From Kyoto to Glasgow

If tensions are rising between rich and poor, developed and developing nations, a COP can’t be far off….

So the news first: the devastating wave of Covid infections in India has forced me to delay my reporting until next spring. The ferocity of the epidemic has traumatized India. While infections and deaths are now falling, months more will be needed for life to return to normal. A third wave could hit before enough Indians are vaccinated to prevent another round of devastation. It’s not the right time to travel India exploring climate and energy, as critical as those issues remain.

I now plan to travel to India around May of next year to experience for myself the full panoply of climate impacts, from stronger cyclones (of which India has endured three so far this year), heat waves, disrupted monsoons, rising sea levels and melting glaciers. And to assess where the Covid cataclysm has left India’s economy and energy transition.

In the meantime, I’ll keep posting here, broadening the scope to examine climate and energy a bit more globally. Most of these ramblings will touch on India, underscoring its centrality to the world’s efforts to dramatically step up decarbonization of the energy system and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

A good place to start with this wider lens is international climate diplomacy, which is driving towards a critical inflection point this November. This is when delegates from around the world gather in Glasgow, Scotland to hold what is known in climate diplo-speak as the Conference of the Parties. The 26th meeting since 1995, Glasgow is thus dubbed COP26. The conferees, one from each country, are the top decision-makers in a United Nations-sponsored diplomatic process known as — warning: more incoming climate diplo-speak! — the UNFCCC.

That would be the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The UNFCCC’s COP talk-shop (and if you got through that alphabet soup, congratulations, you’ve successfully completed Climate Diplomacy Acronyms, 101) has wound its way through nearly three decades of meetings in 25 cities, from Berlin all the way around the world and back to Madrid, without slowing the build-up of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, much less reversing it.

However, the peripatetic gathering — think of a UN version of a Grateful Dead tour —had a remarkable kumbaya moment of clarity at COP21 back in 2015. This resulted in what’s known to UNFCCC non-initiates as the Paris Accords.

More on those below. But suffice it to say that Glasgow will be the first huge test of the feel-good, we’re-all-in-this-together-and-must-each-do-our-part spirit that pervaded a sprawling conference center on the outskirts of Paris that year, just weeks after the shocking massacre by ISIS gunmen of 130 young nightclub and concert goers and Parisien cafe diners.

With scenes like the memorial vigil pictured above that I attended and photographed unfolding around the city, French President Francois Hollande was able to toast a stunning global consensus forged in the final hours of the 12-day meeting: the moment for concerted action was now, and here’s how we’ll do it.

That didn’t reverse greenhouse gas emissions, either.

But it was, we can still hope, a start. Every country — even the United States — officially agreed there is a huge climate problem, that it is caused by man-made emissions of gasses and that each and every country had to do…something…of its own choosing…even if all those somethings added up wouldn’t be nearly enough to really solve the problem.

Like I said, a start, we can hope.

Glasgow is where the rubber hits the road — before it’s truly, honestly-this-time, no kidding, we-really-mean-it too late. Greenhouse gas levels are fast approaching alarming levels and climate warming is demonstrably, measurably gaining momentum. Countries, particularly the biggest greenhouse gas emitters, must scale their “somethings” up — drastically — so the sum of the efforts results in actual, real emissions cuts leading within a generation or less to the stabilization of greenhouse gas levels in the atmosphere.

These efforts — for those craving another dollop of diplo-speak, they are Nationally Determined Contributions, or NDCs — will need to be measured and accounted for in easy-to-compare ways so that everyone, everywhere can assess how we’re doing overall and as countries. We can then, soon enough, redouble these efforts yet again with confidence that every country is pulling its weight.

That’s what it will take, and more. This is what Glasgow is all about. And India plays a critical part.

Going into Glasgow, India now straddles a divide that has shaped global climate negotiations from the beginning: the chasm between rich, economically developed countries and poor developing ones.

