How The U.S. Can Help Itself By Helping India.

The Divide Between Developed and Developing Nations Shouldn’t Be Undermining Climate Talks.

Days before delegates gather for the most important global climate conference ever, countries are cleaving along familiar lines: the developed world versus the developing.

We’ve seen this before. As discussed in a earlier post, the rich-poor divide has been a bugbear of climate conferences from the beginning. It has torpedoed multiple agreements. Transcending it was key the successful Paris conference of 2015.

Indian officials thrust the divide onto center stage last week by highlighting, yet again and quite correctly, that the developed world has failed to make good on promises to deliver $100 billion in climate funds for developing countries annually by last year. A senior official in the environmental ministry went as far as calling the funds, aimed at transferring clean energy technology and adapting to climate change, reparations for damage caused by past emissions. African officials have said allocations from developed countries will need to roach $1.3 trillion by 2030.

Fair enough. The United States, which indeed is responsible for more of greenhouse gas emissions currently in the atmosphere than any other country, has made things worse by offering only meagre funds, despite the shortfall and the past promises. And the Biden administration has watched what was supposed to be its signature climate offering at the conference unravel on the eve of the conference. Developed countries admitted this week that they won’t crack the $100 billion threshold until 2023, but vowed to spend enough beyond that amount through 2025 that the average between 2020-2025 will exceed $100 billion. More promises.

