In this post, let’s dig into critical minerals.

The first thing to understand is that they are, well, critical.

They’re critical for the energy transition. That’s why I traveled to Chile to have a look at several mining sites, one more than a mile high in the Atacama Desert of the Andes Mountains, the other along the Pacific Coast near the industrial city of Concepción.

But they’re also critical for many other things. They’re an indispensable ingredient in semiconductors, the foundational technology for nearly every device and gadget in modern life. At the cutting edge, they’re the all-important facilitator of artificial intelligence. Critical minerals are critical for making drones, which are transforming not only many industries but also modern warfare. That makes them the key to missile guidance systems, satellites, radar arrays, defense shields, super-hardened armor and the advanced F-35 fighter jet, centerpiece of U.S. air power.

In short, critical minerals are critical for any country competing for advantage in the increasingly cut-throat game of international economic and military dominance.

That’s why President Trump has been fixated on obtaining them. They explain some of the appeal of Greenland and Canada, and his obsession with getting Ukraine to agree to hand over any critical mineral deposits beleaguered nation may have.

Trump, of course, is far from the only world leader obsessing about critical minerals. Nearly every country is preoccupied with them, whether because they need them or have them. That’s been especially true since 2010, when China underscored their potential as a national security tool by cutting off some critical mineral exports to Japan during a maritime border dispute.

No nation is more obsessed than China. Over decades, the country has come to mostly or wholly dominate every step in the process of obtaining critical minerals and putting them to use. The U.S. has realized it must change that, as a matter of national security.

And here lies a tangle of the Trump administration’s most paradoxical policies. The paradoxes they embody put at risk his goal of making America great again — at least if building the strongest economy and the most powerful military is what that means.

President Trump wants to establish U.S. dominance, or more realistically at least self-sufficiency, in critical minerals. Yet he appears determined to snuff out the very industries utterly essential to make that happen. These are the clean-tech enterprises that will provide most of the demand growth for these minerals: electric vehicles, batteries, advanced electrical transmission grids, wind turbines, solar panels and nuclear fusion, among others.

Without playing in those industries, the U.S. will not be able to compete in, much less control, the critical minerals game. We’ll have little choice but to keep relying on others — mostly China — for the processed, refined critical minerals we need for other purposes, like defense and artificial intelligence. Or, more clearly stated, we’ll rely on China only to the extent China indulges that dependence.

A less than ideal state of affairs, particularly when you’re antagonizing China with tariffs.

So what exactly are critical minerals? And why can’t we just mine them ourselves strictly for what we most need to defend ourselves and promote our security interests in the world?

