The Leapfrog….

Developed and developing countries are on two different energy transition journeys, hopefully leading to the same place.

The global energy transition from fossil fuels to renewables is off and running, albeit with a long ways still to go. Less appreciated are the starkly different routes this historic shift is taking in the developed versus developing worlds.

India is very different from the United States or Europe. So is India’s approach to energy transition. The many reasons for this boil down to one thing, growth. India’s thirst for modern energy only been whetted; in the coming decades demand will perhaps triple. U.S. and EU energy demand likely won’t grow, and might even decline.

This means the challenge for the U.S. and Europe is replacing their existing fossil fuel-based energy system, pushing a unit of energy derived from coal, gas or oil right out of the system with the insertion of energy from new green sources. For India and the developing world, the challenge is different: how to add green energy fast enough to get ahead of ballooning demand and avoid building out a system dependent on fossil fuel that will be increasingly expensive and obsolete.

Think of it like this: The U.S. and Europeans are basically renovating a home after the kids have flown the nest. This is an expensive and sometimes difficult process of uprooting the old, throwing out many things you love (or are at least have grown used to), and deciding on what’s best going forward. For the developing world, it’s more like the thrill of building a new house — fun and in many ways easier than renovating until you realize selling, or even tearing down, the old house isn’t immediately possible. No one wants to buy it. Even more important, turns out you also still need it to meet the needs of your family, what with young, growing kids needing all that additional food cooked, light to study after dark, a fan if not AC, and power for their computers, phones and scooters. Oh, and you don’t actually have the money banked to build that new home. You’ll have to finance it.

For a long time, both these tasks — for the rich renovating, for youthful up-and-comers building a new home — seemed obligatory if you believed climate change is real and needs addressing. But they weren’t really worth it in a narrow, self-interested economic sense. Hard-to-estimate future climate damage aside, both undertakings used to cost more than they’d save, even over the long run. Better to put it off, hoping your neighbor went ahead so you could benefit without the expense.

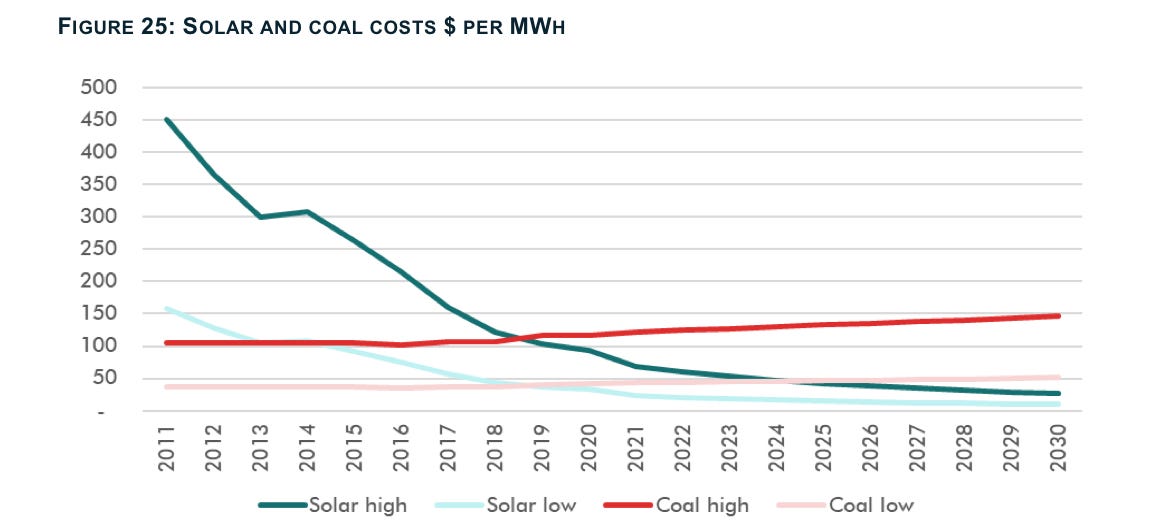

This dynamic has been upended by cost declines in renewable energy, particularly solar, which is now the least expensive energy source in much of the world. Behold the green line below piercing first the red and then even the pink line as solar undercuts first new coal-fired generation and then even coal that’s already up and running. In fact, in India and much of the developed world the lower threshold has already been shattered. When available, solar is the cheapest source of energy. And solar is available for tapping far more than is presently happening. India and Africa, for example, have great solar resource; the sun shines a lot. The developing world, ex-China, is only deploying renewables to provide about 4% of electricity supply, according to the report, while some developed markets are at well over half. India is at about one-quarter. Over time, as battery costs fall and techniques for shifting demand to when solar is available spread, more solar will be available to meet more demand.

