My chat with Bashar al-Assad

The nightmare is over. But Syria’s challenges are many, including climate change.

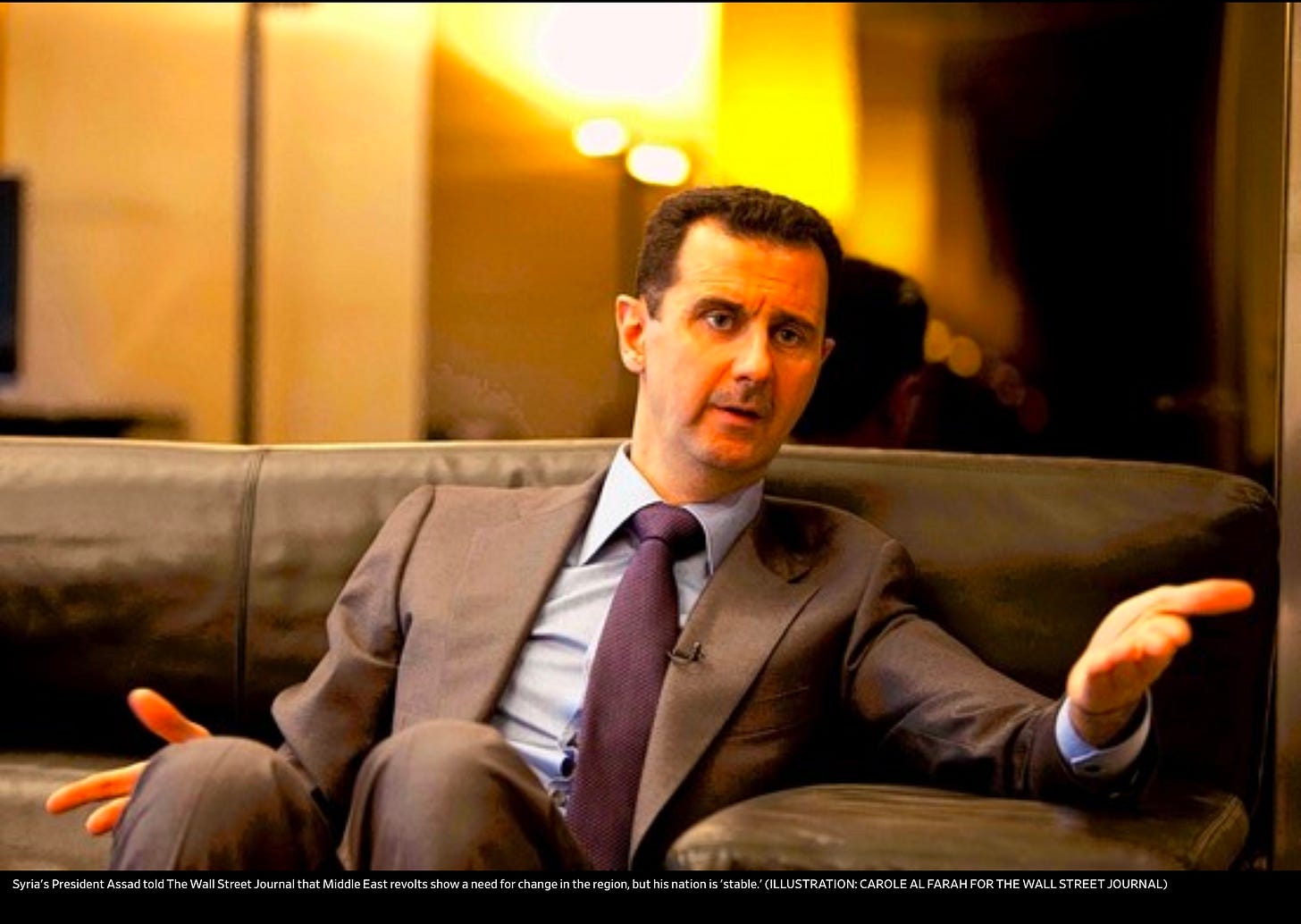

Nearly 13 years ago, a Wall Street Journal colleague and I sat down for a chat with Syrian President Bashar al Assad, whose family by then had ruled the country with an iron fist for four decades.

We discussed the popular uprisings beginning to sweep the region then, what would soon become known as the Arab Spring. As Assad, dressed in dapper suit and tie, amiably opined in a comfortable office overlooking Damascus, a television across the room broadcast raucous scenes from Cairo.

Demonstrators were flooding Tahrir Square in protest. Things were not going well for Egypt’s president, Hosni Mubarak. (within a month he would be forced from office). Assad was gloating over all of this. He expressed disdain for Mubarak, blaming the protests on Egypt’s diplomatic ties with Israel. What did the protests mean for the region, we asked him?

“Is it going to be a new era toward more chaos or more institutionalization? That is the question," he told us. "The end is not clear yet."

As for Syria, it is “stable,” he told us. “Why? Because you have to be very closely linked with the people.”

