Coal Conundrum, Goan Style

Coal is the beating heart of India’s energy system. Few know this better than the residents of Goa, many of whom have had enough.

Most of our journey so far has been about the fallout from climate change and India’s renewable energy boom. But let’s not forget: coal remains the life-blood of India’s economy, despite being one of the country’s worst environmental scourges.

It courses through the subcontinent on railway cars and trucks, distributing black dust into the air, broken coal rubble along the way and ultimately carbon into the atmosphere when it is combusted to create heat and electricity. Domestic coal supplies are pulled from mines in the country’s east, deeply scarring the mined areas and communities there. Imported coal arrives on ships from Indonesia, Australia and South Africa, where similar environmental and community damage is inflicted, often by subsidiaries of Indian industrial conglomerates operating there. Coal is fuel for three-quarters of India’s total electricity generation. It generates all the heat used to make steel and cement. All these processes spew particulates and create huge accumulations of residual ash that add to India’s worst-in-the-world air pollution and widespread environmental degradation.

India is among the world’s most coal-dependent countries, relying on the dirtiest of all fossil fuels to meet fully 40% of its total energy demand, a share that’s risen over the past few decades, according to the International Energy Agency.

Few know all of this better than the residents of Goa. Though one of India’s smallest states, Goa’s gorgeous beaches and lush forests have made it a destination for everyone from 16th century Portuguese explorers to 1970s hippies. Into this coastline, which includes some of India’s largest sea-turtle nesting areas, is carved one of India’s biggest ports for off-loading coal from Australia and Indonesia. It is then carried on by rail through several seaside communities and across one of most biodiverse habitats in the world to steel mills further inland. Railway cars carry the rolled steel sheets back to the coast for transport around India and overseas.

Now the Indian government wants to vastly expand the port, put in another rail track parallel to the existing one and run a new electrical power line across the area.

