A Railway and the Climate Challenge.

Few infrastructure projects have been built for climate more than the Konkan Railway. But does that prepare it for climate change?

What happens when a railway built for climate stress gets stressed further?

Earlier in our journey we saw how climate change is affecting India’s natural landscapes, such as the Sundarbans wetlands. We looked at the impact on agriculture in the tea fields of Darjeeling. Climate change will also take a huge toll on infrastructure, including the Indian railway — even, or perhaps especially, on infrastructure built to withstand environmental stress.

To my suprise, I found Indian railways officials largely unconcerned and mostly unresponsive to my queries about how climate change will affect the railway. Most of those I asked gave puzzled looks or launched into explanations of how the railway was rapidly electrifying its operations. The electrification of the railway is, indeed, impressive (if only half the solution, since nearly two-thirds of India’s electricity comes from burning coal).

But I was interested in more than how the railway is doing its part by cutting its carbon footprint. I also wanted to know how the railway — among the world’s largest pieces of infrastructure — will deal with the fallout from climate change: rising sea levels, stronger storms, more intense rains, and heat waves.

India is among the countries most vulnerable to climate change, which means equal risk for a railway that operates in every corner of the subcontinent and touches the lives of virtually every Indian. The railway employs some 1.5 million Indians, many of them working outdoors or in unairconditioned spaces. It transports over 20 million riders daily, most traveling in carriages without air conditioning. Surely lethal heat waves like the one India experienced when I was there would be top of mind. So, too, higher winds and more intense rain.

Somewhere within the sprawling railway bureaucracy someone must be contemplating how climate change will impact it. But I couldn’t find them. Instead, what I encountered were officials — virtually none of whom willing to talk on the record — trying day-to-day to keep up with climate challenges they’ve long confronted but increasingly worry could get much worse over time.