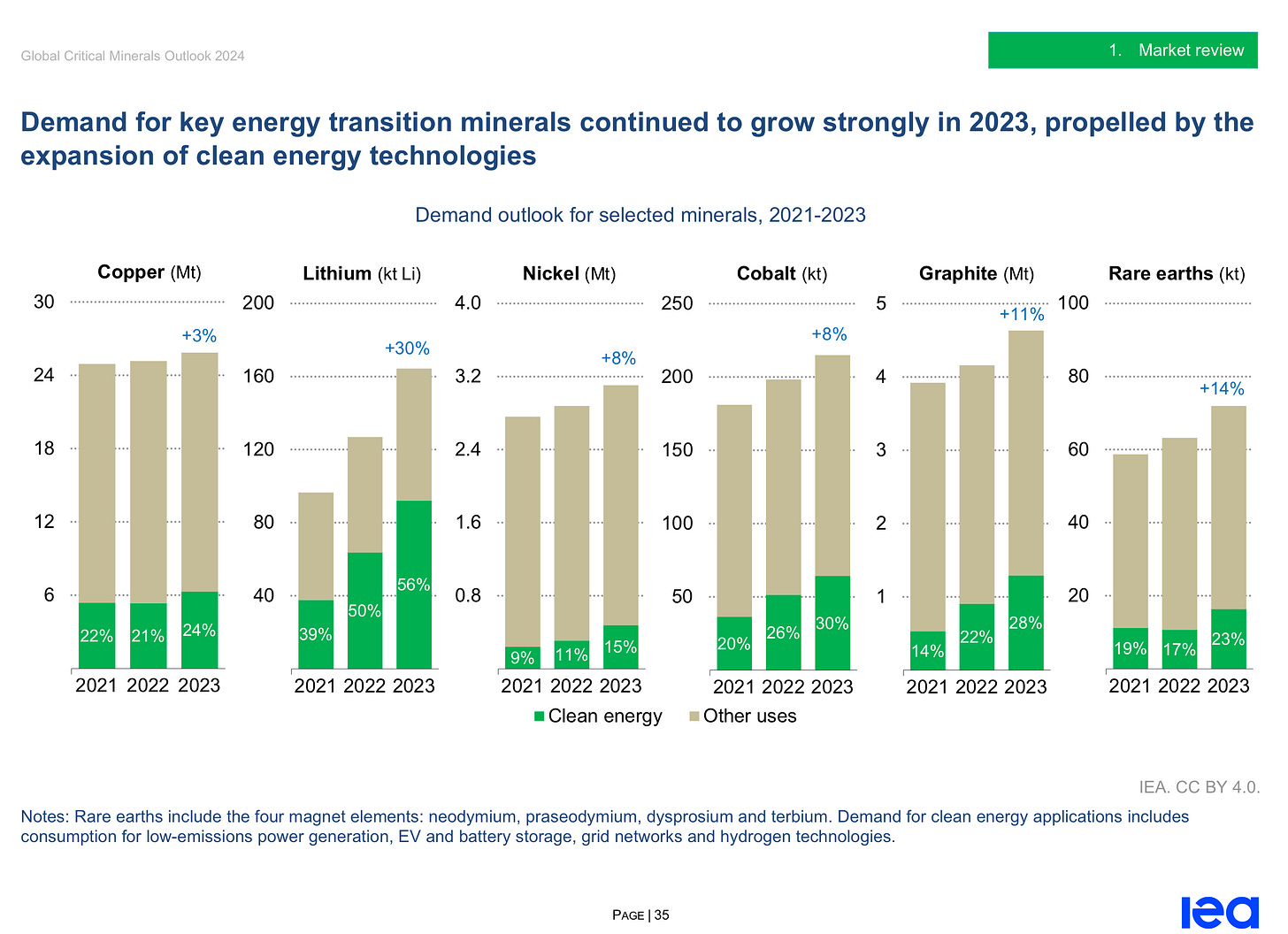

Critical minerals range from the commonplace to the exotic. They include trusty old copper, needed for every electric transmission wire and machine that requires electric circuitry, including traditional gas-powered cars. Lithium, less known, is used in nearly every battery today, from iPhones to drones. Nickel and cobalt are other minerals key to making batteries, as is graphite.

Then there are 17 elements known as “rare earth” metals, a collection of tongue-twisting entries on the periodic table you learned about in high school chemistry class.

They include neodymium (Nd), praseodymium (Pr), dysprosium (Dy), and terbium (Tb). They are used to make the super powerful magnets used in everything from handheld vacuums to electric vehicle motors to nuclear fusion reactors. There’s also promethium (Pm), used in specialized batteries, samarium (Sm) for lasers and Europium (Eu) for LED lights, television screens and computer monitors. Heavy rare earths, such as Gadolinium (Gd), are used in MRI machines and Erbium (Er) in fiber optic cables.

Critical minerals, even rare earths, actually aren’t that hard to find. Mining them commercially is far harder.

In Chile, I looked at two different ways in which it is hard. The first story, about a lithium project 14,000 feet high in the Andes, looked at the challenges miners of critical materials face with local communities affected by the mining. The second story, about a rare earth minerals project, looked at some of the environmental challenges — and regulatory concerns — involved in mining.

Once extracted, critical minerals then have to be refined and processed, another challenge that runs the gamut from dirty and dangerous to delicate and demanding.

