The Ups and Downs of a Planned City

India’s most ordered city offers some lessons, but not solutions, for today’s nation.

Don’t forget to subscribe to the global climate and energy newsletter I’ll be launching as part of Semafor, an ambitious new news organization I’ve joined. We launch soon. Sign up here.

Clean lines. Sharp edges. Platonic forms.

This is India? Well, sort of.

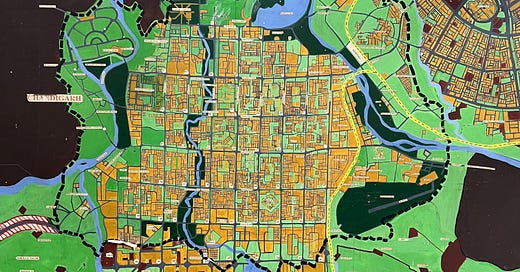

Squaring the oh-so-orderly city of Chandigarh with the sprawling, chaotic, bursting-with-life urban spaces in the rest of India is no simple task. The dual capital of two states — Punjab and Haryana — Chandigarh is at once the country’s most deliberately planned city and one that exists altogether apart from India today.

Chandigarh was conceived by independent India’s first leader, Jawaharlal Nehru, as a futuristic, utopian experiment in the aftermath of the violent partition that created two nations from Britain’s Indian empire in 1947. With Lahore, the capital of the Punjab region under British rule, ending up in Pakistan, India needed a new state seat for the Punjab region that remained behind.

The new capital was planned, and its construction overseen, by Westerners: the Swiss-French architect/designer/urban planning giant Charles-Edouard Jeanneret, better known as Le Corbusier, and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret. They were contracted in 1950 by the Nehru-led government.

My wife and I spent a week in Chandigarh, which had somehow eluded my widespread travels throughout the country during the four years I was posted there with The Wall Street Journal. The city is everything the rest of India’s urban spaces are not — organized, open, attentive to its public spaces, full of trees and only mildly burdened by traffic congestion.

There are many lessons the rest of India could take from Chandigarh’s meticulous city plan and the strict municipal zoning enforcement that assures its preservation. As the head of the city’s environmental department pointed out, almost no other cities are seeing population and automobile ownership rise at the same time they are increasing the area devoted to open space and parkland.

City leadership has worked particularly well with the population to inculcate pride and engagement in preserving and improving on parks and green spaces. During early morning strolls around the city, I found the city’s numerous parks full of joggers and walkers, yoga practitioners and badminton players.

While the rest of India relies on dirty coal for nearly three-quarters of its electricity, Chandigarh is aiming for 100% renewable electricity provision by 2030, Debendra Dalia, the environmental department chief, told me. That’s achievable in part because of the availability of hydropower from dams located nearby in the Himalaya mountains, which are visible from Chandigarh. But the municipality is also making strides installing rooftop solar, not only on government and office complexes but also residential buildings.

That’s the result of generous net-metering policies, allowing households to sell power back into the electricity grid when their panels generate more than needed. The public transport system is changing over to electric buses gradually, and there are plans to install 100 charging stations for electric cars in the next two years.

Yet ultimately the lessons Chandigarh has for the rest of India are limited. The city’s population has grown dramatically along with the rest of India, of course. Some 1.2 million live there, up from the 150,000 original residents the city was designed to accommodate.

That growth, however, doesn’t account for even more rapid population expansion outside the boundaries of the planned city. Yet this is where many of the administrators, bureaucrats and every day workers that make Chandigarh tick live. In that sense, the city has managed to simply wall itself off from the growth challenges most Indian cities face, while still drawing the benefit of the labor pool from those peripheral areas. In other words, Chandigarh is displacing problems rather than solving them. The most obvious example is the lack of a regional rail or subway system — long resisted by the city’s wealthy residents, even as their economy depends largely on workers from outlying areas.

This is why other metropolitan areas have taken the lead in wrangling with the full and daunting challenges that rapid urbanization and climate change present for Indian cities. We’ll visit two of these in future posts, the western city of Surat in the state of Gujarat and the southern city of Chennai in Tamil Nadu state.

Both are increasingly exploring more flexible, so-called “nature-based” solutions that attempt to both accomodate the expansion of India’s urban population and address the growing threats from climate change.

very late to this but wanted to comment that James C. Scott writes extensively about Chandigarh (and other planned cities like Brasilia) in his opus Seeing Like a State (the third chapter, I believe?). He's relatively critical but very good on what kinds of power planned cities serve. I haven't spend much time in Chandigarh but have always found it peculiar to navigate - interesting to thin about how that interfaces with climate crisis.