As a result, both renovating the old house for the empty nesters and getting going on a new one for the younger set are clearly worth the effort, in every sense. The world can now do well by having done good. The challenge is how to get from here to there faster than any energy transition in human history — since that’s what we’ll need.

For the developing world, that way is to leapfrog.

We’ve seen it before. When mobile phones became cheaper than landlines, Indians without phones jumped straight to mobile. And with the internet: In the past five years, much of the Indian population skipped desktop computers and went online with a smart phone, even if it was a rudimentary, dirt-cheap one. Many Indians made both leaps at once, buying their first phone and getting online at the same time in a kind of two step.

Now comes energy’s turn. For some of the least developed countries, including many in Africa, that means leaping from burning dung and twigs for energy right over coal and gas fired generators to draw power from rooftop or village solar systems. For countries further along the development spectrum, like India and Vietnam, the leapfrog is more like a half a leap, from the existing coal-based power system to standing up a green system going forward as much as possible until demand growth slows or renewables gets easier to add and the old system can be phased out.

Carbon Tracker, a U.K.-based advocacy group, and India’s Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW), recently offered the most detailed picture yet of what a developing world leapfrog looks like, and why it matters. They focus on renewable electrical power generation, the first and biggest energy leapfrog because it will provide the foundation for electrifying much of the rest of the fossil fuel-based economy, from transportation to residential heating and cooling.

They point out that:

88% of the growth in electricity demand to 2040 will likely come from emerging markets.

Emerging market growth will be split roughly between giant China (39% of growth), other coal and gas importers like India and Vietnam (50% of the growth), coal and gas exporters like Russia, Saudi Arabia and Indonesia (10% of growth) and countries like Iraq and Nigeria that don’t have the wherewithal to transition without external support (even if it benefits them to do so).

In many of these emerging markets, fossil fuel demand has already peaked. Indeed, overall fossil fuel use for electrical power in developing countries other than China may have peaked way back in 2018, the report argues.