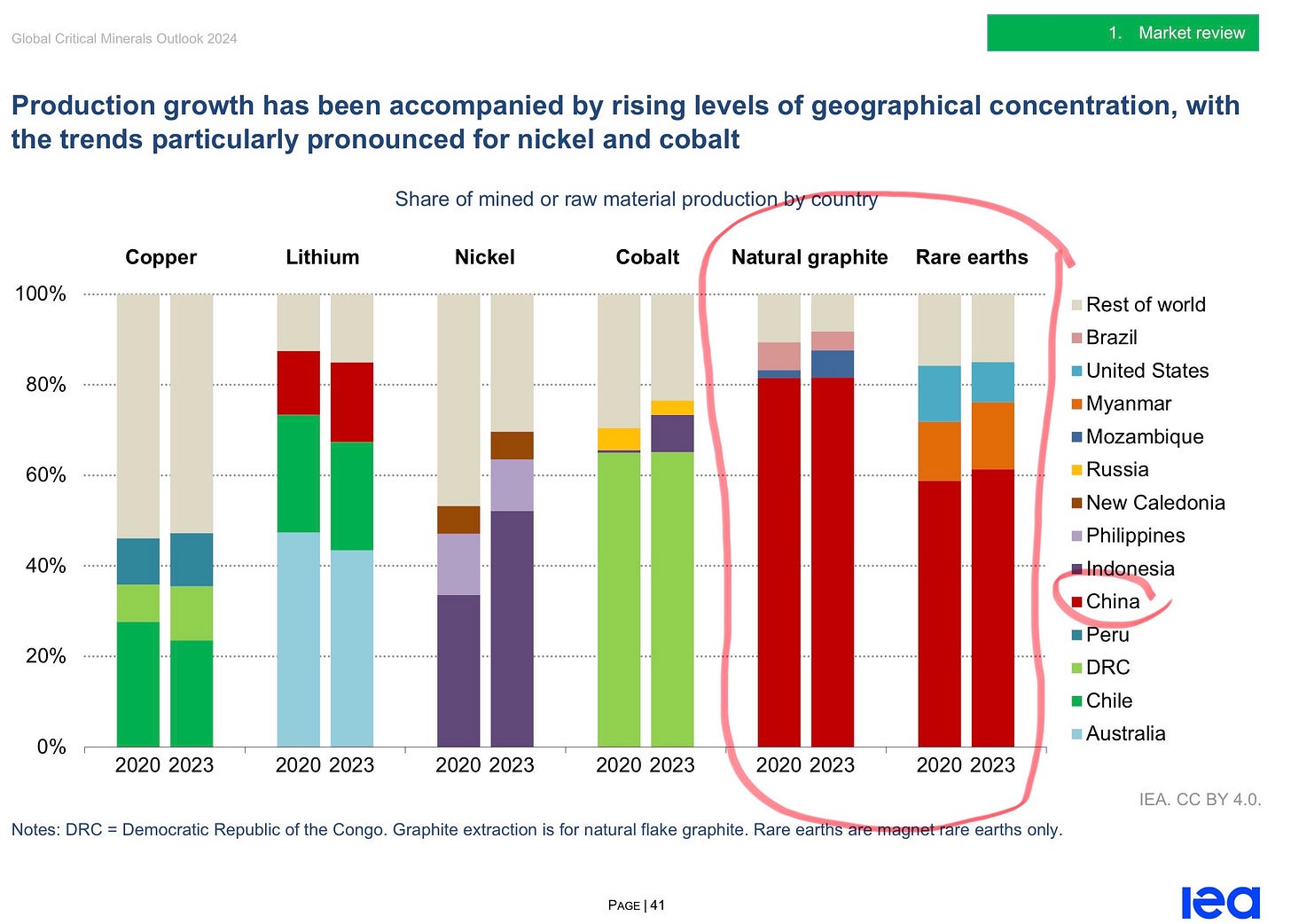

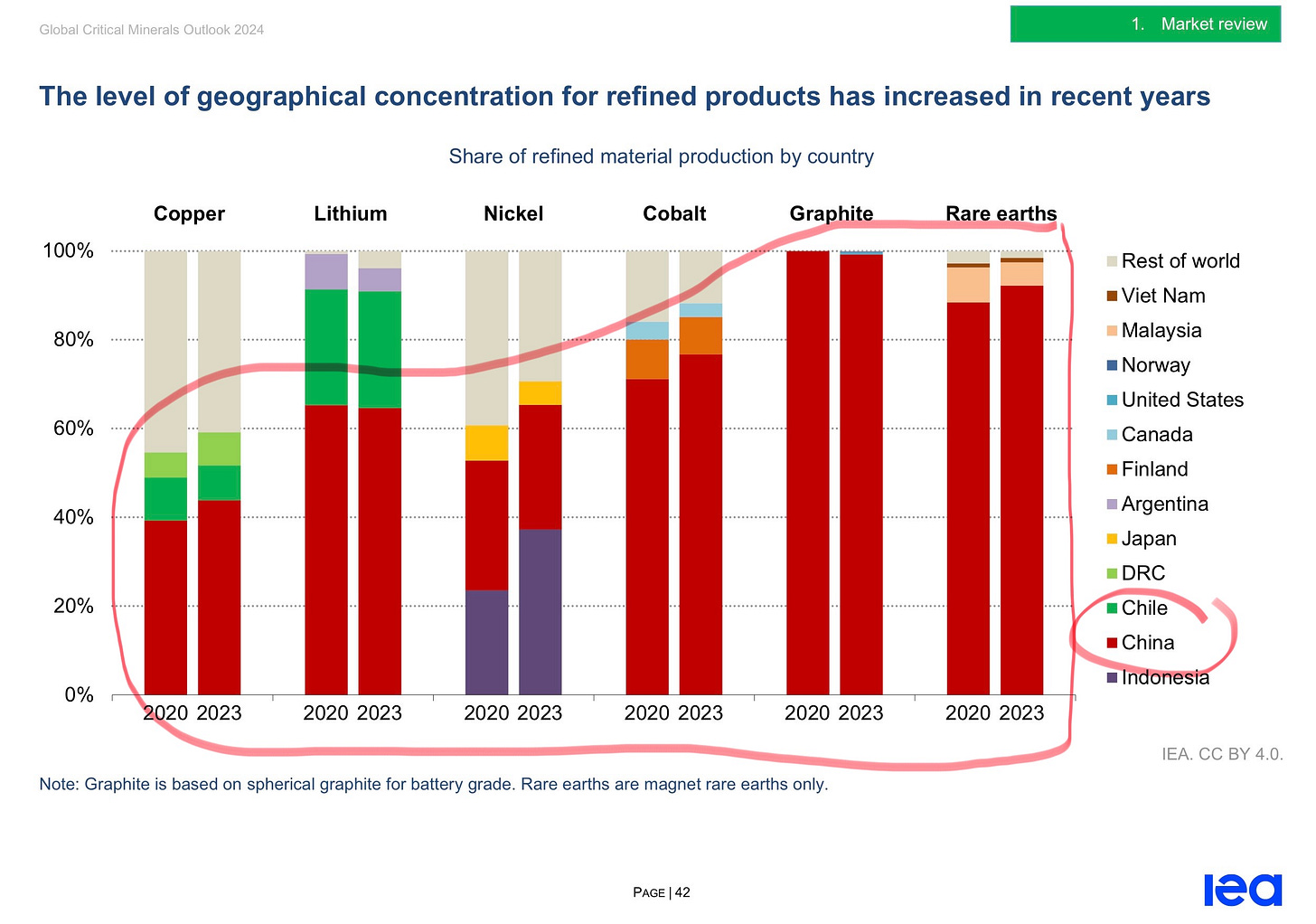

China lords over nearly every aspect of this global critical minerals extraction and processing. These charts from the International Energy Agency illustrates how stark the situation is:

What does all this have to do with the energy transition?

Fossil fuel advocates and transition skeptics argue that moving from fossil fuels to renewable energy will only create a dependence on China for critical minerals. Better to stick with the gas, oil and even coal, which we Americans can obtain right here at home, they say.

But we’re already dependent on China for critical minerals, at least to the extent we want to keep our military and defense strong, our economy humming and our artificial intelligence industry advancing.

Of course, as I said, critical minerals are actually quite plentiful, including in the U.S.. Arkansas and Nevada have lithium reserves. Wyoming has deposits of rare earths. We can try to meet our needs without China by working with allied countries or even, I suppose, taking over Greenland and snarfing up Canada.

There’s technically no reason those minerals couldn’t also be refined and processed in the U.S. — other than the need for a workforce willing to take on the job and communities willing to host it.

But all that is expensive. It requires large, growing sources of demand for critical minerals to pay for it — much larger and faster growing than defense or existing U.S. industry will provide in the coming decades.

China has solved this problem by diving into clean energy manufacturing industries with both feet — business and government. The nation largely has leapfrogged internal combustion engines to build an electric vehicle industry, which is now rapidly expanding globally at the expense of U.S., European and Japanese automakers. That rapid expansion is driving a huge surge in demand for batteries, which Chinese companies excel in making. It sprouted hundreds of solar panel manufacturers and wind turbine makers, in which Chinese companies lead the world.

