June 2, 2025

PUNTA ARENAS, Chile — Along the wind-battered Straits of Magellan in the far reaches of southern Chile, the final pieces of a unique demonstration project by Chilean energy company HIF were recently falling into place.

The project’s sole wind turbine was getting a tune up. An electrolyzer, a machine that uses electricity to separate hydrogen from water, was up and running. And workers were building the foundation for another machine, in transit from Germany, that would pull carbon dioxide from the air.

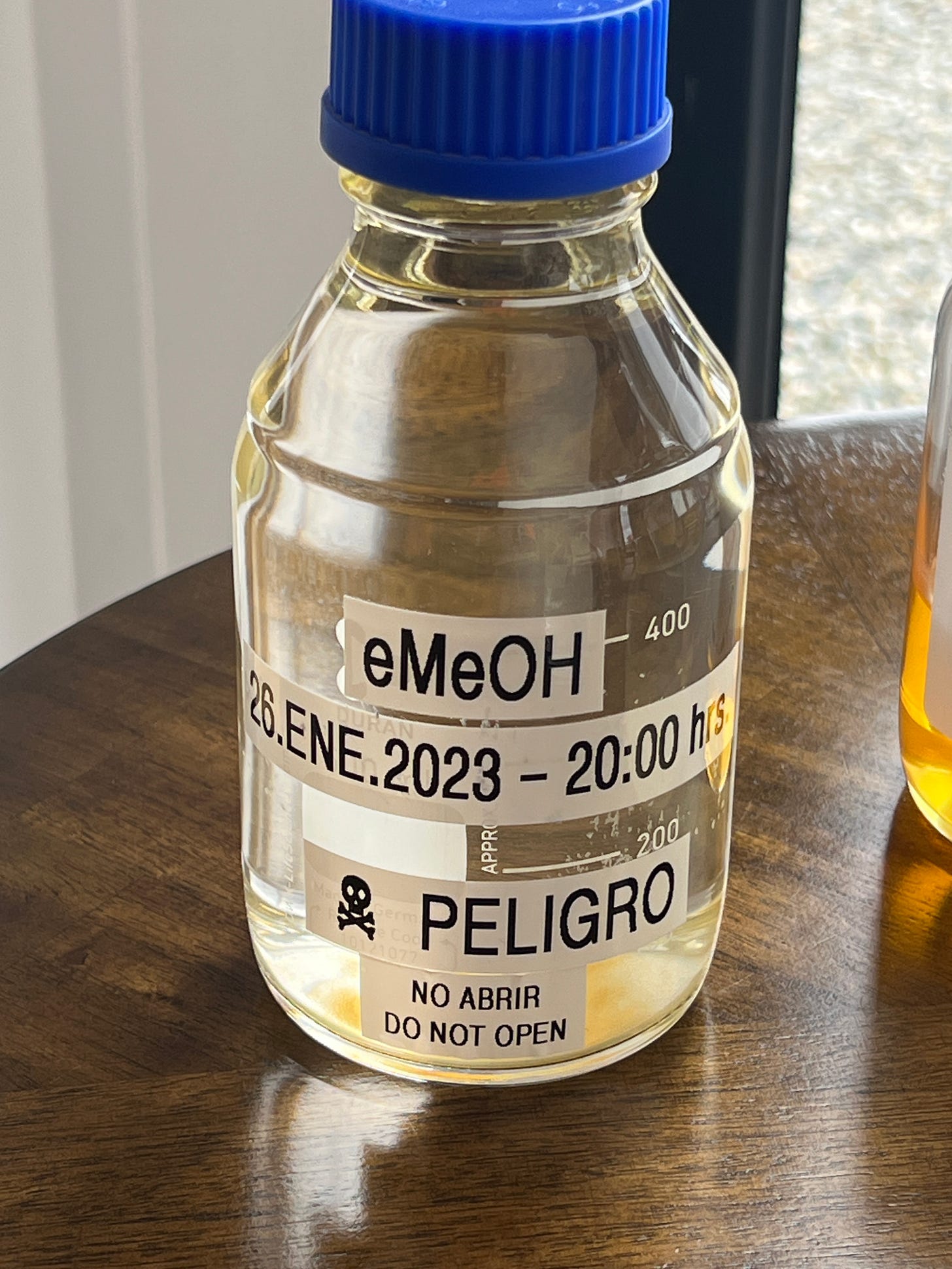

With this final piece in place, the plant, named Haru Oni in a local indigenous language, will demonstrate a way to scale up production of sustainable methanol and gasoline that can directly replace the emissions-heavy fossil fuels that power planes, boats and vehicles.

