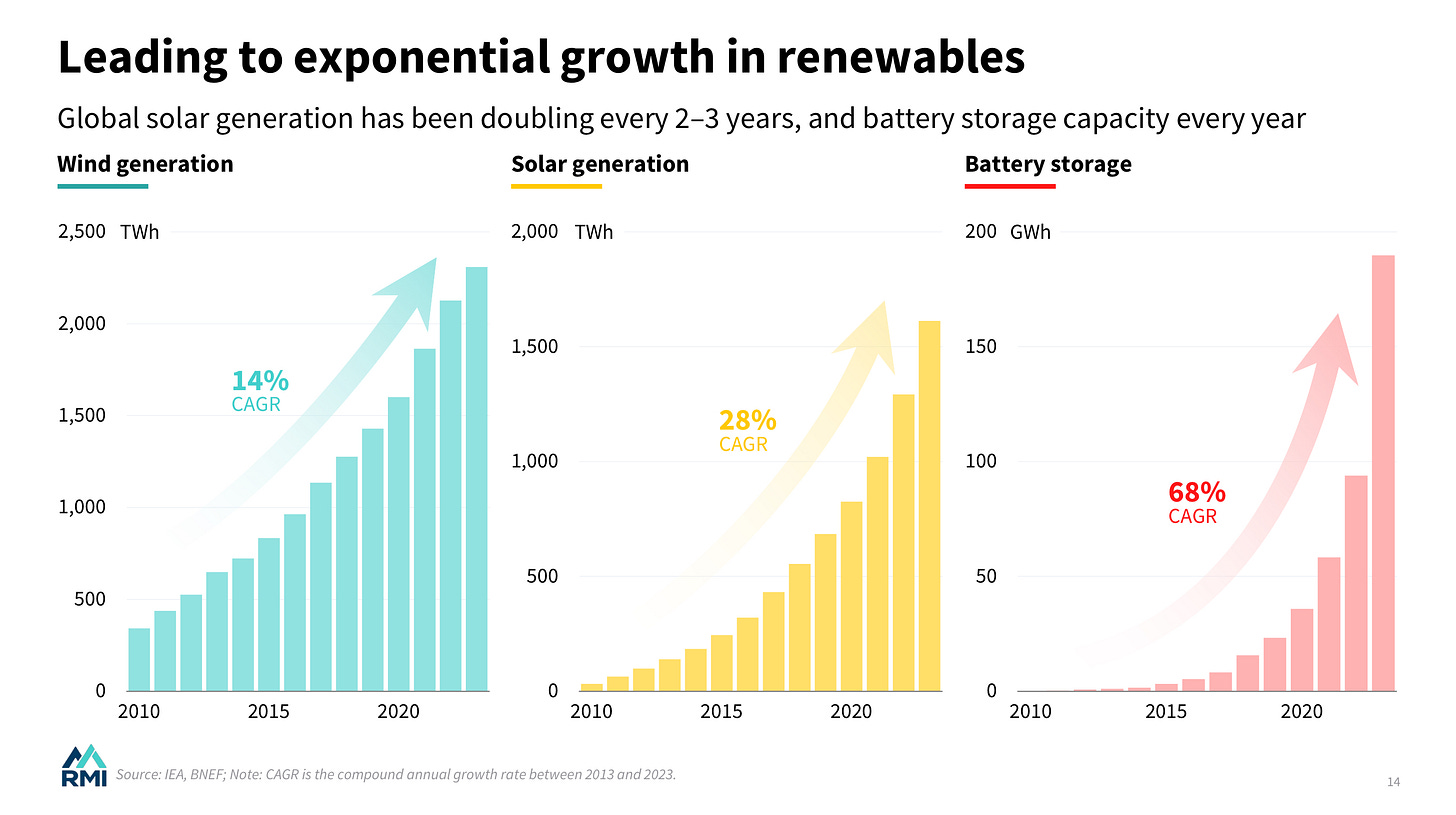

So far, of course, that’s exactly what’s happened. Fast-growing wind and solar energy have met most of the new demand for energy globally. But because overall energy use has grown even faster, coal consumption has actually gone up in the aggregate. As populations in Africa have grown, the total amount of wood and dung being combusted in homes hasn’t fallen. Global oil demand is still inching higher. Natural gas consumption has soared.