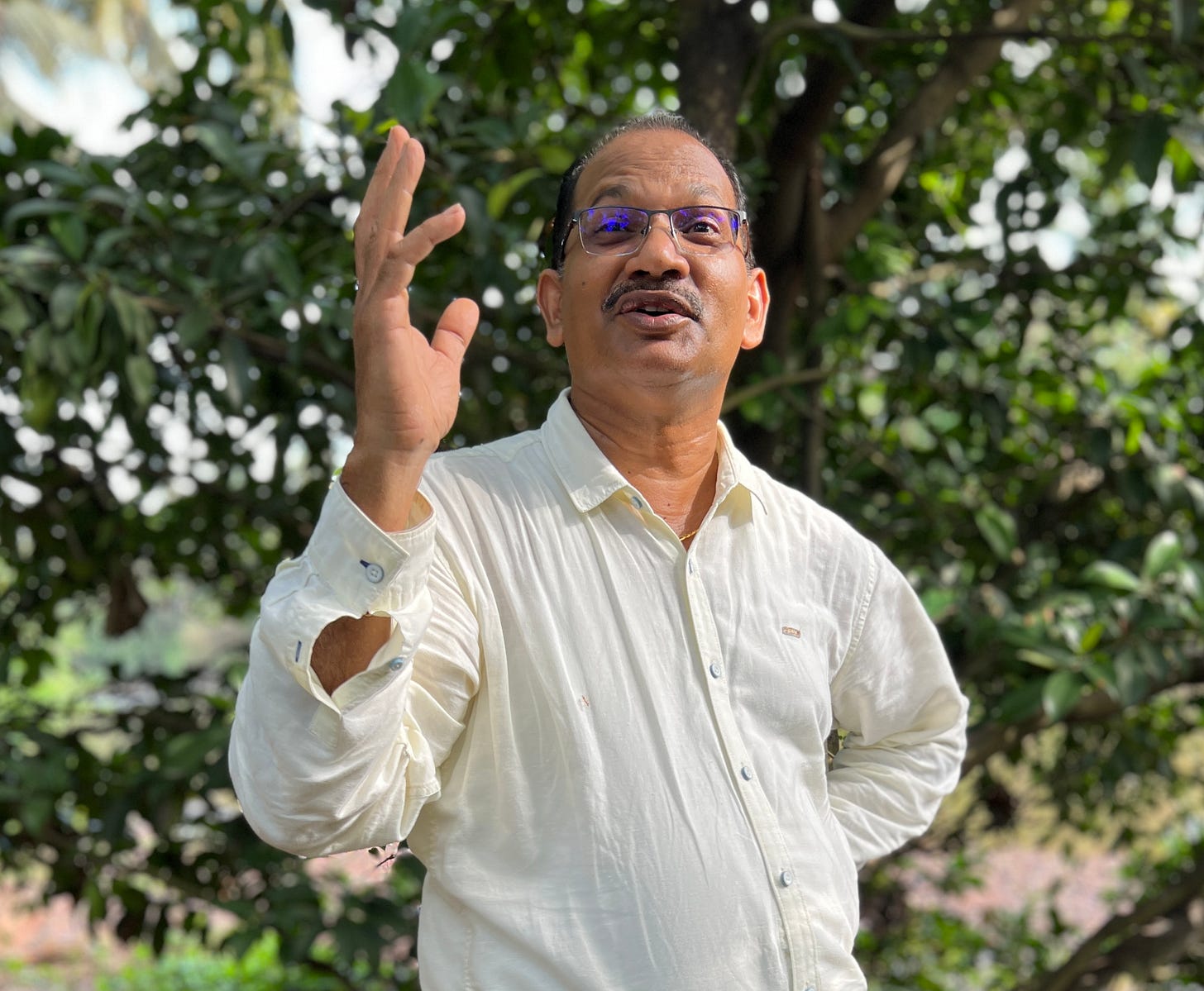

Orville Rodrigues is part of a citizens protest movement opposing the port expansion and trying to stop the doubling of the tracks, which requires a dramatic widening of the rail corridor through the center of a biodiversity reserve. Unlike the Konkan Railway, which parallels the coast and was the subject of my last post, this rail line is exclusively for freight. The first track already cuts through the mountain range known as the Western Ghats to reach the inland Deccan plateau in the state of Karnataka, home of huge steel mills owned by some in India’s richest and most powerful families. The port is operated by Gautam Adani, who has become Asia’s richest man since I wrote about him in this post a few years ago.

The movement, which has hamstrung the projects with marches and demonstrations, underscores the price India pays for its use of coal. Later in the journey we’ll look at the reverse: the cost to mining communities will pay when India begins moving away from coal. That day remains both inevitable and largely unplanned for. Such is the nature of dependence: destructive to continue, difficult to stop.