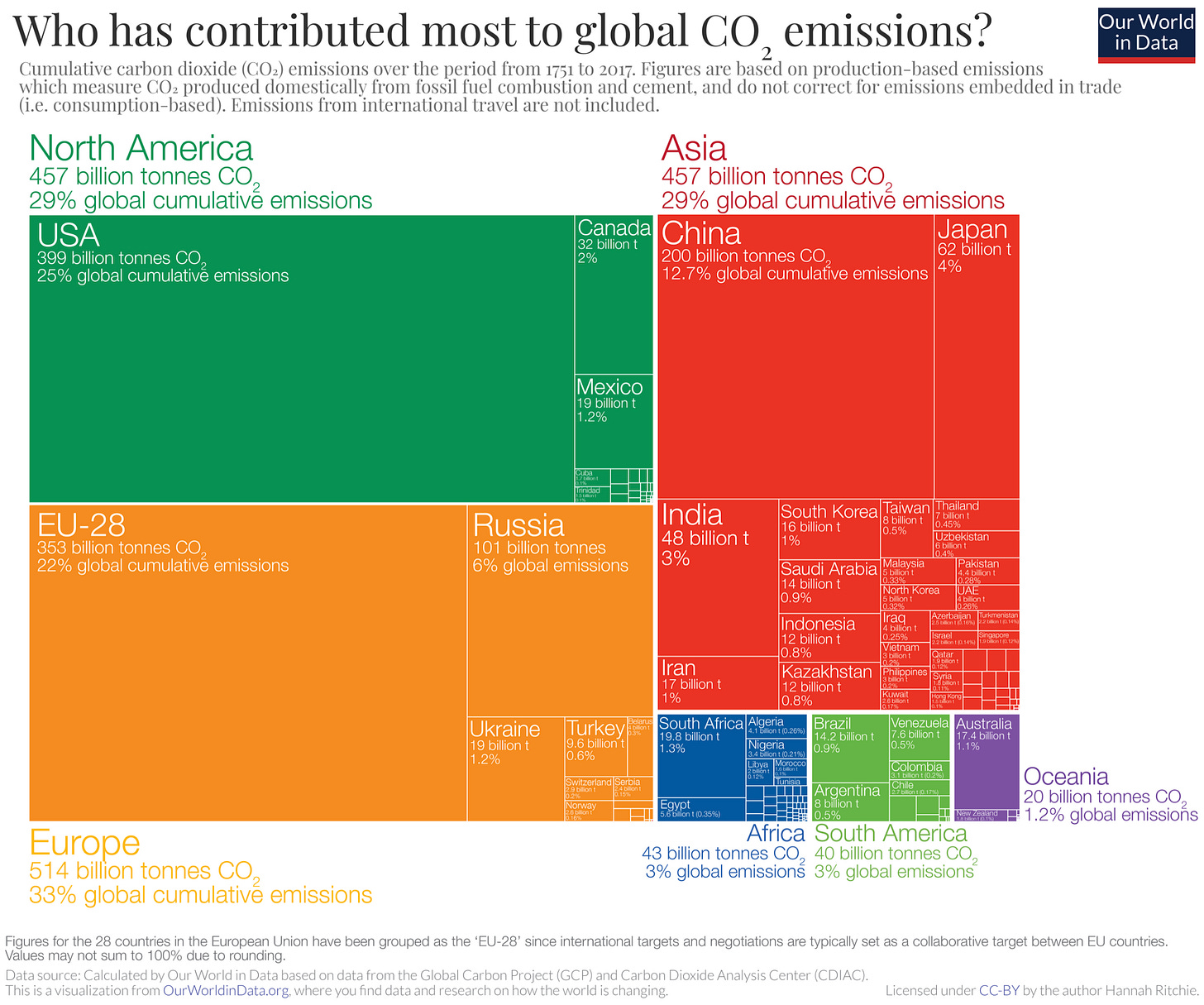

What’s not in dispute is that rich countries filled the atmosphere with carbon dioxide, methane and other greenhouse gasses as they went about getting rich, arguably knowing full well that’s what was happening for at least a generation. Also undisputed: However much rich nations take the rap for creating this mess, the problem can’t be solved without developing countries cutting emissions, too.

These two facts pitted developed and developing countries at odds from the beginning, way back at COP1 in Berlin 1995. Back then, the rich were the United States and Europe (including Britain!). The poor were many, but led by China and India with populous countries like Indonesia and Pakistan and the continent of Africa in tow. This group accounted for the vast bulk of humanity, and essentially none of its collective greenhouse gas emissions. Most of the people living in these countries didn’t have regular access to electricity or a motorcycle, much less a car. But their economies were beginning to grow, especially China’s, and their populations were younger than those in the developed world.