Pushing fossil fuels out of the system, even with record additions of clean energy each year, has proven too cumbersome and expensive — and will continue to be that way for decades to come, the trio argued.

The energy transition will have to wait, if it arrives at all.

Orszag, a senior advisor in the Obama administration, quickly noted for the crowd a rather important caveat that went unmentioned in the article:

“I want to say, it’s also costly not to transition,” he cautioned, alluding to the rising cost of dealing with extra floods and fires, more intense hurricanes, rising sea levels and other fallout from climate change.

Transitioning “is still necessary to do.”

The main point they eventually came around to making was the energy transition wouldn’t be all fun, easily pulled off, or wildly and for all profitable. It will be hard and expensive, at least up front. Pragmatism will be needed, especially in how quickly fossil fuels can be sped out of the energy system.

Ok. Fair enough. But does that mean it won’t happen, and perhaps much faster than the fossil fuel industry hopes and many “pragmatic” types find plausible and bearable?

There is another view.

It wasn’t voiced on any of the many panels I attended, or highlighted in keynote speeches. But as a card-carrying member of an industry — the news business — that has undergone an initially underappreciated, eventually massive transition in just a few decades from one economic model, print newspapers, to a wholly different one, digital delivery, I think it’s a view worth heeding.

The news business may not be the energy industry, but on some level disruption is disruption. The energy industry has entered an era of massive disruption. That much was clear from nearly every panel I attended and each speaker who took the podium.

Even Energy Sec. Wright, blustery denunciations of Biden aside, is emblematic. An oil drilling services company head, he’s also a big investor in new forms of geothermal and nuclear energy. He’s got a background in solar power. However myopically his speech catered to his boss’s predilections, however much he believes oil and gas have a future, this is a guy who knows where the energy industry is heading.

And where the energy industry is headed is towards electricity. Nearly everyone I heard or talked to at CERAWeek believed power would increasingly be the source of economic betterment and energy security the world over, whether it’s generated with coal, natural gas or renewables.