What’s needed now are committed customers — buyers willing to sign long-term contracts for future purchases of the fuels. Those promised purchases are critical in order for HIF to borrow the money it would need to build a full-scale plant a hundred times bigger than the demonstration plant.

“These are large-scale projects, so they have to have off-takers,” said Lee Beck, senior vice president for global policy and commercial strategy at HIF Global, referring to buyers for the fuels.

And therein lies the challenge, not only for HIF, but also for the clean hydrogen industry overall.

It’s a chicken-and-egg problem: Until costs fall, buyers are hesitant to commit to purchasing cleaner hydrogen, or fuels made from it. But without confirmed buyers, manufacturers are struggling to raise the funds necessary to increase production enough to reduce the cost.

Clean hydrogen, which is made using renewable energy or from natural gas with carbon capture, could be a key tool for reducing the carbon dioxide emissions that cause global warming, especially in industries for which reducing emissions is most challenging.

These industries include aviation, shipping, steelmaking, agriculture and refining petroleum products. Some countries, such as Japan and South Korea, plan to use clean hydrogen to reduce the emissions from fossil fuel-fired power plants.

But making clean hydrogen is expensive. And deploying it to make useful and transportable products such as gasoline, methanol, kerosene and ammonia makes the process even more costly. Depending on how and where the clean hydrogen is made, the price ranges from double to five times the cost of traditional hydrogen made with fossil fuels or other high-emitting processes currently in use, according to a slew of studies.

Those costs will fall as manufacturing processes improve and production volumes grow. But clean hydrogen might take a decade or more to become competitive — if it ever does, according to experts.

Plus, buyers aren’t sure what uses of clean hydrogen will work affordably and which ways of producing it will prove acceptable to governments and regulatory bodies that oversee international aviation and shipping.

“There are promising aspects, but so far nobody seems willing to pay for it,” said Jim Krane, a fellow at the Baker Institute for Public Policy at Rice University in Houston.

The governments of the United States, European Union, Japan and China have set up ambitious, and expensive, subsidy programs to try to jump-start the clean hydrogen industry.

Some of the biggest are incentives for clean hydrogen production passed by the Biden administration. The European Union has set targets for clean hydrogen use by 2030. Japan has a program to subsidize the difference in cost between clean hydrogen and hydrogen produced in ways that emit greenhouse gases.

But many of these efforts are faltering. The Trump administration — along with Republicans in Congress — have vowed to roll back many of Biden’s climate initiatives, though it remains unclear what exactly might be nixed.

European efforts are widely viewed as unachievable by the deadlines. And large-scale Japanese purchases depend on tricky technological breakthroughs.

These challenges have led to a raft of project cancellations around the globe as clean hydrogen looks too expensive for many of the potential uses that had generated excitement, such as for passenger cars and home heating.

Still, clean hydrogen could potentially help some industries, such as global aviation and shipping, meet growing clean-fuel requirements.

The EU, for example, requires all airlines to use 2% sustainable fuel this year, rising to 6% in 2030. Some U.S. states, including California, are discussing similar rules. The international body that regulates global shipping recently passed rules requiring a 4% reduction in carbon emissions from fuels by 2028 and 30% by 2035.

“They enable the development of many of the first movers that will be durable pieces of the clean hydrogen market, like sustainable aviation fuel, like e-methanol,” said Frank Wolak, president of the Fuel Cell and Hydrogen Energy Association in Washington, D.C.

For now, the clean hydrogen industry has mostly shifted to focus on these smaller niche applications. Producers have also moved toward less expensive ways of making clean hydrogen, such as by using natural gas with carbon capture to reduce emissions, or locating plants in places with exceedingly cheap renewable energy costs, such as Patagonia in Chile.

The local arm of French energy giant TotalEnergies recently applied to the Chilean government for permits to build a full-scale facility in Chile’s far south, for example. It aims to produce hydrogen using electricity from wind turbines and to use that hydrogen to make clean ammonia.

HIF has plans to build a commercial-scale plant in Matagorda, Texas that would make methanol for shipping and sustainable fuel for aviation by combining the clean hydrogen it makes together with CO2 purchased from other (likely highly subsidized) projects in Texas, as opposed to making its own CO2 on site, as Haru Oni is attempting to do. After lining up a large scale buyer for 100,000 metric tons of methanol annually, the project is moving forward to full production.

HIF’s Patagonia project — with German partners Porsche and Siemens Energy — is the company’s first effort to pair hydrogen production and carbon capture in the same facility, with both powered by the region’s legendary winds, blowing almost constantly. They can spin a turbine about 70% of the time, compared to around 30% for turbines in Germany, said Juan José Gana, the chief strategy officer for HIF Global.

“You need a place with stable electricity,” he said. But whether the project leads to full-scale commercial operation will depend on whether the price gets low enough to attract buyers.