The first major global climate agreement, the Kyoto Protocol forged at COP3 in 1997, grudgingly settled on a formula imposing a schedule of greenhouse emissions cuts on the developed world while providing developing countries what was essentially a pass to pollute while they caught up. That’s fair, China and India argued, noting they had no intention of remaining poor and didn’t see any way to get wealthy without burning fossil fuels. Forget it, the U.S. Congress argued in rejecting the idea. No cuts from us unless China and the developing world also cut. The treaty was never signed by the U.S.

So the Kyoto protocol limped along without the biggest emitter on board. Developing countries fumed and remained intent on developing their economies, whatever the emissions. Greenhouse gas levels rose.

Fast forward two decades to Paris and much had changed. The underlying problem, man-made climate change, was worse of course, notwithstanding an endless debate in the U.S. over whether it even existed. China, however, while hardly “rich” after turning itself into the world’s factory floor on the back of coal-fired power, was looking more like a developed country by the day. It also was on the cusp of becoming the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitter.

Going into Paris, President Obama and Chinese leader Xi Jinping sealed a climate deal between their two countries that committed both to emissions cuts. The effect was to throw China squarely into the developed world camp. India, suddenly alone at the head of the developing countries, had just a few months earlier elected a new leader, Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

In Paris, Modi was keen to project India as an emerging global power in its own right. He decided to accept a new approach to solving the world’s climate problems. While India wouldn’t actually offer emissions cuts just yet, it would do…something….namely reduce the amount of greenhouse gases produced for each unit of additional economic growth….and more over time. Indeed, the implicit message India underscored was that every country could, and should, do something…as much as they felt they could. Progress was the point.

In the five-plus years since Paris much has changed again, not least the global ravages of the Covid pandemic. But even before that came some astonishing progress in the world of renewable energy: the price of wind and, especially, solar energy plummeted. It continues to fall, to the point where renewable energy is now often competitive with even the cheapest fossil fuels. That has taken the edge off some of the fighting over who should bear the burden of emissions cuts — since now, in theory, there is no burden, only cost savings, in taking up renewable energy.

The questions now turn more on who will assume the up-front costs of the energy transition — since even if renewables can pay off handsomely versus fossil fuels over the long haul, massive amounts of capital are still needed up front to build them. In practice, the new economics of renewables should make this problem easy to solve — afterall, modern finance is designed to price such risks and get the money flowing. And to a certain extent, efforts like this one by the Ikea and Rockefeller Foundations promise to “de-risk“ the construction of solar power in developing countries.

Yet the old tensions between developed and developing countries are creeping back, if they ever left. Developing countries, particularly India, are sore that upwards of $100 billion in funds promised to them by developing countries each year has failed to materialize so far. Developed countries point to unproductive investment climates that hold back those funds and much, much more in private investment.

The newest point of tension is over the developed world’s fetish with “Net Zero” commitments, the last of the climate lingo I’ll throw out there. Going into Glasgow, developed countries are announcing with great fanfare new promises to cut greenhouse gas emission to the point where the amount they spew into the atmosphere is at least equaled by the amount they pull from it (using everything from newly planted trees to advanced technologies that pull carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it, just like plants do).

Hence, net zero. The U.S. and Europe are aiming for the year 2050. China promises this by 2060. As many as 130 countries have either jumped on this bandwagon or are considering doing so. This is great, since of course global warming won’t stop until the levels of greenhouse gases stabilize, which means netting out at zero.

But as India, which has so far declined to make a net zero promise, points out: what really matters most is getting going on cuts sooner rather than later. That’s where big developed economies can make the biggest difference, since they’re emitting the most gasses right now. The developing world’s contribution comes later, the Indians point out, by avoiding future emissions even as they grow their energy consumption three or four fold in the coming generation.

In a reminder that the developing-developed world rift could complicate talks in Glasgow, India’s energy minister, R.K. Singh, recently dismissed the net zero promises as “pie in the sky,” arguing that by rights they ought to aim for “negative emissions”, not just net zero, to make up for their historic overindulgence.

Hard to see American leaders taking that challenge up any more than they were keen joining Kyoto way back when. Glasgow will be interesting.