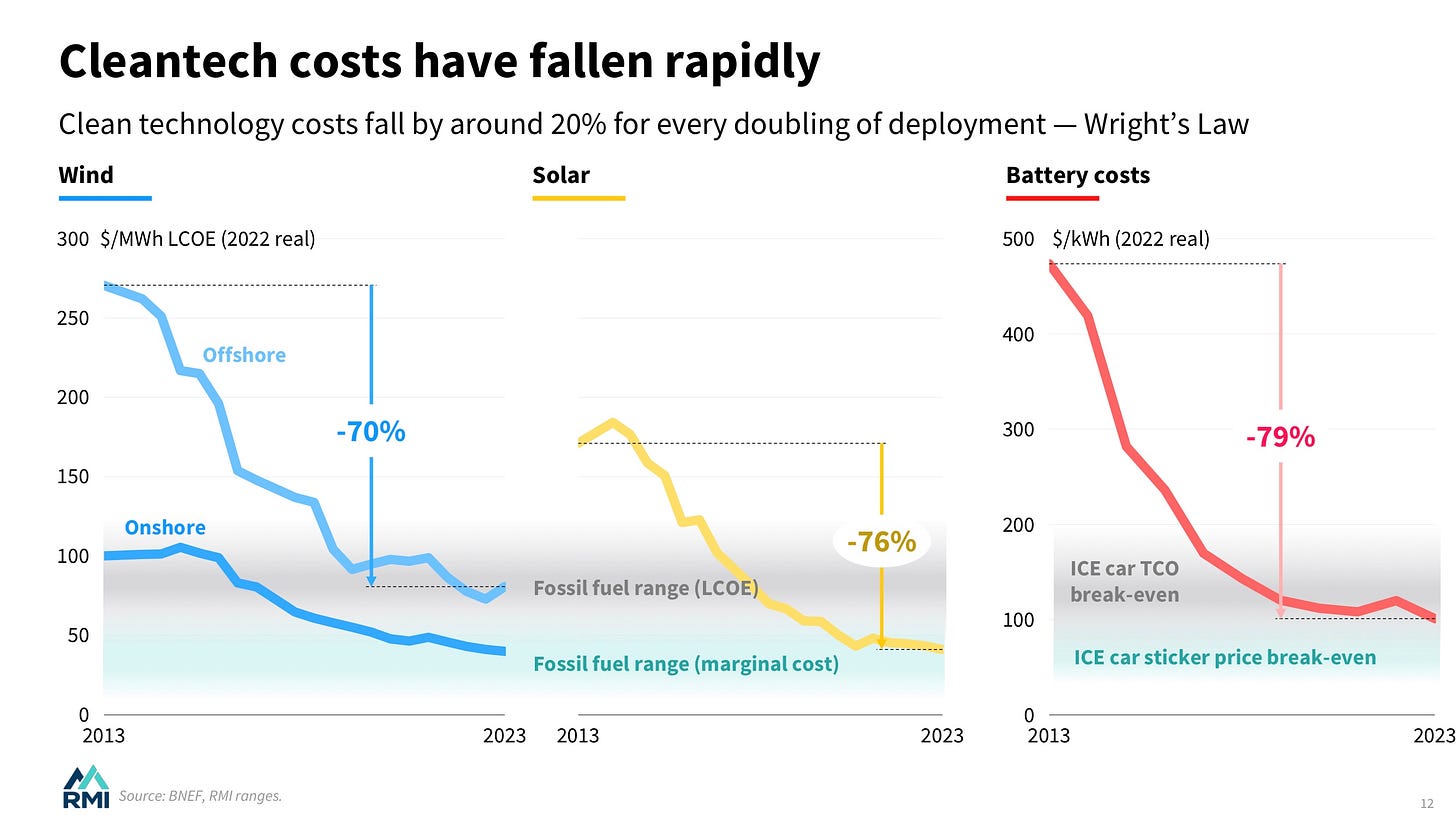

Electricity is where renewables have an edge — ever more so as the batteries that extend their use gain traction. That’s not the case instantly in all places for any purpose, of course. But it’s true broadly and ever more so over time, as the cost to install them continues marching lower and the benefits reveal themselves in greater efficiency and growing productivity.