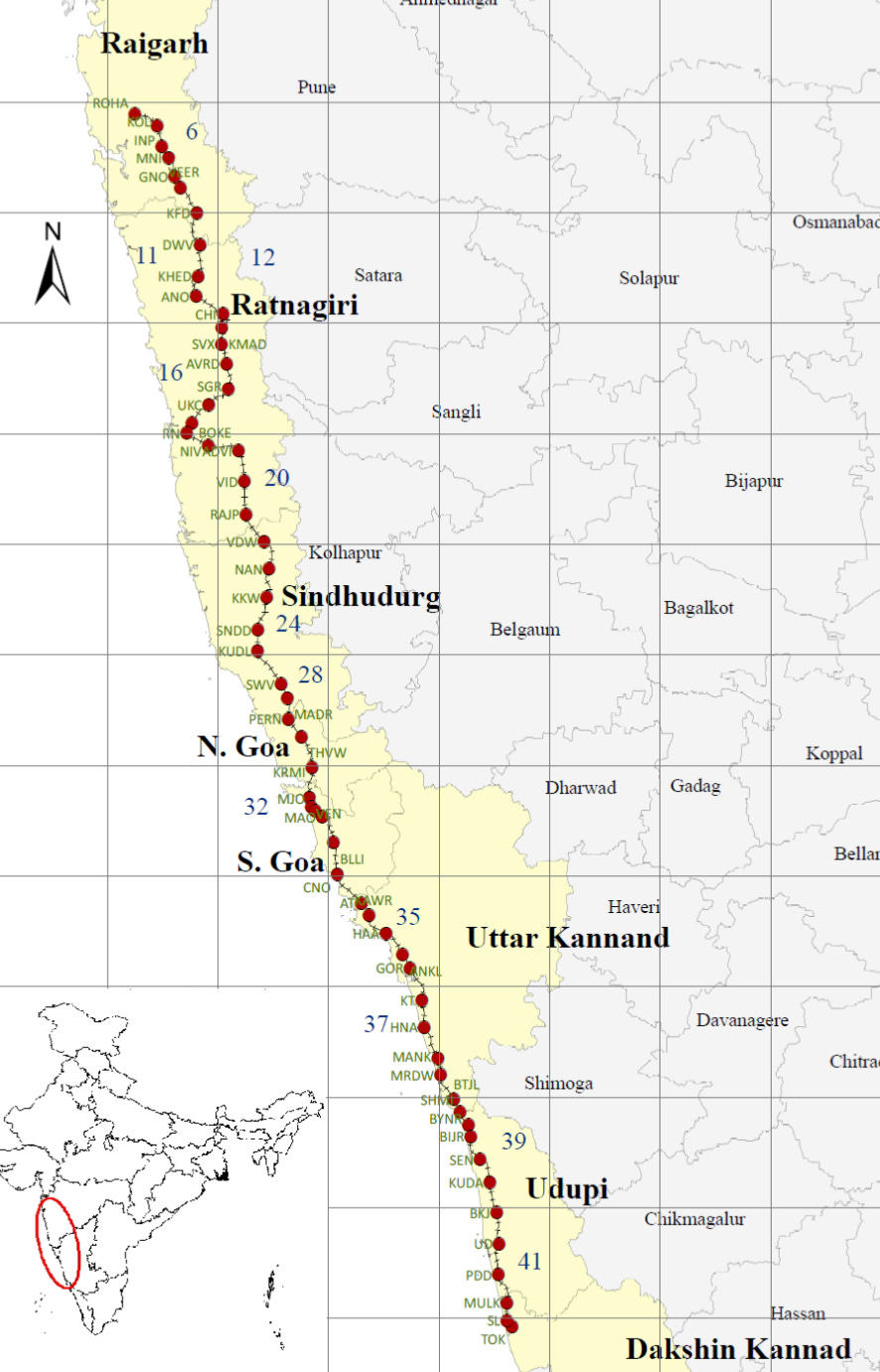

No place was that more evident than on the stunning stretch of track known as the Konkan Railway, which cuts a breathtakingly scenic path down the country’s Arabian Sea coastline along a mountain range known as the Western Ghats. This is a railway like no other in the world, with lush peaks to one side and blue seas on the other as it runs through the three states of Maharashtra, Goa and Karnataka.

Completed in 1998, the Konkan railway took just six years to build despite India’s one-time British colonial masters having dismissed a rail path through such challenging terrain as “not feasible.” The accomplishment was thus all the more gratifying for post-colonial India, and turned the man who honchoed the initiative — railway higher-up E. Sreedharan — into a legend. Sreedharan went on to build Delhi’s first-rate subway as an encore.

The 472 miles of Konkan rail line required more than 2,000 bridges and 93 tunnels, as well as sign-off (sometimes controversially) from some 42,000 landowners. Nine of the tunnels exceeded two kilometers, which was pretty much the longest previously built on the Indian railway. The longest of the Konkan tunnels was triple that.

But the challenges didn’t end with its completion. The Konkan Railway, which operates through some of India’s heaviest monsoon rains, suffered some horrible accidents during its first decade. A locomotive collided with a boulder that fell on the track in 2003 during heavy rain, leaving 51 passengers dead. The next year a landslide also deposited boulders on the tracks, causing the train that hit them to plunge into a ravine. Sixteen passengers died and 100 were injured.

Thousands of other landslides over the years have cost the railway months of lost operational time and millions in repairs.

So the managers of the Konkan Railway are hardly unfamiliar with environmental and weather challenges. Indeed, these are hardwired into the history and ongoing operations of the railway, literally defining its identity.

Yet climate change will bring new challenges, not so much in type as in intensity, according to a 2013 study by researchers at the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad. These challenges will manifest in two ways.

The first will be a steady step-up in the average temperature, with the resulting impact on weather distributed more or less evenly. Say, a half-degree warmer daily temperature average over the next decade yielding a quarter-inch more rain, but falling with roughly the same regularity across the monsoons over the next decade.

The second manifestation is more variability, with more torrential downpours interspersed with longer dry spells.

For now, that first manifestation is fairly benign, since the engineers who built the Konkan Railway included buffers to deal with the occasional deviation from the average. As long as weather deviations don’t exceed those buffers, the existing infrastructure and operations to maintain continue to perform. On the other hand, if those buffers — which, remember, were built with past weather patterns not future climate changes in mind — are eventually exceeded by new day-to-day weather parameters, well, then the railway is in serious trouble.

But the big worry is that the second scenario gets the upper hand, and weather extremes become, well, even more extreme. The evidence so far is this is what’s happening. The usual evenly distributed rains of the monsoon are more often bursting forth in the torrential downpours that loosen boulders and trigger landslides.

So far, railway officials are managing the challenges much as they have since the ugly accidents of 2003-2004: by building stepped grading along particularly vulnerable stretches of track, adding metal netting to hold the slopes and bolts to secure rock in place. They’re experimenting with automated landslide detectors, and have stepped up monitoring of the track, with local villagers deputized to walk every kilometer of track twice daily to report any signs of loose rock on or near the track.

Drivers have also been given more discretion to slow their locomotives during heavy downpours without regard to schedule disruptions, two railway officials told me.

All those measures may not be enough, as the study notes that one of the bigger factors holding rock in place is total forest cover in the areas nearby the track but beyond the railway’s control. Those areas are undergoing ever more intense development pressures, which almost invariably bring deforestation with them.

So far, the Konkan railway is holding out. There haven’t been any major accidents in recent years, after the railway management stepped up its efforts in the wake of the two accidents after the millenium turn. The two officials who spoke to me said they took comfort in the railway’s practice of building infrastructure to last 200 years.

The problem is that’s 200 years based on past weather patterns, and the next two centuries aren’t likely to look like the last two.