China’s clean-tech industries now dwarf those elsewhere. The country’s solar panel manufacturers have enough capacity to meet all global demand to 2030, even as the nation installed more solar power last year than every other country combined. China currently accounts for close to half of global electric vehicle sales, allowing it to dominate the production of the batteries that go in them.

This chart from an analysis by a task force at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace tells the story:

These industries are making outsized contributions to China’s economic growth. Their fast-expanding demand for critical minerals is the muscle behind the country’s iron grip on global markets for critical minerals. Indeed, this domestic demand is why Chinese critical minerals suppliers can undercut competitors that must compete with global price levels set by the Chinese processors.

Of course it would make little sense to build an uneconomical clean energy industry in the U.S. solely in order to subsidize the production of critical minerals for national security and other reasons, however critical they might be.

But it makes no sense at all to crush, or even disadvantage, industries such as solar and wind power, electric vehicles and geothermal energy that are clearly emerging as important elements of modern energy systems. They can provide the critical mass of demand necessary to support the extraction and processing of critical minerals. They are also hotbeds of innovation that offer U.S. entrepreneurs and manufacturers — indeed the whole U.S. economy — a chance to beat China’s technologies with even better ones to get ahead again.

That’s what makes these clean-tech industries…well, critical.

Bill: I love your article!! I've been following several other articles lately that point out why this is important for our future -- we're way behind China!

Best of all, it makes me very happy that YOU are contributing to our world each and every day!

Ah, good education, good writing --- good person! My best to you, always!

Joyce (Judy's friend)

As always, thank you for keeping us informed!