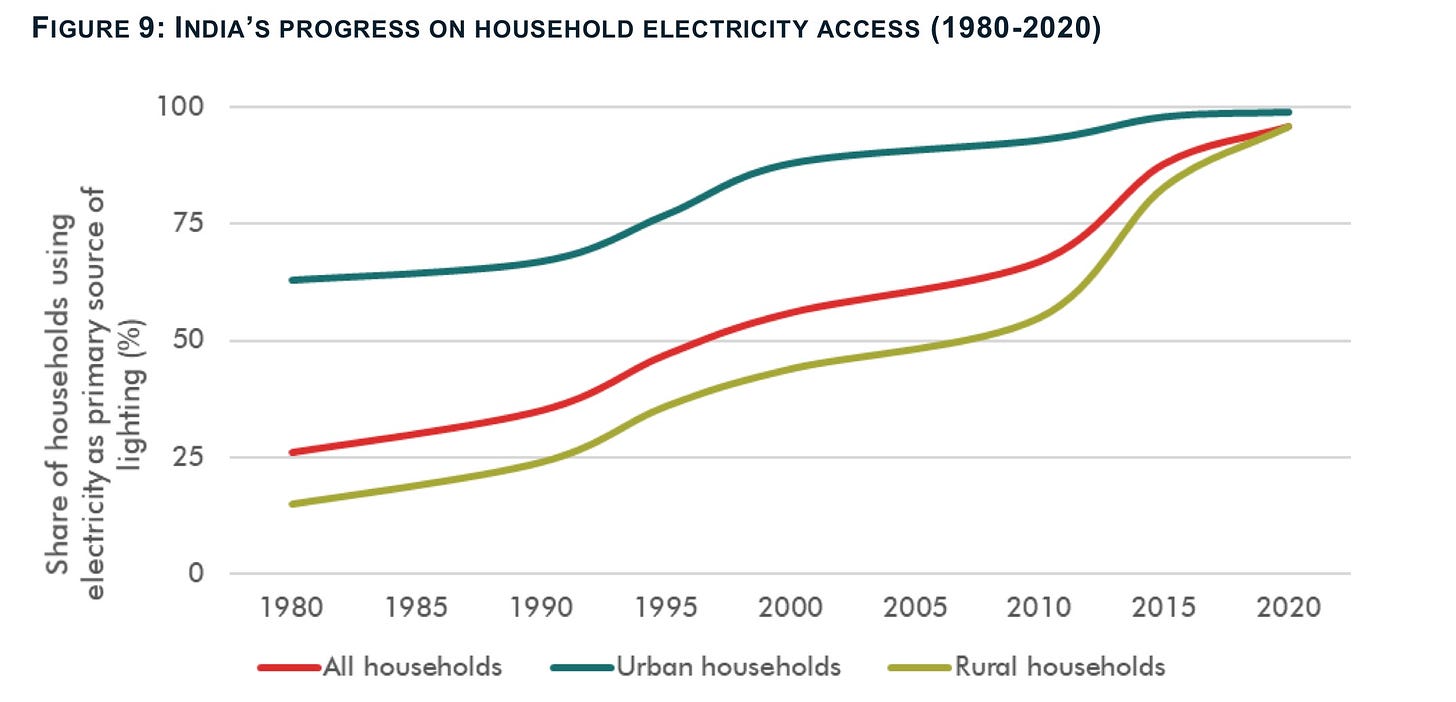

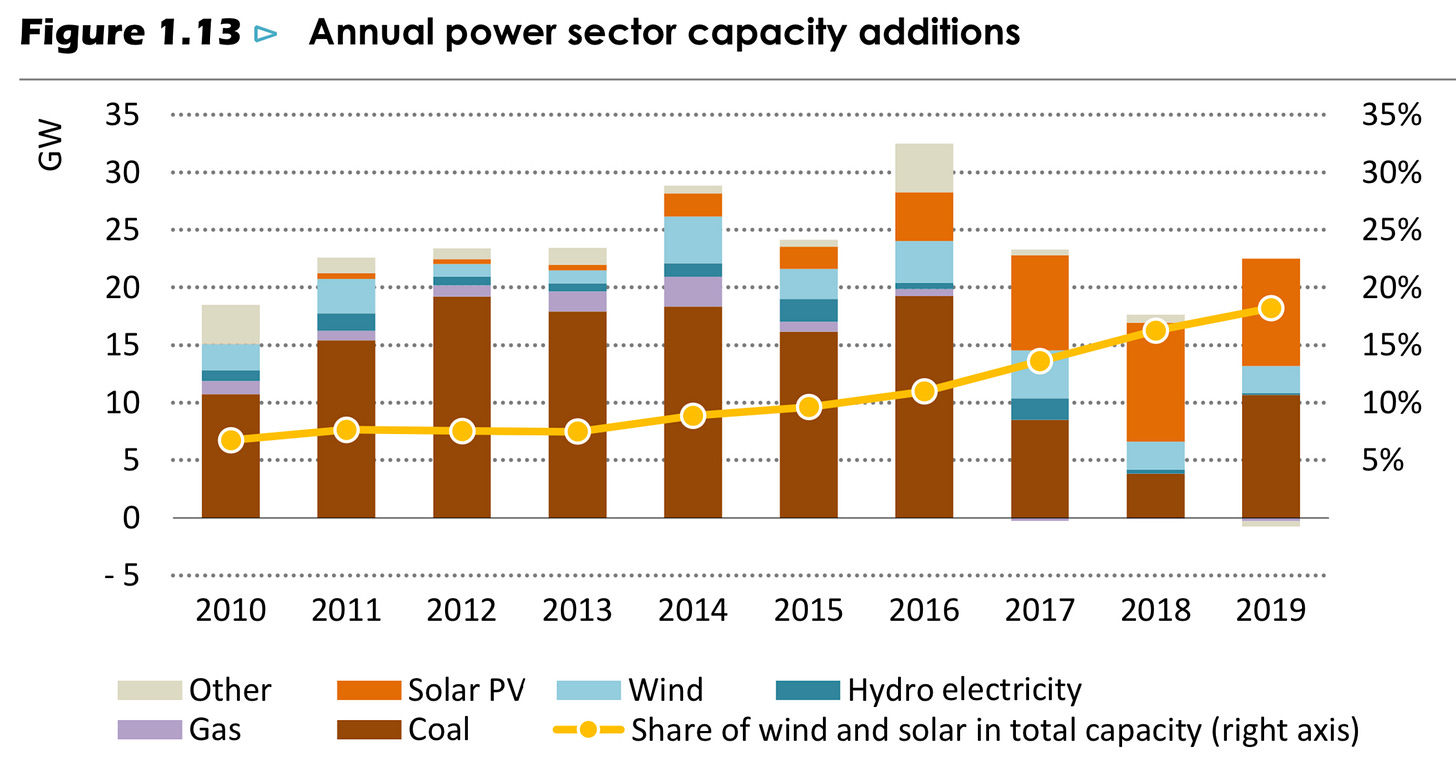

India has pulled off in two decades a feat unmatched in history: bringing first-time electricity to some 800 million people — more than double the population of the U.S. — while building out renewable capacity equivalent to the needs of 30 million U.S. homes. In other words, India has vastly expanded its electricity system while slowing down its building of new coal-fired plants, indeed contemplating ceasing their construction altogether.