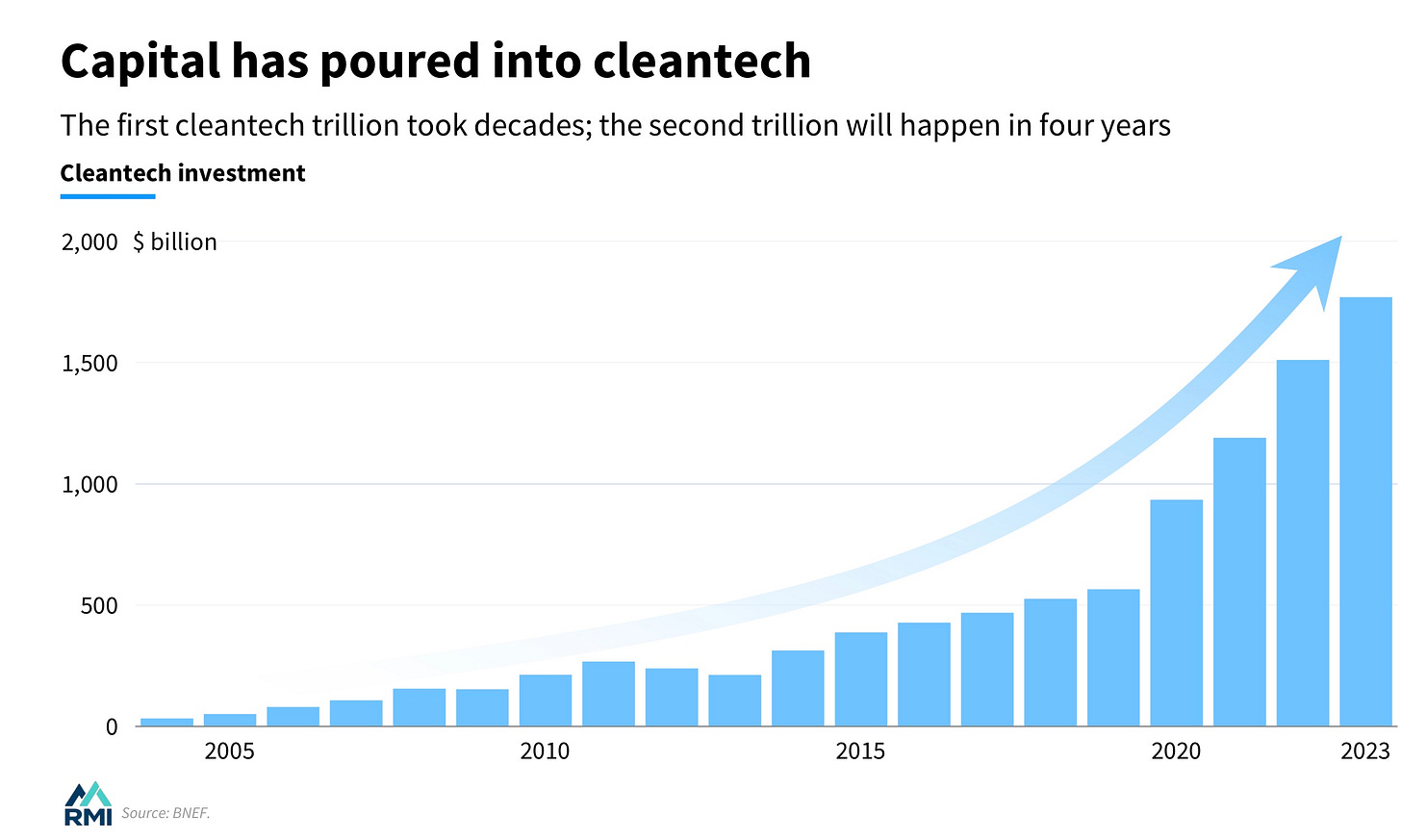

Wright drew cheers in Houston, as well as with an earlier speech to leaders from Africa gathered at the White House, by extolling fossil fuels. But a recent analysis by S&P concluded the U.S. will require between 60-100 gigawatts of new gas generation, and more than 900 gigawatts of renewables and battery storage, to meet electricity demand growth of between 35%-50% to 2040. That’s up to ten times more renewables, mostly because they can be stood up much faster than gas generation over the next five to eight years.

In developed and developing countries, in free markets and centralized economies, clean technologies are winning.

Texas, as free a market as can be, last year installed 80% more wind, solar and battery capacity combined than the next largest U.S. state. When I wrote about the Lone Star state’s surprising push into renewable energy for The Wall Street Journal back in 2016 (in this article), Texas officials were estimating that 19,000 megawatts of solar would be installed by 2030. The state already has installed more than that, with over 22,000 megawatts of capacity now.

Pakistan, whose military runs the show and leans heavily on Chinese-built coal plants for power, imported well over 13,000 megawatts worth of solar panels last year from China, equal to almost a third of the country’s total power capacity. Businesses and homeowners are fleeing soaring power prices on the coal-dominated electricity grid.

Now, in neither place will these additions obviate the need for fossil fuels soon — Texas uses a ton of gas and no small amount of coal, and Pakistan’s power still comes mostly from coal. And yes, the rapid growth of renewables is creating many new challenges for both places.

But here, as in many places, renewables are outcompeting fossil fuels much of the time. They will gain more share, as we’re already seeing in Texas, with more and more, cheaper and cheaper batteries deployed to extend their usefulness beyond the hours when the sun is shining or the wind is blowing.