Or not, as it turned out.

Within a year, protests began there as well. Syria spiraled into a civil war that festered on for more than a decade — until this month. For Assad and his family’s venal, vicious rule, the end is clear.

They are exiled to Russia. Syria is held by rebel groups. Assad’s question for the region can now be asked about Syria itself: will there be institutionalization or more chaos?

And, for our purposes here at The Energy Adventure(r), what does any of this have to do with climate change?

The short and flip answer, of course, is not much. The Assad family’s domination of Syria ground to an end because from its inception the Syrian state existed to nurture the power of the Assad family and, ultimately, as it weakened, the outside interests that kept it in power: Russian and Iran. The people of Syria — a disparate collection of the Middle East’s historic melange of Sunni, Shiite and Ishmaeli Muslims, Christians, Druze, Alawites, Palestinians, Kurds and secular nationalists— mattered hardly at all.

In the end, all of them wanted the Assad family gone — even if some deeply fear what might follow. I’ll leave the analysis of what happens next to those who have more recently followed the alphabet soup of militias and fighting factions, along with their regional and global backers (which include nearly every major global and regional power other than, arguably, China).

The end of Assad family domination opens a new and potentially positive new era for Syria and a land whose history stretches back to the beginnings of human civilization. For the Syrian people, there’s almost nowhere to go but up — though the Middle East routinely has managed to prove sentiments like that wrong. For the surrounding region, chaos could easily prove worse than the Assad rule in its heyday and perhaps even than the last decade of quasi-collapse.

And that’s where the longer answer to the climate question matters, and resonates far beyond Syria.

Climate didn’t cause Syria’s convulsions. But the gross mismanagement inflicted on the country by Bashar al Assad — and his father before him — did not have nothing at all to do with climate change, either.

Climate didn’t cause Syria’s convulsions. But the gross mismanagement inflicted on the country by Bashar al Assad — and his father before him — did not have nothing at all to do with climate change, either.

As I’ve noted here in the Energy Adventure(r), the government’s abject failure to address the creeping desertification of the country’s north over decades devastated rural farm communities in the north. Displaced farmers were not the instigators of the protests, much less the full-on violent uprising against the Assad regime. But it was in these regions that the resistance gained a lasting foothold and forged a base from which it ultimately brought down the regime.

The Syrian state’s failure — unwillingness, really — to address fallout from the region’s always-difficult climatic conditions was partly to blame for its demise. It will fall to whatever government that now follows to meet the even greater, and growing, challenges climate change is bringing to the country and region.

The Middle East and North Africa is among the places most vulnerable to climate change on earth. Temperatures are rising faster than the global average, and the impacts are hitting the still-largely rural economies of the Levant, which includes Lebanon as well as Syria, and southern and Eastern Turkey. Drought is a chronic problem — not only for agriculture but also for cooling gas and coal-fired power plants that produce most of the electricity — that only promises to get worse as temperatures rise further.

Next door to Syria, Iraq provides a case study. There, too, an authoritarian regime held together a disparate collection of communities through force until it could do so no longer. The means of its demise were far different, and, unlike Syria, the new Iraqi state has had the benefit of oil revenues to fund itself.

But forging a workable, effective governing arrangement between the various communities and constituencies has proven nearly impossible. That’s for many reasons, and the slow-but-steady worsening of climate conditions over the past quarter century is far from the most urgent of them.

Still, persistent droughts have all but rendered impossible the dreams of restoring, for example, the marvellous wetlands between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers that Saddam Hussein deliberately ruined during his brutal rule. Rising temperatures, now routinely reaching levels that test the limits of human survival in the south, have helped repeatedly overwhelm the country’s weak electrical grid.

One could argue that if the country got its act together investment would follow and these problems could be addressed. I would argue that getting its act together is also, increasingly, in a meaningful way, being hamstrung by the growing climate impacts. Yemen, for example, is a country now so crippled by environmental degradation, water shortages and institutional incapacity that the slow tide of climate-driven challenges may be too much to ever overcome.

Is dealing with the fallout of climate change the most urgent, pressing challenge for Iraq? Or Syria? No. But it will never be that — for any country, really, as this interesting theoretical card game demonstrates. Other challenges will always top the priority list. A United Nations conference on addressing global drought recently ended with nary a mention of climate change, indisputably one of the drivers of growing desertification across the planet. That means the root causes of the problem may remain largely unaddressed in favor localized adaptations and mitigations.

For Syria’s new government — assuming we get one, and whatever it consists of — that means the undertow of climate change will continue to tug at its attempts at progress, to pick away at the foundations of its authority, to hamper its ability to deliver and ultimately bring peace and stability to its piece of a troubled region.

And if the wider challenge of addressing climate change is not met by the rest of the world — particularly the world’s major emitters of greenhouse gases — Syria will be far from the last troubled country that must add this rising tide to its already overwhelming troubles.