As mentioned in my last post, I’m using the weeks before I arrive in India to lay out context for the reporting I’ll be featuring here over the coming months. We looked at India’s renewable energy future in the last post. This one digs into India’s coal-fueled past, present and, yes, future….

From Newcastle to Appalachia and well beyond, coal has woven its way into societies the world over. India is no exception.

These days Newcastle, among the world’s first coal capitals, has moved on from mining. Appalachia, home to America’s Piedmont coal belt, is deep in the throes of the industry’s decline.

In India, coal still provides close to three-quarters of the electrical power. India consumes more coal than any country except China (which, it’s worth noting, consumes a whole lot more). Coal India Ltd., the country’s primary producer, is the world’s largest. And even it doesn’t provide enough; India is also a huge coal importer. India — like China, Indonesia and Australia — sees a future for coal.

Not a forever future, to be sure. But, as India sees it, an indispensable, unavoidable, ongoing role for coal in growing the economy and lifting hundreds of millions out of poverty, beginning with energy poverty. India’s second-most-powerful politician made that clear recently. This doesn’t mean India is down on renewable energy — exactly the opposite, as we saw in the post that preceded this one. Graphs showing the expected rise of renewables in India, particularly solar, are impressive.

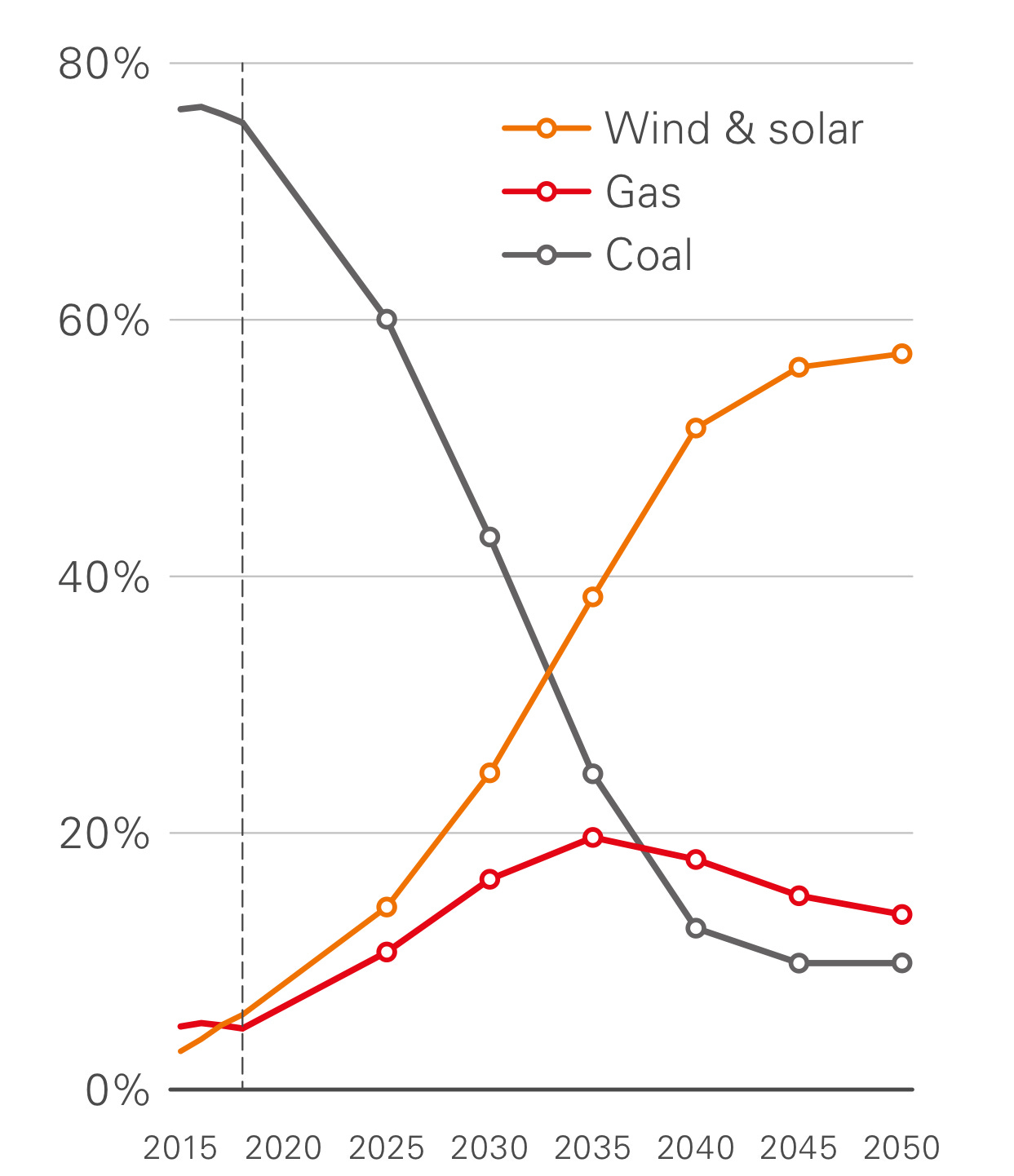

Here’s one from BP’s annual energy outlook last year, illustrating a theoretical scenario in which India moves “rapidly” in decarbonizing its electrical power generation:

Looks great. But those aiming for the early, or even eventual, decline of coal in India won’t find solace here: In this scenario coal generation increases by almost one-third over the next decade before declining to a globally very consequential 10% share of a much larger overall electricity system by 2050.