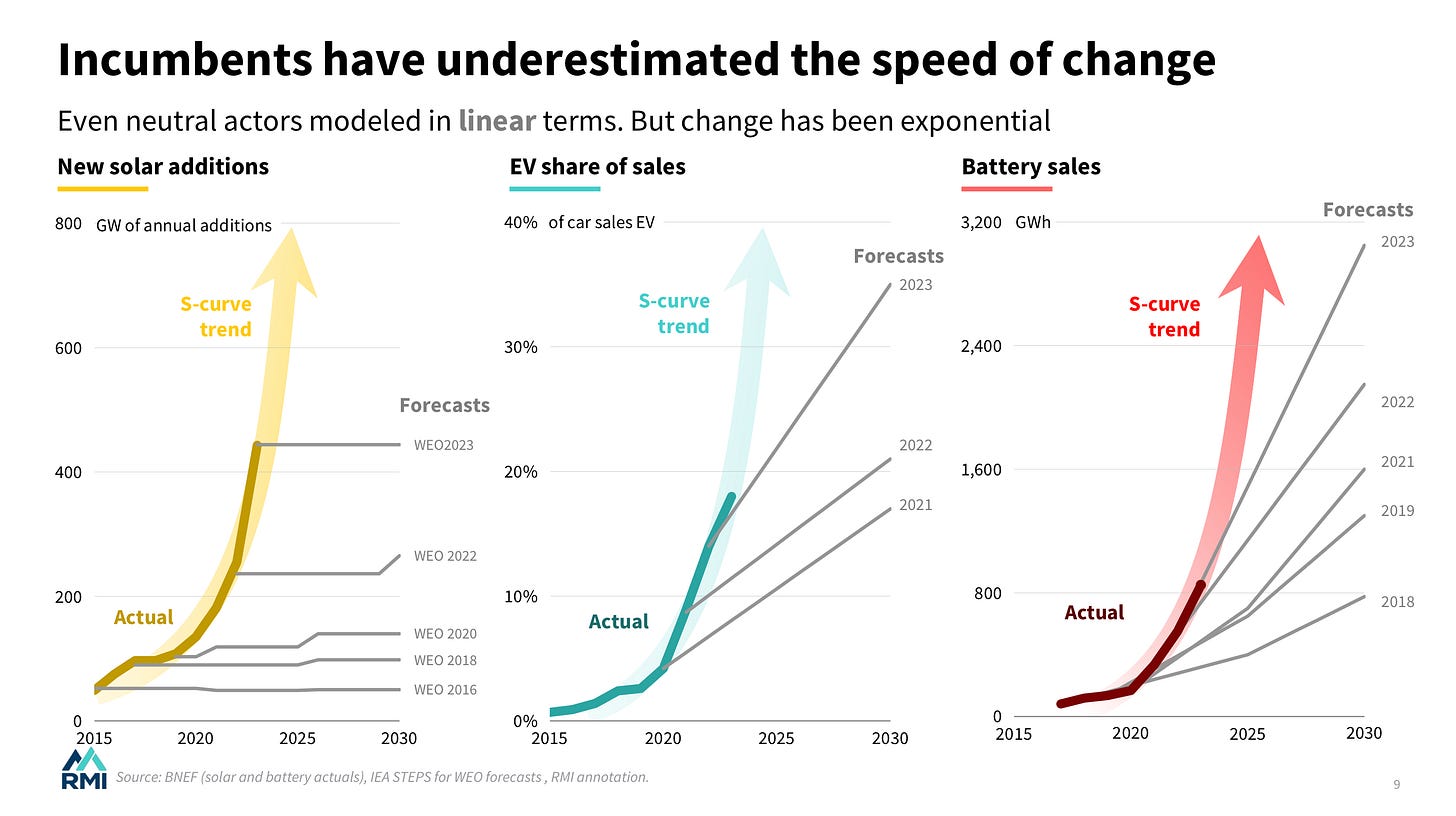

All of this is rattling the fossil-fuels based energy landscape, since each bit of electricity that doesn’t require combustion delivers far more results in terms of getting stuff done. This substitution of one renewable for what would in the past have been one fossil fuel won’t proceed in a linear, bit-by-bit way forever. It will eventually accelerate beyond meeting new demand to substituting renewables for existing fossil fuel generation, and at that point the transition will move even faster.

The separate turning points when coal, oil and natural gas buckle may well be followed by a more measured collapse than, say, local newspapers succumbing to the rise of digital competitors.

But my guess is it’ll be faster than many of those gathered last week at Houston’s CERAWeek expect, including Yergin and the authors of the Foreign Affairs article.