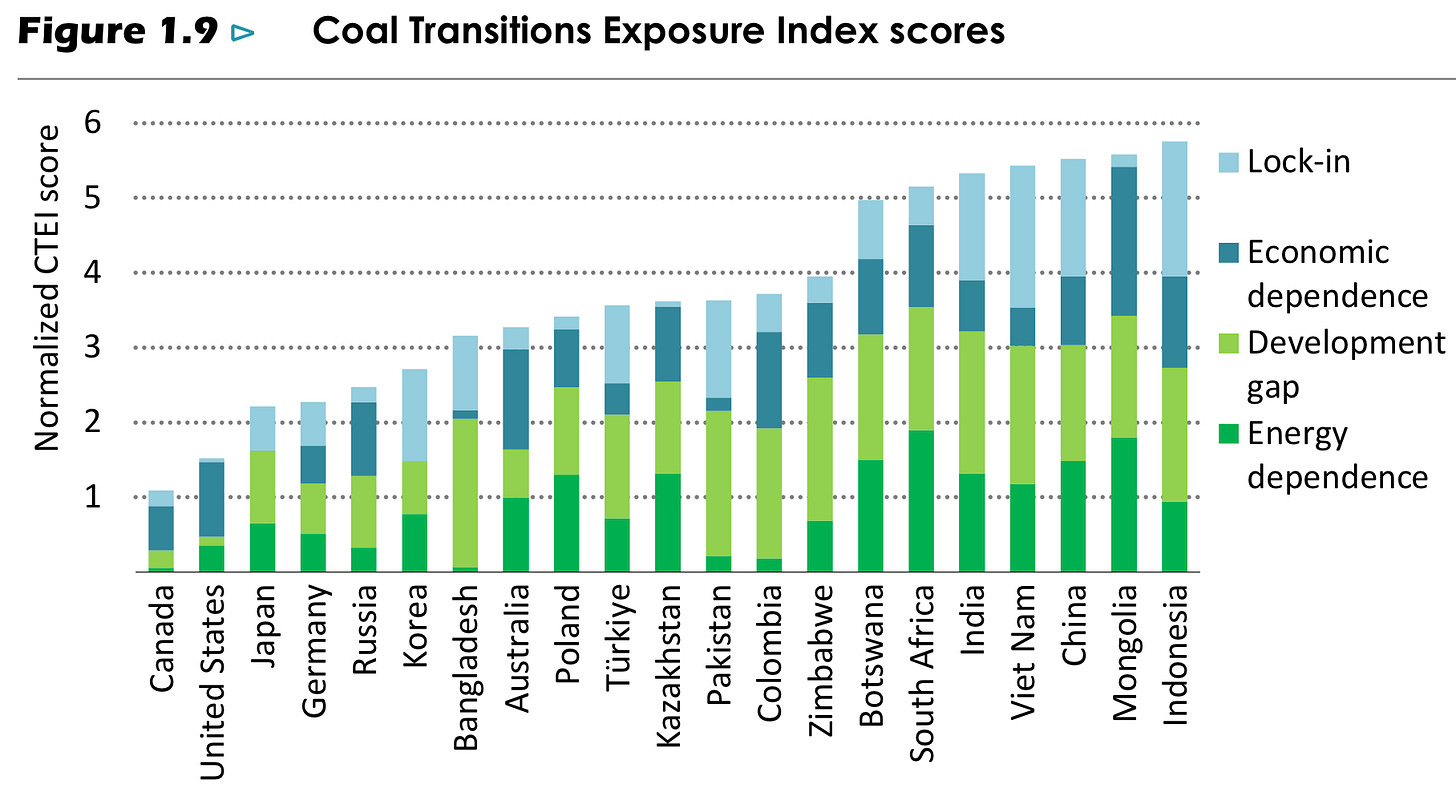

This chart (below) shows countries ranked by their various dependencies on coal, from the projected longevity of their steel and coal-fired power plants (“Lock-in”) to the share of coal in electricity generation (“Energy dependence”). “Development gap” represents the amount of economic growth per person needed to catch up with global averages — a gap likely to be addressed using their current, coal-based system. “Economic dependence” is the share of coal in total exports. As you can see, India exports very little coal, but its relatively young fleet of coal-fired power plants threatens to lock it into coal for longer as it struggles to meet energy demand that is expected to more than double over the next few decades.

Goa was a Portuguese colony from 1510 all the way to 1961, when the Indian government forcibly annexed the enclave a little over a dozen years after India threw off the British empire. Rodrigues hails from one of the many communities along the Arabian Sea coast that adopted Catholicism and developed a distinctly Goan Portuguese identity.

He brought me to see this home of one of his neighbors. The family claims the foundations date back even before explorer Vasco da Gama’s travels brought him to India in 1498. Today it retains the colonial era decor.

Rodrigues also showed me damage that the continuous rail trafficking of coal has caused the community. Despite plastic covers over the freight cars, coal dust from the jostling loads permeates the air and leaves a black film on foliage far from the tracks. Larger chunks of coal fall off and litter the sides of the railway bed. Many of the homes of residents are just a few feet from the tracks, which were cut and laid through land that was forcibly taken with only modest compensation. A doubling of the tracks would require the abandonment of many of the homes. These communities suffer elevated levels of respiratory disease, especially among children.

Residents and environmental activists also say the railway would severely damage the biodiversity reserve further inland with similar particulate pollution. It would also further bifurcate what was once a single, unimpeded natural habitat on both sides of the tracks. And the government is seeking to loosen regulations to permit more building and development, including piers, hotels and cruise ship berths, within a 500-meter band along the shoreline where all development is now prohibited.

The more they protest and resist, though, the more they’re accused by the government of selfishly standing in the way of national development, Rodrigues says.

“They tell the whole of India that we’re against the nation,” he says.

The protests in Goa began in April of 2020, just a few weeks after India’s leader, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, ordered one of the strictest national lockdowns in the world as Covid-19 cases began to appear in India.

The demonstrations were in response to India’s environmental ministry approving, in a video conference meeting, three large infrastructure projects — a second railroad track from the port, a four-lane doubling of a freeway and a second electrical transmission line alongside an existing one. All three projects cut through a major wildlife preserve in the Western Ghats mountain range, itself a United Nation’s World Heritage Site.

Despite the lockdown, a dynamic campaign against the projects gained momentum. Protestors blocked train tracks, with many eventually being arrested, including a well-known soccer star who got involved. The movement eventually was dubbed the Save Mollem campaign — on social media #SaveMollem — after the biodiversity reserve the trio of projects threatened. Youth leaders, who ran the gamut from naturalists to graphic designers, deployed art and music to great effect and drew national headlines. Well over 10,000 mask-wearing demonstrators turned out for some of the demonstrations, despite the Covid threat and in defiance of government restrictions on gatherings. The local Catholic church even provided support for the movement.

You can see some of the art works here. And this article has some terrific photos of the region’s natural beauty and unique collection of wildlife. Disha Shetty, one of India’s leading journalists covering environmental, climate and human rights issues, produced this series of stories on the movement with support from the Washington DC-based Pulitzer Center.

I spent a morning in Goa meeting with Sarita Fernandez, a coastal policy expert who has worked to protect the state’s Ridley Sea Turtle population and participated in the Save Mollem movement. She says the government likely didn’t realize what it was up against in Goa, a state with some of India’s highest levels of education and environmental awareness and a long history of defying the powers that be.

“Goans can get really rebellious and they did,” she told me.

So far, lawsuits filed by the movement have succeeded in halting or altering the projects on orders of the country’s special environmental courts. The government was told to drop the second electricity transmission line and string a new, higher capacity line on higher stanchions above the tree canopy in the forest to avoid having to cut through it. The road widening and railway track doubling were also rejected by the court for flaws in the environmental review, although the panel said the government could restart the project if a new environmental review showed a way to go forward without harming the natural surroundings.

Activists say that’s unrealistic, but the government hasn’t given up on the projects.