India’s most recent national electricity plan, released in 2018, lays out an even less dramatic change. Coal falls only to 48% of power generation by 2050. That would mean 60% more coal-powered generation three decades from now, since the plan pegs overall electricity demand growth at 4.5% annually.

What could kill coal off faster? Or, conversely, keep it going even longer? This is a conundrum I hope to get a much better feel for in the next few months. It’s at the heart of India’s energy transition challenge, and matters immensely to a world needing to be done with coal as soon as conceivably possible.

So, why can’t India be done with coal faster?

India’s coal dependence is hardly unusual, though coal’s path there reflects India’s unique history.

As Britain's premier colonial holding, India saw coal insinuate itself into the economy early in the industrial revolution. First coal-powered steam ships, then coal-powered locomotives arrived on India’s shores and moved inland to advance the business interests of the East India Company and the political interests of the British Raj that followed. From 1947, when India broke its colonial bonds, the newly independent nation leaned even more heavily upon coal in a massive industrialization push.

We’ve seen how renewable energy, particularly solar, is now pouring into India’s energy system. But if solar is less expensive than coal and growing so fast, why not less coal more quickly? For now, the answer’s simple: Solar is only cheapest when the sun is out. Coal-fired plants still must run a good deal of the time, especially when demand for electricity suddenly surges.

That dynamic may dissolve sooner than many Indian planners expect if battery storage costs fall rapidly — as indeed is happening. Then renewable energy could be profitably stored until after the sun sets.

This alone won’t make solar power easier to build, though. Prime, sunny land will get scarcer, and power grids will require expensive upgrades to take on more renewable electricity.

But these problems, too, will get solved over time.

That leaves the biggest challenge when it comes to coal (and not just for India): undoing the myriad ways coal has embedded itself across the economy, in politics, indeed throughout society. Unaddressed, this will slow coal’s demise even if phasing it out makes financial sense for India, and climate sense for everybody.

There are the directly affected — nearly 300,000 employees of Coal India. There are tens of thousands of the company’s pensioners, whose annuities derive not from invested assets but rather the company’s ongoing revenues. There are the many tens of thousands who work for Coal India contractors or mine coal informally for other smaller companies. Hundreds of thousands more livelihoods are supported by those coal wages as they course through the economy, the tea sellers and hair cutters and everyday goods and service providers in areas where coal is the economic mainstay.

Tough adjustments loom for governments, which receive large sums in taxes and dividend payments from coal use and production. The national railway earns more carting coal than any other kind of freight. That money, more than half the railway’s freight revenues, keeps passenger fares dirt cheap for 23 million daily rail riders. Each and every one of them is a voter in the world’s largest democracy, so raising passenger fares sharply is a non-starter.

These, of course, are India’s problems to solve. And it has strong incentives to do so. Topping of the list: improved air quality for hundreds of millions of its citizens currently being poisoned by particulate pollution. India’s cities have some of the worst air quality in the world.

But India will struggle to find the resources to simultaneously: a) build out its renewable energy capacity at breakneck speed and b) address the fallout as that eats into coal’s future. It can’t, and doesn’t, expect help with the latter task to come from beyond India. But the former, the build-out of one of the biggest energy infrastructures in the world, represents an opportunity unparalleled for the rest of the world to chip in and help.

By rights, that should already be happening. As part of the 2015 Paris Climate Accord, developed countries committed to pouring $100 billion annually for energy transition into developing economies like India by now. The money, disappointingly, has yet to materialize. Meanwhile, giant private investors, from Canadian pension funds to petro-state sovereign wealth funds, are eager to put hundreds of billions into Indian energy. But they’re hesitating from fully plunging in, concerned India’s complicated legal and investment landscape might trip them up.

If governments beyond India can’t ameliorate the fallout from India’s coal transition directly, surely they can find ways to deploy that $100 billion in service of improving the likelihood returns being realized. That could include everything from extending credit directly, to providing loan guarantees, to partnering with Indian and international investors. India, for its part, needs to step up by improving its ecosystem for foreign investment.

This is where Indian and international interests dovetail. The world is increasingly, urgently, concerned about the growing fallout from climate change. India is increasingly, urgently concerned about the growing fallout from climate change.

For good reason: India is among the countries expected to be most ravaged by climate change. I’ll take up just how challenging things look on that front in my next post, a week or so down the line.

The first line is so true: "From Newcastle to Appalachia and well beyond, coal has woven its way into societies the world over." As policymakers create more ambitious targets for emissions reductions, I hope they also planning for the livelihoods of the people in the coal industry. It is unlikely that solar installation jobs will cut it.

Excellent and comprehensive story Bill. I remember watching people gather the coal that fell off the trains at the side of the tracks - it will be a huge challenge to lessen its presence in India’s life and economy.