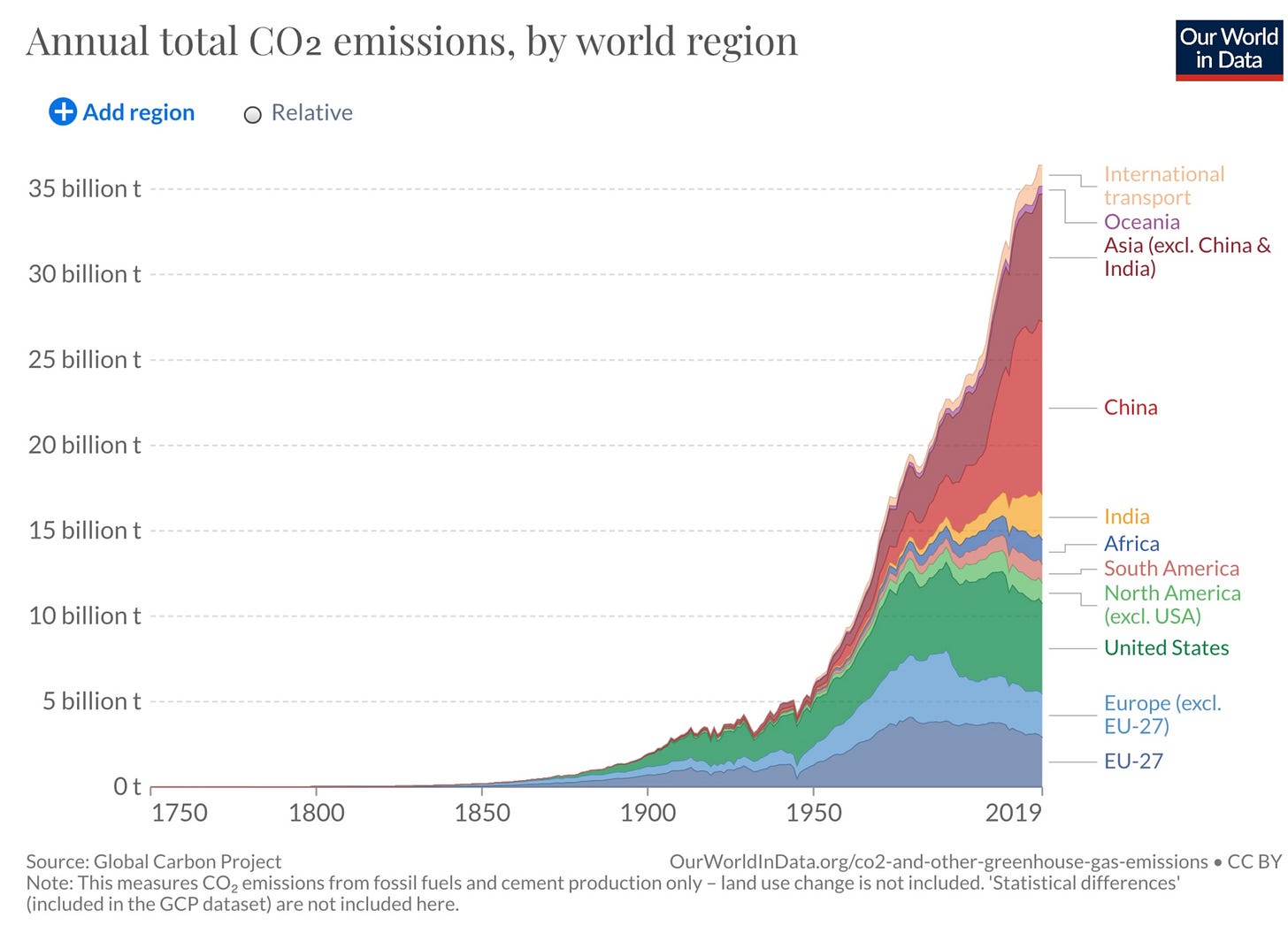

All this is a shame, since the logic underlying this long-running dispute has been turned on its head in the time countries have been arguing about it. One change has been well noted: the rise of China and, to a lesser extent India, into the ranks of massive emitters themselves. China is now the biggest emitter by far (28% of the global total), with India coming in third (7%), although both post far lower levels per person due to their large populations. As a country, the U.S., the biggest emitter at the first conference, now falls between the two at 15%, with just over double India’s share and half China’s. America’s per capita emissions still beat both.

Yet a far more important change is less remarked on: Falling renewable energy costs have made some renewables cheaper than any fossil fuel in many places, rendering the us-versus-them, zero-sum dynamic nonsensical. Or at least far less sensical, trending strongly in the direction of nonsense.

When renewable investments actually save money relative to fossil fuels, developed countries and rich investors can make money funneling investments into places like India. Meanwhile, those same investments save money for Indians, not to mention create cleaner air and an improved balance of payments as coal and oil imports fall. Working together is profitable for both the developed and the developing world. Paying for renewable energy is not a zero-sum game any more. And of course, emissions get reduced in the process — the main win-win.

Mutual benefits don’t stop there, either. And in this spirit I offer three other ways the U.S. could help itself by doing more for India:

Go well beyond the $5.7 billion the Biden administration offered earlier this year to contribute to the developing world climate fund. Biden recently upped that to $11.4 billion by 2024, though either amount would have to get approval from Congress. But go beyond even that to work with India to set up more loan guarantee and investment risk-mitigation schemes to unleash hundreds of billions more from private U.S. investors who would be eager to invest in India’s fast-growing renewable energy industry if the risks were reduced.

Find ways to purchase or otherwise create markets for some of the country’s output of solar panels, batteries and green hydrogen (including the eletrolyzers used to make it). India has ambitious plans to make and export these present and future mainstays of the green energy economy. Success would help provide the world with an alternative source of solar panels and batteries besides China, which currently has a vice-grip on those two industries globally. India’s attempt to make itself a solar panel manufacturing hub faces huge challenges — and the country’s manufacturing record has been underwhelming to say the least — but establishing a U.S.-friendly alternative to Chinese sourced panels is critical. Given India’s increasingly important role as a U.S. trade and security partner in Asia, the frontier of geopolitical power, working together on these fronts is a no-brainer. As the U.S. taps India for solar panels and batteries, the greening of India’s power grid could re-open the door for U.S. automakers to hawk electric vehicles in market that would likely tilt in their favor against stiff Chinese competition.

Drastically accelerate efforts to reduce the U.S.’s own greenhouse gas emissions. This, of course, would counter arguments from India and the rest of the developing world that the U.S. isn’t doing enough. And, of course, it would help mitigate climate damage in the United States, which spent the summer battling wildfires, hurricanes and droughts in which climate plays a major role. But there’s another way it would help the U.S. by helping India: heading off even worse climate impacts on the subcontinent, which is far more vulnerable than the U.S. and other developed countries. A recent report by Deloitte, the global consulting firm, argues India would lose about $35 trillion worth of potential economic growth over the next half-century if the world stays on its current emissions course. Rapid global decarbonization, on the other hand, helps India India gains $11 trillion in growth by 2070. That’s an astonishing swing of fortune, and one the U.S. could have a meaningful impact on by simply doing what’s good for itself. Which future India would you rather team up with? Which would be the better long-term purchaser of everything from U.S. arms to electric vehicles and more effective counterweight to China in one of the most contested areas of the high seas? The less distracted India is tackling climate change impacts, the more it can be that partner.

Nothing better than reading something that makes you stop and think. Mission accomplished Bill!