It’s worth illustrating that last bullet point with some graphs:

Here’s India’s progress bringing electricity to its population:

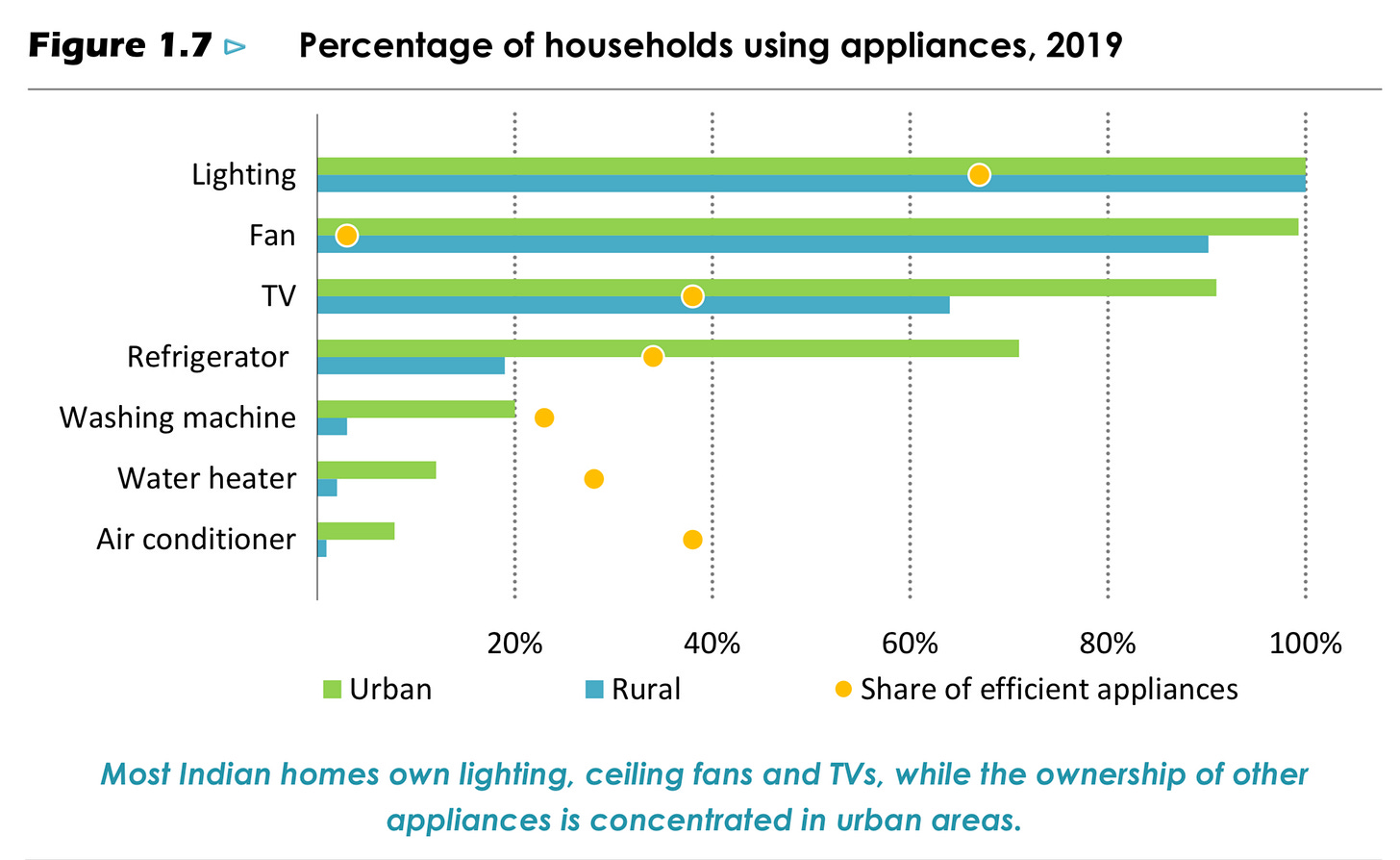

Here’s how that electricity is being used (still mostly for the basics, but you can see where the trends are heading as the middle class expands):

And here’s where that electricity is increasingly coming from, especially since 2013 (the widening orange solar ban):

The upshot of the report almost goes without saying, but let’s do it anyway….

“Without an emerging markets leapfrog there will be no energy transition,” concluded Kingsmill Bond, an analyst with Carbon Tracker, during a panel discussion launching the report.

The challenge now is how to speed things up.

Developing countries’ historical emissions account for little of the total of greenhouse gases accumulated in the atmosphere to date, but those emissions are threatening to explode going forward. China’s already have, and it’s the world’s biggest emitter. The rest of the developing world has to focus on assuring this doesn’t happen to them. This doesn’t mean restraining demand by denying energy access to the poor — their initial energy demand will be tiny — as much as preparing for their inevitable rise into the middle class. That’s when their energy consumption will grow exponentially.

Less than overhauling its old house in a drive straight for net zero today, India and the rest of the developing world must focus on building a robust decarbonized energy system for the future day when that moment unfolds. Or we’ll all pay the price.